The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Stolen Millions in EU Funds – The Organised Crime and Corruption Watch, regional edition no1.

This is a collaborative bulletin researched by the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project’s seven investigative outlets: Investigace.cz (Czech Republic), Bird.bg (Bulgaria), Frontstory.pl (Poland), Rise Project (Romania), Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak – icjk.sk (Slovakia), Átlátszó (Hungary), Context Investigative Reporting Project (Romania). The team will explore an organized crime or corruption topic for each edition and showcase the most relevant facts. This is part one of a two part series on EU funds fraud.

Recent investigative reporting has shown multiple instances of EU fund fraud in multiple Eastern European countries. For instance Hungary invested €26 million in a state-of-the-art waste treatment facility that mysteriously caught fire. Átlátszó uncovered the story, and recently the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) opened an official investigation looking into potential financial crimes. In Slovakia, criminals defrauded millions from a €1.4 billion Covid relief fund. The EU funds should have helped local companies maintain operations during the pandemic but instead ended up in the bank accounts of secretive offshore companies. And in Romania, a €1 billion EU fund designated to the UNESCO-protected Danube Delta was defrauded by local, politically connected businesses.

Hungary

EU-funded projects in Hungary are regularly overpriced in a centralized manner – as the study “Corruption risk of EU funds in Hungary” by Transparency International Hungary (TI) established back in 2015. The study identified the various methods used to siphon EU funds from public procurement projects, often tailoring projects to give a specific bidder the ability to influence the selection process.

According to the EU anti-fraud agency’s 2021 yearly report, Hungary has the most recommendations in OLAF’s country list of EU fund recovery between 2017 and 2021. During those four years, OLAF concluded 26 probes into fund misuse and recommended EU Commission recover 0.69 percent of payments made to Hungary. However, local Hungarian prosecutors issued just four indictments on the misuse of EU funds.

Over many years, the Hungarian investigative center Atlatszo has uncovered massive corruption in EU-funded projects. Atlatszo was the first to report on the Elios case involving István Tiborcz, the prime minister’s son-in-law. In this scandal, Elios Zrt, the company co-owned by Tiborcz, was awarded tens of millions of euros to upgrade street lights all over Hungary.

Atlatszo concluded that the majority of the tenders Elios Zrt won would not pass tests conducted by OLAF, the EU’s anti-fraud office. Later, OLAF confirmed those conclusions in an official report. However, the Hungarian investigative authority and prosecutor’s office sabotaged the Elios investigation and Hungarian taxpayers ended up paying the bill instead of the Tiborczs.

This is just one of many cases first reported by media outlets and investigative journalists before evolving into OLAF investigations and national criminal cases. Sentences are sometimes handed out secretly: as Atlatszo found out in 2022, a Hungarian billionaire was quietly sentenced by a court in an EU tender fraud case, without any news published about the case or the verdict.

The Hungarian government decided not to participate in establishing the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) in 2021. A year later, in 2022, the European Commission announced its intention to freeze more than 7 billion in economic development funds for Hungary over its failures to tackle corruption. The Commission announced that Hungary must meet essential milestones to access Recovery and Resilience funds and implement measures to combat corruption, including setting up an Integrity Authority and an Anti-Corruption Task Force. Meanwhile, the Hungarian Ministry of Interior official website states that “Hungary, according to national, European and international surveys, is moderately affected by corruption.”

‘Anything that can go wrong will go wrong’ – A project that complies with all Murphy’s Law but not with EU law

In November 2022, the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) announced discovering fund mismanagement in an EU-financed Hungarian waste management project. OLAF recommended the EU claw back €11 million from Hungary for the failed project.

This follows a 2019, of the waste management project, uncovering the root of the problem. The investigation started after locals near Lake Balaton, in Királyszentistván, complained about air pollution resulting from a landfill catching on fire three times in a year. These fires covered the area with thick black smoke, soot, and ash.

The landfill in Királyszentistván was established as part of a €26 million EU development project. Granted in 2003, it was supposed to collect, and properly treat, household waste from 158 towns and villages. The critical element was constructing a regional waste treatment plant in Királyszentistván.

A legal battle prompted by local environmental NGOs, who were against the construction of the waste treatment plant, delayed the project. A major concern was the planned location of the plant was in a sensitive groundwater quality protection area. In 2008, they lost the court battles, and the construction started.

In April 2011, following construction of the plant, the three-month trial undertaken by the public engineering consortium ended. However, two days before the official handover in May, a mysterious fire burned down the brand-new biological-mechanical treatment hall.

The case was settled among the participants — the constructing consortium and the municipal waste management association — without court involvement. The consortium agreed to pay 60% of the estimated damages to fund repairs. How the amount was determined, who was responsible for the fire, and under what circumstances it started remain unclear. The building repair took two years, further delaying the project deadline beyond its original deadline.

Critically, this impacted the required organic waste separation and treatment that should have taken place in the biological-mechanical hall. Thus, most organic waste went into a landfill, contrary to the original project plans and EU waste policy.

Within a year, nearby residents began complaining of horrible smells. In 2017, experts proved the source of the stench was clearly the Királyszentistván facility, primarily the depot (the area where the waste is finally dumped), the leachate reservoir, and the biological hall (where the biological waste is loaded and treated). The stench could be smelled from a distance of 3-5 km on several occasions.

Investigations revealed the treatment hall machines had broken for several years, hampering the sorting and mechanical handling of organic waste. Additionally, even though recoverable fuel materials, such as wood, was properly sorted and treated, it was not transported away for use. Instead, its owner left the materials on site where it was often dumped in the landfill. And in 2019 the fuel materials even caught fire.

As a result of public outcry over the stench, biological waste was not treated in the Királyszentistván facility between 2018 and 2021 but was transferred to another landfill.

During those years, the municipal waste association won three other large EU development grants, receiving approximately €20 million (calculated at today’s exchange rate) on top of the initial €26 million grant in 2003. All three projects aimed to develop the waste management system further; still, the Királyszentistván facility provided very poor performance throughout these years, as described above.

In response to Átlátszó’s questions, the organization operating the North Balaton system confirmed that OLAF had investigated them. However, they denied the legitimacy of OLAF’s allegations.

Romania

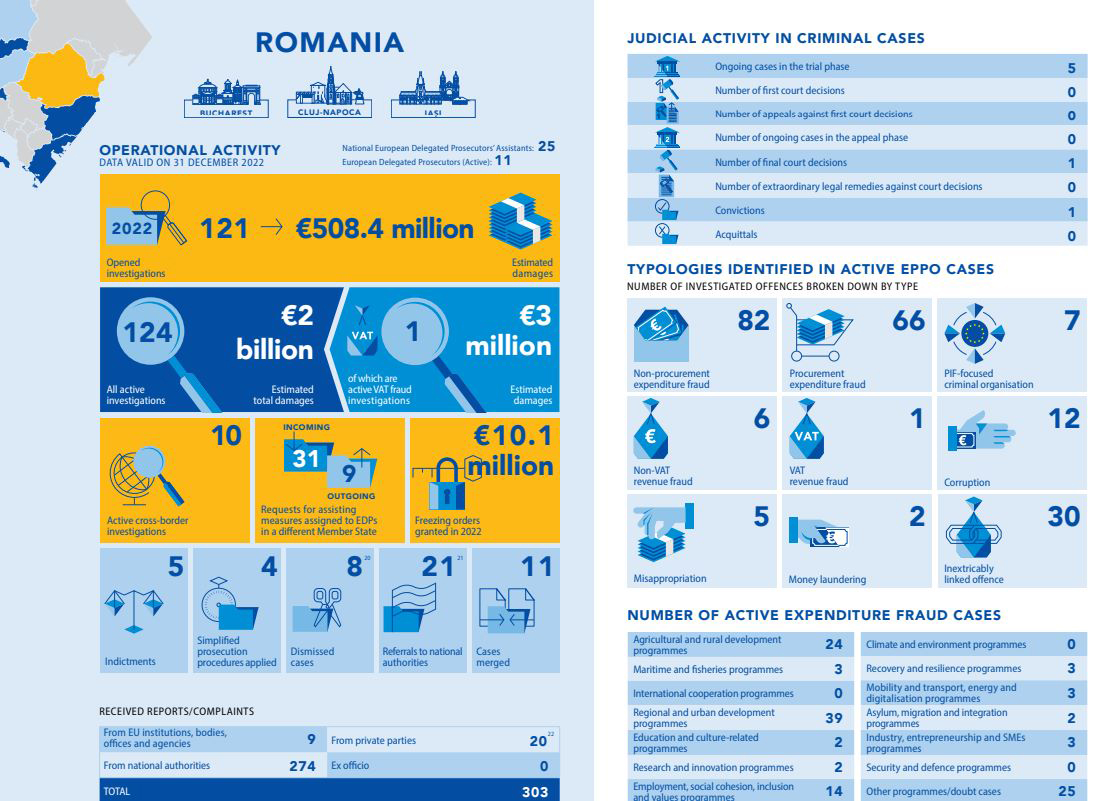

Romania has a long track record of defrauding EU funds, proven by criminal and journalistic investigations. A 2021 European Public Prosecutors Office (EPPO) report noted Romania is just behind Italy in the suspected amounts criminally defrauded. “We have hundreds of files registered at EPPO Romania,” said Laura Kovesi, the head of the EPPO in an interview for Context.ro. According to Kovesi, one of the biggest criminal cases investigated by her team is related to EU funds designated for the Danube Delta. This criminal case started after the Romanian investigative outlet InfoSudEst.ro and Süddeutsche Zeitung exposed that a group of politically connected businessmen defrauded at least €100 million from a total of €1 billion. The fund should have been invested in the local community but never reached the shores of the Danube Delta.

Last year the EPPO reported 44 active investigations that accounted to a total of €1.3 billion in damages. Some of the cases it investigated had cross-border components, and Kovesi believes organized crime groups are very active in the EU. “I noticed the great flexibility of these organized groups, the ways of communication between them are very simple and clear,” she said. Kovesi notes the biggest enforcement problem is just being able to detect these criminal groups’ involvement.

One recent example is an Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) investigation published last year about the heist of a €20 million EU-funded grant designated to feed the most vulnerable Romanian citizens. The funds were allegedly stolen by members of two organized crime groups: one based in Bulgaria and one based in Romania. The cross-border investigation by Rise Project and Bivol showed how the stolen fund ended up in Bulgarian luxury purchases and real estate.

The bribe is 50% of the contracts

Fraud is on the European Commission’s radar, and a 2021 report has Romania at the top of the list of countries where EU funds are defrauded. The 2020 report noted 237 irregularities covering more than €166 million of EU grants. A recent OLAF report also identified Romania as one of the countries more prone to fraud, showcasing that two of the most vicious frauds it investigated involved Romania.

OLAF reports are sometimes referred to the Romanian National Department of Anticorruption (NDA). According to a 2022 NDA report, the number of criminal fraud cases is high with the department registering 590 new cases concerning EU funds at an estimated value of €25 million. Bribes are a common component of these cases, sometimes with “the bribe negotiated as a percentage was of up to 50% of the amount obtained.”

Slovakia

Slovakia has been an EU budget net beneficiary since it joined the bloc in 2004. In the 2021-2027 multiannual financial framework, €12.8 billion is allocated for Slovakia. At the same time, it is a country among the worst at spending EU funds. It failed to spend some €6 billion from the previous financial framework.

And of what it spends, the money often goes to projects showing the highest number of “irregularities”. For many years, Annual OLAF reports show the highest detection rates of irregularities and their financial impact in European Structural and Investment Funds and agriculture. In 2020, 15.41% of payments on Slovak projects showed “irregularities”. This is the highest number within the EU; second is Romania with 8.03%, and third, Greece at 1.97%. However, there has been progress — Slovakian irregularities was 21.03% in 2019.

It is important to note this does not mean a fifth of all projects in Slovakia are corrupt. In the past, this high number was explained by Slovak controllers as a sign that they have the most robust system of reporting irregularities that they have the most robust system of reporting irregularities. But the idea that EU funds are a breeding ground for corruption is widespread in the Slovak public. The idea that everyone must pay a standard 20% bribe to have EU fund applications approved is an urban legend. However, that perception is reinforced with every EU fund corruption case that surfaces — cases that continue to increase and sometime reach the highest echelons of Slovak society.

The country in which Cattle Farmers hold the Golden Key to the EU-funded cake

In October 2021, the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak (ICJK) reported on how €24 million ended up in the accounts of shell companies. The story revealed that Slovak shell companies were used to steal EU funds.

The scheme started during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Slovak government decided to set up an emergency €1.3 billion fund called “First Aid” backed with money from the European Regional Development Fund.

As advertised by the government, the “First Aid” program was designed to rapidly provide financial aid to businesses struggling because of the state-imposed pandemic restrictions. Businesses could receive money to help pay rent or their employees. This allowed them to receive hundreds of thousands or even millions of euros to prevent them from having to fire employees during the pandemic.

The ICJK identified multiple companies that received millions in aid, even though they had no employees, did not file financial statements or annual accounts, and their owners were all foreign citizens. Later research by the ICJK revealed these “owners” were fictional with names most likely to have just been made up.

By fall 2022, the police and prosecutors have charged not only Bureau of Labour employees who approved the payments to these companies, but also several members of an organized criminal group, including two of its supposed leaders. Reportedly, much of the identified payments have been halted, but the estimated cost to the state (and the EU by extension) reached over €13.7 million.

€10 Million Bribes in Cattle Farmer Scheme

Ever since 2018, when the murder of Slovakian investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancee Martina Kušnírová rocked the country and the political landscape, it is not only these small-scale and regional cases generating public outcry and judicial interest.

In March 2020, the National Crime Agency (NAKA) began an investigation codenamed “Dobytkár” (Cattle Farmer). In its scope, it is one of Slovak’s largest corruption cases. NAKA claims some applicants for funding from the EU Common Agricultural Policy were forced to pay bribes to receive payments. This supposedly was not just a number of individual cases; it was systematic corruption. And according to the investigators, at least €10 million were paid in bribes.

In the “Dobytkár” case, 19 persons were charged. Among them were high-ranking bureaucrats, such as former Agricultural Paying Agency (APA) leaders Juraj Kožuch and Ľubomír Partika, and well-known oligarchs Martin Kvietik and Norbert Bödör. The latter is known for his associations with the political party of Robert Fico, SMER-SD, which was in power from 2006-2010 and 2012-2020.

In 2014 and 2015, Robert Fico gave a speech in the regional city Nitra, at a party hosted by Bonul, a private security company owned by Norbert Bödör. Notably, during those years Bonul had won many public tenders. After his speech, the then-prime minister did not go back to Bratislava but rather to the hotel “Zlatý kľúčik” (Golden key), which was for years known as one of the favorite venues of SMER-SD politicians.

It was the later murdered investigative journalist Ján Kuciak, who in 2017 proved Zlatý Kľúčik was owned by Norbert Bödör, even though on paper it was owned by two unknown companies. It was revealed that these two companies received tens of millions of euros from the APA, including €2.4 million in 2016, to buy and renovate the hotel Zlatý kľúčik. A grant that was, as Kuciak wrote, unwarranted given the EU fund requirements, but still approved by the APA chief Partika.

Norbert Bödör was indicted in the Dobytkár case. The trial started in February 202 and continues today. However, Bödör is not the only oligarch now facing trouble. Jozef Brhel, also allegedly one of the “sponsors” of the SMER-SD party.

As ICJK unveiled in 2021, several of Brhel’s companies were granted lucrative licenses to build solar power plants in 2009, and at least three of them built them with €11.4 million euros from EU Structural Funds grants. He is currently indicted and under trial in another case, “Mýtnik” (Toll-collector), for corruption and money laundering related to these projects.

We are still waiting for the start of the trial in the “First Aid” case. And just a few months after ICJK broke this story, it broke another one, in which a different set of companies received “First Aid” grants worth €700,000 to cover their rent expenses. That money was supposed to help businesses required to pay rent despite being closed due to the pandemic. The companies ICJK wrote about received subsidies even though the premises were closed prior to the pandemic. Unlike the employment scheme described earlier, authorities are not investigating this case.

This shows there remains an appetite in Slovakia to have a share of the cake, particularly EU-funded cake. With the 2021-2027 EU multiannual financial framework containing €12.8 billion for Slovakia, and with the additional €6.3 billion allocated for the Slovak recovery and resilience plan, the opportunities and incentives for fraud keep getting bigger. It is up to national policing, and independent media, to continue uncovering these fraudulent schemes to ensure these funds are spent properly.

The list of corruption scandals connected with EU funds over the years is long and exhausting. In the last several years, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO) has taken over more and more of these cases. For 2021, it reports 42 active investigations, mostly connected to VAT frauds, but some of them “…concern either corruption in the allocation of European funds or the actual use of European funds,” according to European prosecutor Juraj Novocký.

In May 2022, the EPPO filed the first charge in Slovakia. Three persons were indicted for creating an organized group that defrauded the European Regional Development Fund of €375,000.

In November 2020, a regional case surfaced. A businessman with a job placement project claims he was approached by a regional member of the Slovakian Parliament who also sits on the commission deciding on EU-funded projects and asked for a bribe. Another businessman explained that from the approved sum, he only gets 80 percent. This again confirms widespread suspicions about a fixed 20% “rate” of bribes.

Tamás Bodoky – Atlatszo (Hungary), Orsolya Fülöp – Atlatszo (Hungary), Bianca Albu – Rise Project (Romania), Attila Biro – Context Investigative Reporting Project (Romania), Tomáš Madleňák – Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak (Slovakia)

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!