The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Hungarian PEPs hide their wealth behind domestic private equity funds instead of offshore companies

In recent years, we have heard a lot about private equity funds which are gaining influence in many sectors by acquiring companies, while keeping the identity of the investors secret. In this article, we look at how these funds have effectively replaced offshore companies and we also outline the major private equity funds and how they are connected to the Hungarian government elite and politically exposed persons.

Hiding the money was not the original aim

The first investment fund in Hungary was created in 1992, and since then, their number has continued to grow. It is no coincidence that they are often referred to as the “new offshore”, even though their original purpose was not to hide money.

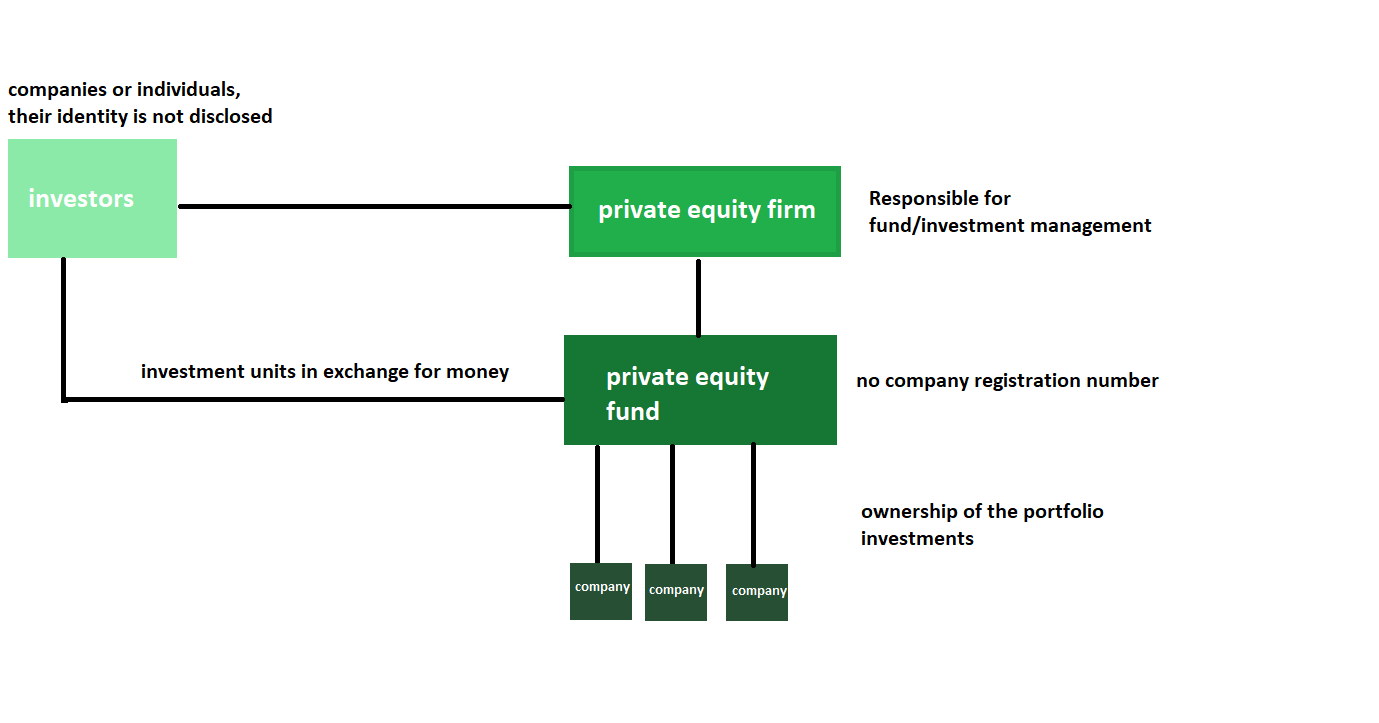

Private equity funds are closed-end, alternative investment funds. It can be set up for a minimum of 6 years, to finance the acquisition of companies or shares in companies. In simple terms, a private equity fund sets up or buys companies and then provides them with capital to finance their operations, often in return for a share in the company. Because they are private, their capital is not listed on a public exchange. As their name suggests, private equity funds invest in private, i.e. non-public companies. They usually finance the development of companies that have already gone beyond the early stage, unlike venture capital funds, which invest primarily in start-ups.

“Equity funds have basically been created and have become a very significant type of investment over the last 30 years for some serious and entirely professional reasons. None of these is to hide money or to hide the owners,” an expert on the subject told Atlatszo.

Hungarian regulation does not help transparency

The operation of equity funds is governed by a 2011 EU directive which includes a number of transparency requirements, including annual reporting obligations for all investment funds that operate or trade in the EU. However, the exact details are left to member states.

The Hungarian legislation entered into force in 2014. Three years later, in 2017, Szabolcs Szabó (opposition politician) submitted a proposal for an amendment to the law, which would require investment fund managers to disclose the name, address and, in the case of legal entities, the registered office of the holder of investment units if the holder holds at least 10 percent of the aggregate nominal value of the units.

It stated that the current provisions of the 2014 law “allow for opaque forms of ownership in Hungary” and that this “harms civic enrichment, harms the recognition of actual business performance, and is of serious concern from a national security, counter-terrorism and corruption perspective.”

That is, the proposal argued for transparency and the introduction of security guarantees because it would also be in the interest of the Hungarian market economy to avoid the creation of “internal offshore structures”.

The lack of transparency is a serious problem

The lack of transparency is indeed the biggest problem with private equity funds. Because if the fund is closed – i.e. it cannot publicly recruit investors – then the investor base remains completely hidden from the public, as funds are not obliged to disclose the names of investors, there is no register where information on who is behind each fund is available. The reason is that the investor is not the actual owner of the fund and has – in theory – no say in its operation, direction or control. The only person with these rights is the private equity firm which manages the fund.

“In principle, there is nothing wrong with the investors being unknown, although, as elsewhere, it cannot be ruled out that their capital may sometimes come from unclean sources. The problem is when the logic is reversed and the business decisions are taken by the investors rather than the private equity fund manager, and there are signs of this in Hungary. In such cases, the non-autonomous fund manager is pushed forward like a strawman,” – former finance minister of Hungary, Péter Oszkó explained HVG in 2017.

A new law is coming, but there will be exceptions

The Hungarian Parliament has just recently voted a law that will mean that the ultimate owner of a company can no longer be hidden. The legislation, which transposes EU anti-money laundering directives into Hungarian practice, will create a de facto register of ownership. However, according to HVG the legislation contains a number of exceptions and it is not at all clear what will be revealed by the register in the case of private equity funds.

As a matter of fact, similar registers already exist in several Member States, such as Malta. For example, the Maltese company that owns the luxury yacht Lady MRD is in fact owned by Hungarian businessman, László Szíjj.

László Szíjj is the beneficial owner of the Malta offshore company in posession of luxury yachts used by the Hungarian government elite

Over the last two years, we have written several times about the fact that the Austrian-registered luxury private jet with…

70 % of the funds can be linked to the government elite

Hungarian online newspaper Válasz Online has covered the topic of private equity funds in detail first in May this year and then at the end of November. “Since 2016, Hungary has seen a growing number of private equity funds, where registered fund managers are being pushed around by backers who are actually running the business” – the paper writes.

The most extensive network is that of Lőrinc Mészáros, the billionaire from Felcsút, friend of Viktor Orbán, who owns two private equity firms that are responsible for the management of the funds, and through them a total of 13 private equity funds. His acquitances also has a good number of funds, like his business partner, László Szíjjj, who has won many state and municipal contracts with his construction companies and according to the Forbes magazine’s latest list Szíjj is the 9th wealthiest Hungarian.

A board member of Mészáros’ company, Ádám Balog, owns one fund manager and four private equity funds. József Tamás Kertész (also known as Mészáros’s lawyer), who is the founder of the Fidesz media holding, has two private equity funds.

Two firms of Bálint Szécsényi, who has business relations with the Prime Minister’s son-in-law István Tiborcz, operate a total of nine funds. One of them for example is behind the real estate project in Balatonhenye:

Another huge private estate is being built by the business circle of the Prime Minister’s son-in-law

Balatonhenye is a tiny village north of Lake Balaton in a beautiful area which is a candidate for the UNESCO…

István Száraz – who, according to press information has good relationship with the son-in-law of Orbán – manages a fund manager and altogether six private equity funds.

The first wife of the Prime Minister’s Chief of Cabinet (Antal Rogán) or more precisely her partner, Ágoston Gubicza, is the manager of the largest private equity fund in Hungary, GB & Partners Venture Capital Fund Management Ltd., which manages three funds. There is another private equity firm that can be found in Rogán’s circle of acquaintances: Gábor Földvári – whose name is best known from the so called The Hungarian Residency Bond program which allowed non-European Union citizens to acquire Hungary’s permanent residency status by investing at least €300,000 in special Hungarian government bonds. The proposal was put forward by Antal Rogán, and two years later, G7 revealed that the scheme had brought 162 billion to Fidesz-linked offshore companies. What is more, fictitious bonds were also traded in the programme. Attila Boros, who currently owns a fund manager and two equity funds, was also a beneficiary of the residency bond deal.

Businessman Dániel Jellinek, CEO of the Indotek Group, 11th richest Hungarian according to Forbes, owns two fund management companies and six funds. The CEO of 4iG, Gellért Jászai owns four private equity funds. The company – which has been boosted by numerous state contracts – recently appeared in the news when it managed to acquire a majority stake in Antenna Hungária Zrt. (national telecommunications company,) thus, establishing a telecommunications super holding.

Private equity funds linked to the Hungarian government elite

Other businessmen are also successful in the market: OTP Group, headed by Sándor Csányi, has five private equity funds, Zsolt Hernádi, CEO of Mol, honorary citizen of Esztergom, who was sentenced to two years in Croatia for bribery, is responsible for two private equity funds.

Válasz Online’s article also shows that many private equity funds were created during the coronavirus pandemic, with nearly eighty of them now in existence, and 70% of them linked in some way to the pro-government elite.

In May, the paper counted only 60, of which 43 were in the hands of people close to the currently ruling political party, Fidesz-KDNP.

As a consequence, we can see that Hungarian private equity funds are hardly managed by actual, independent participants, and since the spring there has been an even stronger trend towards such financing of large acquisitions of the government elite. What is more, these funds are also often the direct or indirect beneficiaries of state and EU subsidies.

Written and translated by Zita Szopkó. The original, more detailed Hungarian version of this article is available here. Cover photo: Viktor Orbán and Lőrinc Mészáros (Fidesz-KDNp) mayor of Felcsút at an inaugurationin Alcsútdoboz, Fejér County, on 18 November 2014.

Support independent investigative journalism in Hungary, become a patron of Atlatszo on Patreon!

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!