The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Is high inflation in Hungary really caused by the war in Ukraine?

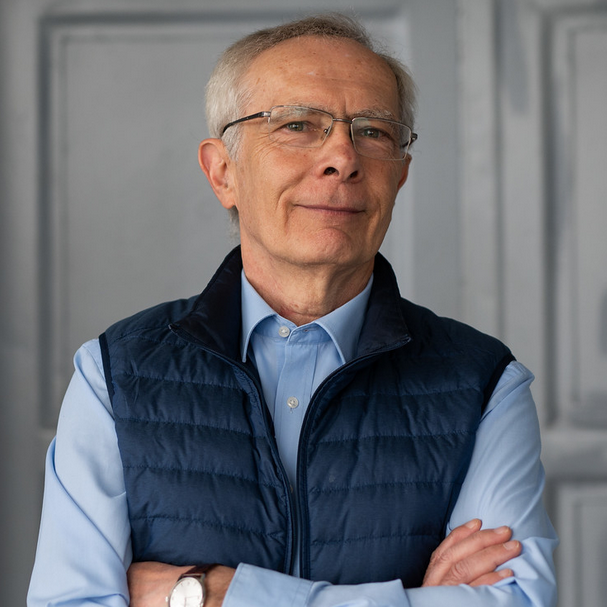

Consumer prices in Hungary were 16 percent higher in August than a year earlier, as the Hungarian government continues to talk of wartime inflation. Can we actually talk about wartime inflation in Hungary? What has caused consumer prices to soar globally? What are the inflation expectations for next year? These are the questions that Péter Ákos Bod, Hungarian economist, university professor and former Governor of the National Bank of Hungary, helped us answer.

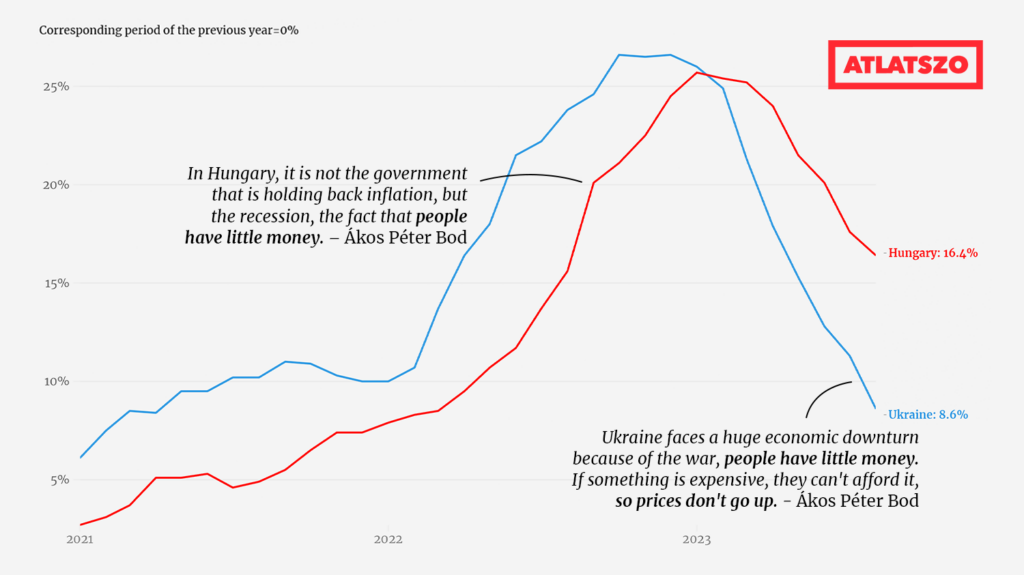

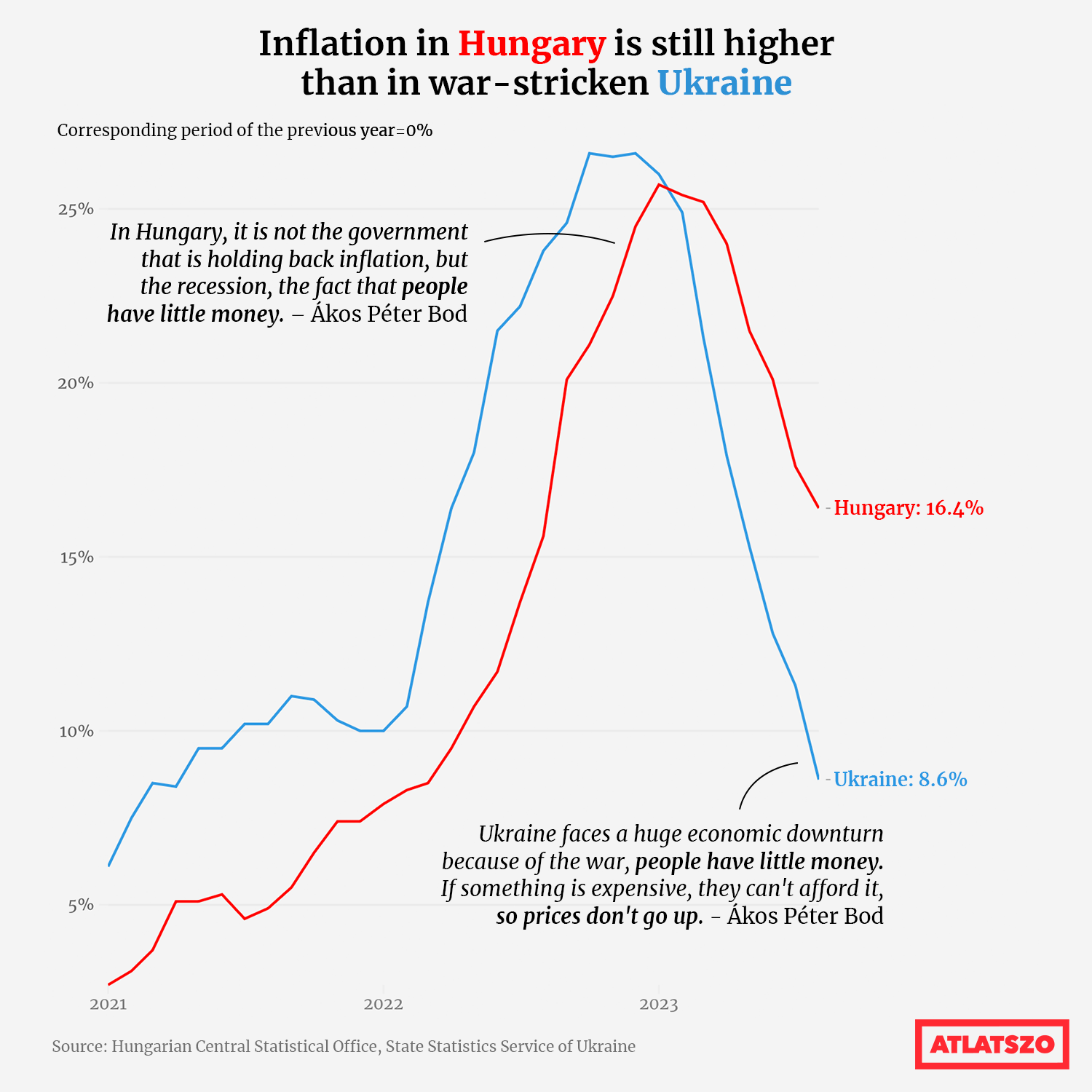

According to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH), consumer price inflation was 16.4% year-on-year in August. Following our last summary, we now look at inflation in Ukraine, in addition to the EU comparison, and examine whether we can talk about ‘wartime inflation’ in Hungary.

Starting to catch up

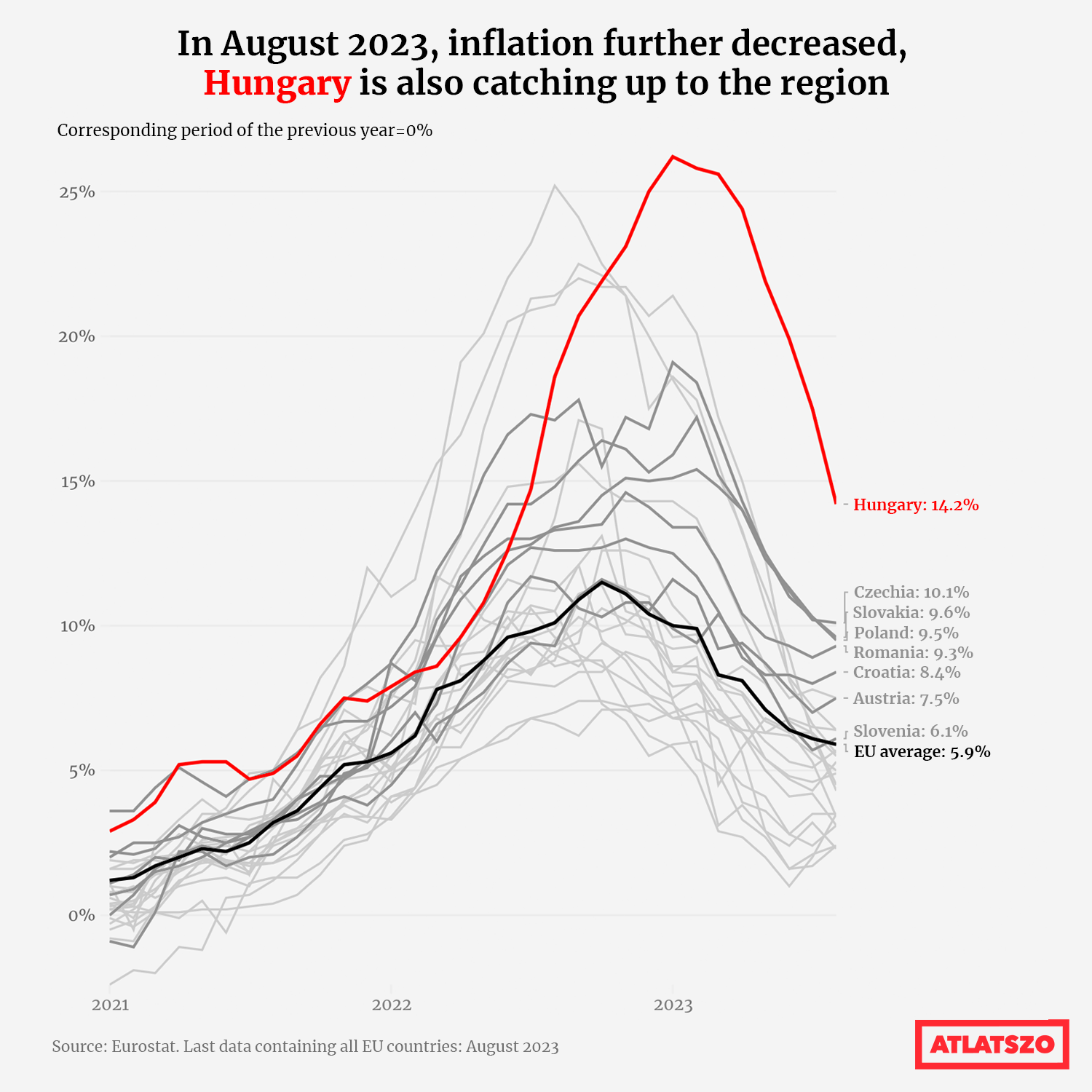

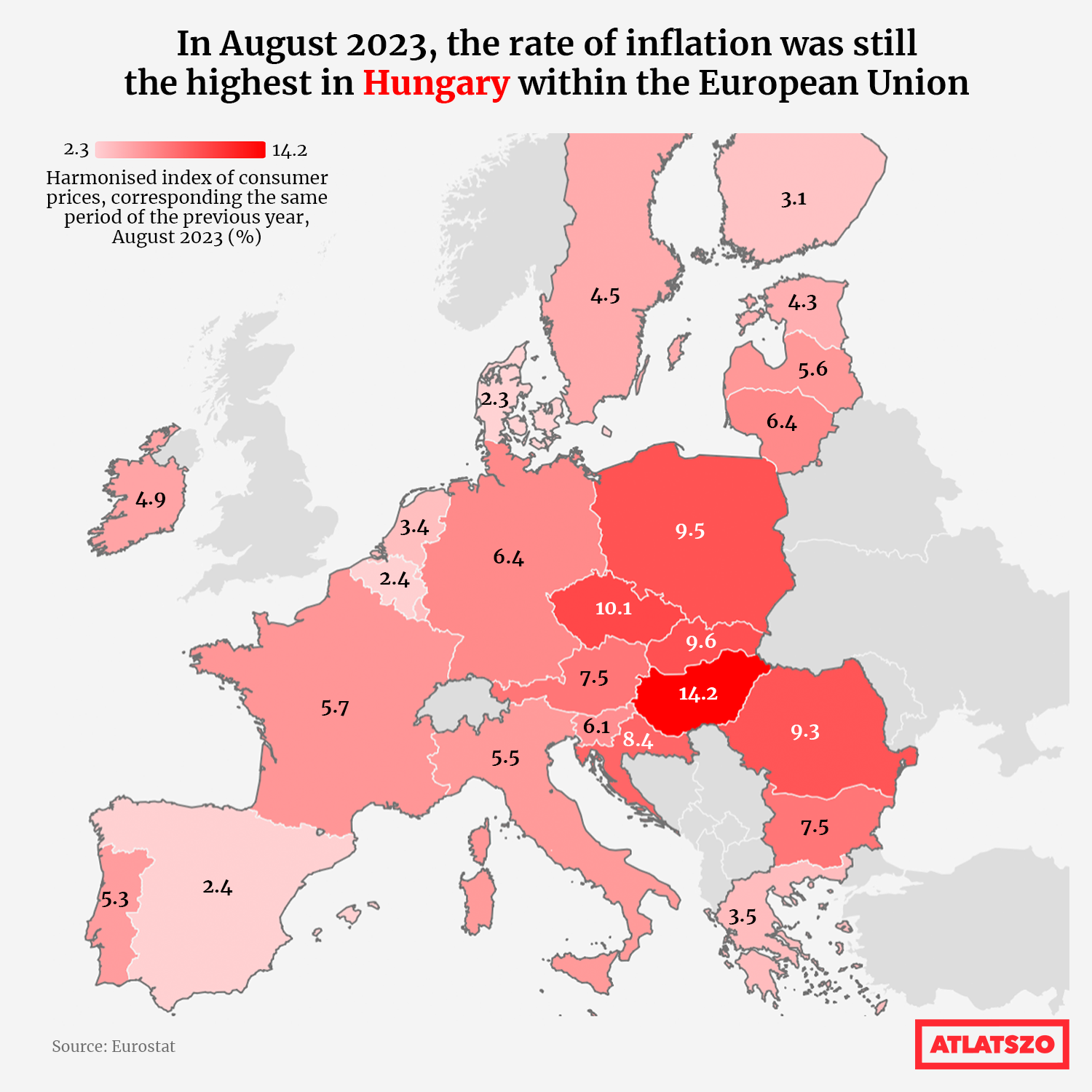

The moderation in inflation – that has been visible since the beginning of the year – continued in August. Although we still have the highest inflation in the European Union, we have started to catch up with the region. In Eurostat’s database, August 2023 is the last month for which we know the inflation rates of all EU Member States, so this is the latest month that we can take into account to make a comprehensive comparison.

Due to methodological differences, domestic inflation as measured by Eurostat differs minimally from the figures of the HCSO. In August, inflation in Hungary was 14.2 percent year-on-year, while the EU average was only 5.9 percent. Hungary was followed by the Czech Republic with a 10.1 percent rise, then Slovakia (9.6 percent) and Poland (9.5 percent). The EU average was just above Slovenia, where consumer prices rose by 6.1 percent.

In the European Union as a whole, Spain and Belgium had the lowest inflation in August, at 2.4%. Likewise, the European Union’s statistical office recorded mild inflation in the Nordic countries, at around 4 percent.

There is no wartime inflation, but propaganda

Since the outbreak of the war, the Hungarian government has regularly used the term “wartime inflation”. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán said that the root of the problem in the functioning of the Hungarian economy is war, and that as long as there is no peace, the war economy and war economic conditions will remain. In this regard, we compared the inflation rate in Ukraine since 2021 with that in Hungary. Until the beginning of 2023, Ukrainian inflation was higher than in Hungary. However, inflationary pressures in Hungary have been much slower to moderate over the course of this year than in war-torn Ukraine.

We asked Hungarian economist Péter Ákos Bod how much validity there is in the term ’wartime inflation’ in Hungary, and whether we can describe the current economic situation as such.

According to the expert, this is blatant propaganda, completely baseless. It is propaganda, because the whole wave of inflation in Europe, or even globally (which started before the war, in 2021) is linked to something much more general than the war, it is a global phenomenon.

Péter Ákos Bod said that there is a supply-side inflation on one hand. Suddenly it turns out that there is not enough fuel, not enough cargo workers, not enough containers to restart the world, and people are fighting for goods, raising prices. But there is also demand-side inflation, meaning: do people have money? If the government dumps an income supplement in, it makes it easier for prices to go up, because then people can pay it. Hungary is in recession at the moment, the economy is contracting, so that’s when inflation goes down.

It’s not the government that is holding back inflation, it’s the recession, the fact that people have no money – said the economist.

Last but not least, forint has lost the most value against the euro among the Central and Eastern European currencies in recent times.

As for expectations, according to Péter Ákos Bod, the research institutes see inflation in December at around 8 percent year-on-year, with price growth measured at the end of the already recessionary year 2022, and the annual average at around 18 percent. Then we’ll have to see what next year brings.

Written and translated by Luca Pete and Krisztián Szabó. The original, more detailed Hungarian verison of this story can be found here.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!