The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

‘Ukraine to Hungry sure shot’ – migration loophole at the Hungarian-Ukrainian border to be closed

According to two independent sources, the Hungarian Police practically banned non-EU and non-Ukrainian citizens in January from crossing the Ukrainian-Hungarian border. However, such an order would be illegal, as those who come from a country at war and seek Hungary’s protection should not be denied entry under the law. The Police did not deny or confirm our information. The measure may be motivated by the fact that some people are actually taking advantage of the war situation in Ukraine to facilitate immigration of non-EU citizens through the Ukrainian-Hungarian border in an organised way. We found plenty of evidence for this.

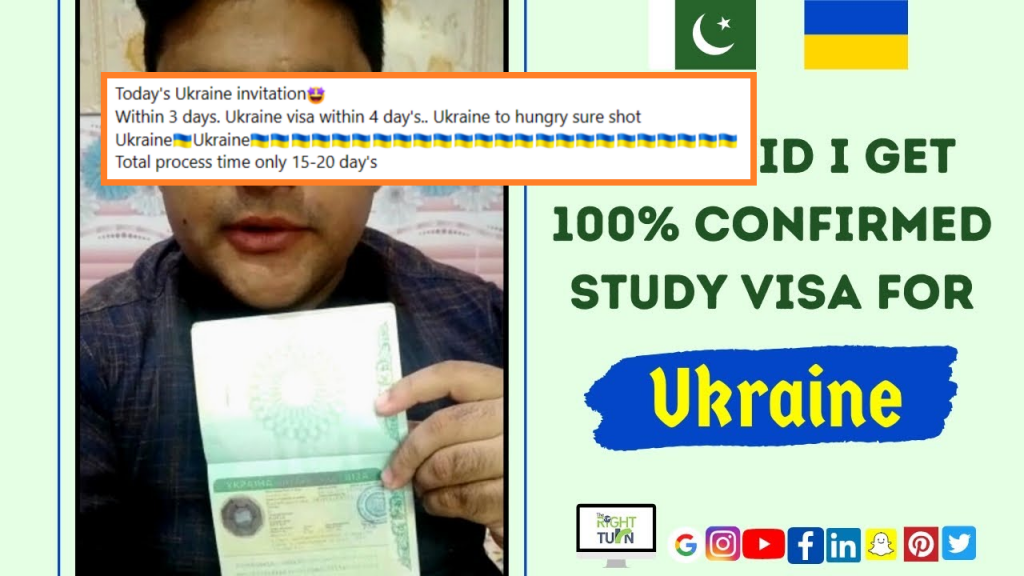

‘Peace be with you Pakistan. Peace be with you the world. Armaan Khan at your service again. Please listen to me carefully and understand me and if you understand then follow my instructions.’ – greets a man his viewers in Urdu language in a video message as he explains to his clients and prospective agents how to get to Europe smoothly as a Ukrainian university student. We found the video and similar social media ads through an e-mail announcement in November, in which a whistle blower raised Átlátszó’s attention to this method promoted by traffickers.

Their offer is to arrange your admission to a Ukrainian university and then, once you have your university papers, organize your visa to Ukraine and travel logistics. Often all the way to the Hungarian border, where the Hungarian police have (so far) allowed all entrants under the relevant legislation because of the war situation. Since the entrants have valid papers, in fact crossing the border is legal, so this can not be considered strictly as illegal migration like it way mentioned in the introduction. However, the way they got the necessary papers and reached the Hungarian border is not necessarily legally impeccable.

For foreigners to start higher education in Ukraine, first they must apply to a university and obtain an invitation letter (valid for six months). The invitation letters issued by universities are registered by the Ukrainian Ministry of Education and Science before being sent to the applicants. The letter of invitation enables the receiver to apply for the corresponding D-type visa valid for more than 90 days, provided of course that he/she has the required documents (passport, photo, etc.).

As described in a Ukrainian-language report written in 2021 about foreigners studying in Ukraine, some universities issue the invitation letters before the applicants have even passed the entrance exams and actually enrolled. So, based only on their application form and previous certificates, they receive an invitation letter which they can then use to apply for a visa and enter Ukraine – whether or not they then enrol in the university.

Let’s give back the floor for a moment to Armaan Khan, quoted earlier, who is educating his prospective business partners about all this:

‘The first step is the education documents for the applicant. If you do not have them, then you must arrange for them. Once they have been arranged, you must apply for admission to a university. It must be a good university and authentic university. The university must have certain support staff active to help you. Do not apply at universities that will not leave you halfway, leaving you in Moldova, or fail to clear the Ukraine border or not send you proper documents via DHL. Please do not apply at these universities.’

https://youtube.com/watch?v=TwSjrfu3LVk

The research cited above describes that the university application process is in most cases managed by intermediaries for the applicants, from submitting the paperwork to obtaining the visa to arranging travel. This is said to be partly due to the fact that certain things in the application process have to or had to be done in person in the past, which is obviously difficult for foreigners.

The report, at several places, suggests that the activities of intermediaries sometimes involve elements of corruption.

The researchers recommended to policymakers that the capacity of Ukrainian diplomatic missions abroad should be increased and the process should be at least partly digitalised so that applicants do not have to involve intermediaries. As they write, this would reduce the risks of corruption.

Intermediaries certainly do not work for free. “The service fee depends on the agent and the university. (…) It usually starts at $500-600. On average, people usually pay $1,000. It depends. (…) If you have your papers in order, it’s faster and cheaper.” (Meaning: if you don’t have your papers in order, it’s not a problem either you only have to pay more.) Apparently, corruption often starts already at the consulates, and intermediaries help to overcome this too. For example, the report quotes a Nigerian student who says

‘Coming to Ukraine for university is a big deal in my country. In every sense. From the invitation letter to the visa, of course. In Africa, Ukrainian officials are corrupt (…) Here you have to pay a bribe for a visa. At least six years ago, when I came, one had to pay. At that time you had to pay 3500 dollars for a visa. But I didn’t pay. If you know the right people, you don’t have to pay.’

However there were also different voices: “At our university, I can definitely say that we follow the rules (…) If the documents submitted are not correct, we will not issue an invitation letter even if the papers were submitted by our own trusted intermediary agent,”- an international coordinator at a Ukrainian state university told the researchers.

Embassies and authorities also involved

Our informer also claimed that embassies and authorities often cooperate with various intermediaries, agents, consultants and smugglers in arranging visas. Armaan Khan talks about this in the video in a flowery way, but before we give it back to him, a little explanation: agents often advertise and use the Kyrgyzstan-Turkey-Moldova route from the India region. People usually travel by plane to Chisinau and from there by bus via Odessa. Armaan Khan’s promotional video gives this information:

‘Please apply for the Kyrgyzstan visa once you have their admission letter with you. Once you have applied for a visa in Kyrgyzstan your visa will be granted. This is a known fact that visas are always granted at Kyrgyzstan. Now you have to arrive in Moldova with all your correct documents. You need to know some things about Moldova airport when arriving in Moldova. You must have knowledge and update. You must brainwash and inform and teach the applicants on how to clear the interview. Please provide the applicants with proper documents and knowledge to reach Moldova. Once they open applicant has reached Moldova they have to enter Ukraine the next day, through Odessa.’

In another video, he explains that it is also possible to obtain a transit visa “directly through our links in Moldovian immigration “. This is expensive, but it is the best way to get a transit visa. If you have all the documents, “you don’t need airport setting, but if you need airport setting as well, you can send me the documents and I will send them to our link in Moldova immigration “.

Incidentally, Moldova suddenly banned the issuing of transit visas to nationals of eight countries – Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Vietnam, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Afghanistan – for some reason, on 19 January, through a change in legislation. We have asked the Moldovan embassy in Kiev, which published the news, about the background to the amendment, but have not received a reply by the time this article was published.

Ads promise easy and legal access to the Schengen area

If you start looking, it’s quite easy to find similar ads and videos online. Entry with student visa is only one of the possibilities: there are agents who arrange work permits, very often in Romania or Serbia – from where many people try to enter Hungary, i.e. Schengen. According to Frontex data, half of all illegal border crossings take place via the Western Balkans route.

We were not able to verify the authenticity of the advertisements, but with the help of a Delhi contact, a graduate student in media communications, we made a random call to three of them.

One of them was extremely terse, telling us only that part of the journey would be by road. The second agent told us that we should fly through Nepal, where he has good old contacts with the authorities and can tell them in advance, so there is no problem with the check in. The entry point to Europe would be Hungary, but that would be by road. He has given a 100 per cent money-back guarantee if for some reason we don’t make it to Europe.

The third ‘businessman’ said that a university visa was slightly more expensive and time-consuming than the other options, but could be arranged. He offered to put us in touch with students already studying in Ukraine and, to everyone’s surprise, he indeed call a few days later. He connected our Delhi contact with the alleged student in a conference call, who claimed that he was indeed in Ukraine, but we could not verify this claim. It was a bit suspicious, however, that he was almost all praise for the agent, so it seemed more like a built-in marketing element.

In addition, our Indian helper asked around some of his friends, and two of them already had experience with similar advertisements: one of them paid 7,000 rupees to a smuggler who promised to take him from one European country to another, but after paying the money the advertiser disappeared. Another acquaintance, however, managed to enter a European country from Pakistan via Turkey with the help of an agent.

Many receiving an invitation letter do not enroll in Ukraine

We wanted to get an idea to what extent Hungary might be involved in this issue. We asked the Ukrainian State Center for International Education of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine how many letters of invitation were issued by Ukrainian universities last year.

According to their information, before the outbreak of the war, in January-February 2022, Ukrainian universities issued 5,965 invitation letters to foreign students, and 9,476 from March to November 2022. According to their reply, the largest number of invitation letters were issued in 2022 to the same countries from which the largest number of students came in previous years, i.e. India, Morocco, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Nigeria, China, Turkey, Egypt, Israel, Uzbekistan.

Unfortunately, we received no information on how many of the applicants who obtained an invitation letter actually started their studies. We also asked the Ukrainian State Border Guard Service how many people have applied for a D-type visa since the outbreak of the war, but we did not get any response.

We did, however, receive a list of the ten Ukrainian universities that had issued the most letters of invitation, and we wrote to all of them. Unfortunately, only one replied, saying that they had issued 150 letters of invitation since the start of the war, and only one of the applicants had actually enrolled. According to the information we received, most of the Ukrainian universities switched to online education because of the war, so it was possible to enrol online, but it seems that 149 people did not decide to do so in the end. However, we have no further information on them.

We also tried to get an idea of the gap between the number of university invitations and the number of students who actually started their studies in peacetime. The education centre reported that in 2021, 65305 letters of invitation were issued by universities. According to the research report mentioned earlier, around 20 thousand international students come to study in Ukraine every year. Since the total number of foreign students is around 75-80 thousand per year, we have interpreted that 20 thousand is the number of new entrants.

According to this, out of the 65,000 invitation letters issued, around 20,000 were actually used in 2021.

Of course, this does not tell us anything about what the remaining 45,000 applicants did with the university invitation letters they received.

Not only Ukrainians and Hungarians cross the Ukrainian-Hungarian border

It is an impossible task to obtain data on the number of border crossings of third-country nationals (non-Ukrainian, non-EU) that entered Hungary as university students or with a university invitation letter. According to a source, who asked not to be named, the Slovak border police are aware of this phenomenon and have detected it before, but the current legislation is more stringent in requiring proof that the person entering the country is fleeing war conditions.

All we could get from the Hungarian Police in a freedom of information request, after a month of waiting, was how many border crossings per month took place in 2022 at the Hungarian-Ukrainian border, and which countries’ citizens crossed. According to the data received, a total of 766,667 Hungarian and 1,293,401 Ukrainian citizens crossed the Ukrainian border between January and November 2022. As the figures for these two countries are much higher than for all other countries, they are not included in the chart for better visibility. (All data can be downloaded from here.)

The chart shows the peak after the outbreak of the war in March: at this time, it was certainly mostly foreigners in fact studying or working in Ukraine who fled to Hungary, genuinely fleeing the war and quite rightly seeking protection in our country. Certainly in later months many left their homes in Ukraine also because of the war, but it is also interesting to note the increasing number of Asian and, to a lesser extent, African citizens entering through the Ukrainian border in later months.

Since the outbreak of the war, after Ukrainians and Hungarians, it was Indian citizens who crossed the Ukrainian border in the largest numbers.

We don’t know what the rules are in Hungary at the moment

According to our information sources, on 20 January a new police order came into force, according to which third-country nationals are no longer allowed to cross the Hungarian-Ukrainian border, or at least only to a limited extent. We have asked the Police to confirm or deny our information and to explain the essence of the new procedure and what made its introduction necessary. After ten days, they finally responded, but we did not actually receive any answers to the questions we asked:

‘The police carry out their duties in accordance with Hungary’s Constitution, legislation and other public law instruments, which is no different in dealing with the migration situation following the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war. In order to ensure the entry, registration and temporary protection of persons arriving from Ukraine, the police staff shall implement the entry rules set out in the Schengen Borders Code in accordance with the Council Implementing Decision (EU) 2022/382 and the Regulation of the Government of Hungary No. 86/2022’ – they responded.

On 27 January, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee submitted a freedom of information request to the Police to find out what instructions are currently in force in this area, but so far they have not received a reply.

“Since the first day of the Russian aggression against Ukraine, we have been regularly present at the border and in places where refugees from Ukraine are being resettled, including villages near the border, where we provide legal assistance to refugees and those helping them. This is how we learned that police practices have changed and that they no longer let everyone who comes from Ukraine into the country.” – Zsolt Szekeres, the organisation’s senior legal officer, told us.

‘While the EU decision on asylum status and the Hungarian legislation may provide for different protection for those who were living in Ukraine before 24 February 2022, this does not mean that those who arrived in Ukraine after 24 February 2022 for whatever reason cannot be in need of protection. What is due process in their case can only ever be decided in the light of all the circumstances of the individual case. What is certain, however, is that if someone requests protection from Hungary, they cannot be turned back from the border. So far, the police have allowed everyone into the country from Ukraine. During entry, they check documents and whether anyone coming from Ukraine is asking for protection. For asylum seekers, asylum procedures are opened and alien policing procedures for all others.’

We asked the National Directorate-General for Aliens Policing (OIF) how this is done in practice and what the outcome of these procedures has been for those crossing the Ukrainian-Hungarian border. In its reply, the OIF said that “the National Police Headquarters is responsible for the questions raised”. Zsolt Szekeres (Helsinki Committee) said that although temporary residence permits are indeed issued by the police at the border, foreigners are then registered by the OIF, i.e. they should have relevant data.

The European Commission find the number of people who actually return to their country of origin after their asylum application has been rejected rather low. Statistics show that in 2021, 342,100 asylum applications were subject of a removal decision, but only 24% of them have actually left the EU. The asylum procedure is certainly not the same as the aliens policing procedure, but both types of procedure face similar difficulties and workloads in the Member States’ social care systems. On 24 January, Commissioner for Home Affairs Ylva Johansson announced a plan to increase the number of migrant returns. The Swedish Commissioner said this will be an important focus of the Swedish Presidency of the EU, which started on 1 January.

Armaan Khan says goodbye

‘This was a brief introduction to all people who want to start the work in Ukraine. I am available. My service charge is $500 for complete service from Pakistan to Ukraine arrival. Our expertise is available, And I can assure you, your money will not be wasted. Your clients will be happy and we have a very good success ratio. (…) Our means to earn a living has restarted and we can work. Please remember me in your prayers. Thank you.’

Written and translated by Orsolya Fülöp. Hungarian version of the story. Rishu Rani, Dr. Shabbir Hussain, Éva Vajda, Nicholas Nugent, Ranjit Ramchander and Mária Sarudi contributed to this report. Data visualisation: Krisztián Szabó.