The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Cucumber Cultivation Helps Lift Up Hungary’s Poorest

The Kiútprogram (Way Out Program) supports people living in extreme poverty in the north-eastern part of Hungary. Families start growing cucumbers in their own gardens with the help of micro-loans provided by the programme. The families can earn up to half a million forints extra income in a season. Although the programme is not welcomed by all municipalities, there are some successful followers in the country. However, the hope that the government would adapt the programme has not been achieved, so for the time being it remains an isolated initiative funded by a philanthropist.

Timi, a mother of two in the village of Fábiánháza in northeastern Hungary, started growing cucumbers commercially in her backyard last year. She joined the Kiútprogram (Way Out Program) on the advice of a neighbor for whom she had worked as a day laborer.

“They gave us everything to start with: the seedlings, the nets, the spray, I followed all the advice my mentor gave me, which is why the cucumbers turned out so beautiful. I couldn’t have started without help; it cost a lot of money to buy the equipment. This little extra money [from selling cucumbers] helps me a lot, as I have two children. In one season I should make half a million [forints, about $1,700] but it will depend on the harvest. I want to use this year’s money to finally do the children’s room,” says Timi.

Péter Felcsuti, a retired bank executive and a member of the Way Out board of directors, says it is the only such initiative in Central Europe, “where education and mentoring combined with work is provided to people living in extreme poverty.”

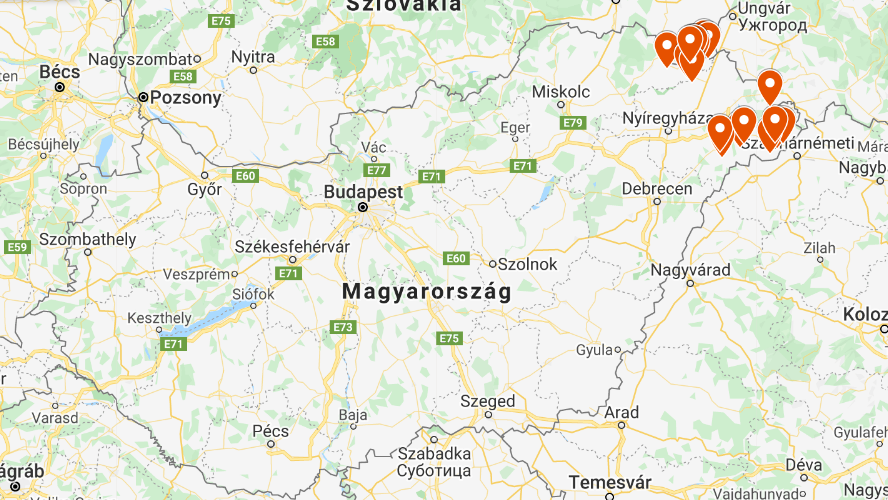

Way Out is active in 17 villages in two northeastern Hungarian counties with large Romani populations. Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg and Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplen counties are among the poorest. Some program clients pump their drinking water from street wells.

In 2020, the program won a SozialMarie prize, given to social innovation projects in Central Europe, and has earned plaudits from the World Bank as an example of good practice in expanding economic opportunities. “Cucumber farming generates sufficient income for families in the poorest region of Hungary,” the prize jury said, praising Way Out as “a classic blend of a microcredit program and mentorship with a socially innovative response.”

Like other clients, Timi received a microloan in the form of cash and a commodity credit.

The cash loan, with a maximum of 150,000 forints depending on the amount of land farmed, can be used for the initial capital investments such as well digging, irrigation equipment, and stakes. The loan must be repaid within one or two years, depending on the amount.

The commodity credit covers seedlings, fertilizer, and other ongoing costs. Timi and other farmers in the program don’t need to peddle their crop. The program buys their cucumbers and pays them every week during the season, then delivers them to a local pickle factory. Cucumber farming helps participants make ends meet during the May to September growing season.

Learning From Mentors

Way Out employs mentors who select the program participants, usually relying on local contacts who know the families. The mentors provide advice on cucumber cultivation and help with paperwork. “Many [participants] have never been in business before, so there are a lot of problems that [might] seem trivial to others that they need help with,” Felcsuti says.

The program’s motto is “Give me a net, not a fish.”

Participants learn not only how to grow cucumbers for pickling but also how to become entrepreneurs. “They experience that they are useful members of society,” he says. “This gives them self-confidence; many of them can move on and find other ways to work and earn an income in the ‘white economy.’ “

The program has been running in northeastern Hungary for more than a decade under the auspices of a nonprofit set up in 2009 by businessmen András Polgár, András Ujlaky, and Felcsuti. Professional help was also requested from György Molnár, economist at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The program is based on the microcredit model pioneered by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus, founder of Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank.

Since 2013, the programme has been sponsored by a philanthropist

Initial funding for Way Out came from a European Union grant worth nearly 1.5 million euros. It was topped up with private donations and 350,000 euros in state budget funds. Since 2013, the organization has operated without state or EU support, thanks to funding from the Polgár Foundation and private donors.

Way Out client Timi says the extra income she earns goes a long way in her household. Source: Way Out.

Way Out’s financial reports show that the launch was costly. Between 2010 and 2012, only about 15 percent of the funding was spent on loans. The rest went into setting up the system, paying field workers, and taxes and social contributions. Loan repayments also were problematic; in the early years, clients repaid only 55 percent of borrowed funds. Repayment rates have risen, although a poor harvest or bad weather can push them down. The program uses its own resources to cover unpaid loans.

Lessons were learned as a result of those difficult early years. For example, when it was determined that companies that sold seedlings, fertilizer, and other materials were charging too high a price, the program took that over. And in 2012, Way Out staff began scrutinizing potential clients more carefully to screen out those who took the money but had no intention of becoming cucumber farmers. They had to accept that they could not help all people living in extreme poverty. Coming face to face with this reality every day took a heavy psychological toll on the mentors at first. The initial cohort of 37 that passed an exam to become a mentor soon shrank to 12, and cost-cutting measures brought the figure down to four, even though this meant shrinking the geographical coverage of the program.

Cheaper Than a Public Jobs Program

Many former Way Out clients are now self-employed, program managers say. In 2020, 25 people were helped into long-term factory jobs.

Since cucumber farming cannot provide year-round livelihoods for families, in 2018 the program began assisting clients to integrate into the labor market, helping them find work in agriculture processing or in companies making mirrors, eyeglasses, and other products.

According to the banker, this private initiative makes better financial sense than a public-works program. “The monthly cost per client is essentially the same as the monthly cost of employing a person in public employment, and overall it costs less than a public works program,” he says.

In 2020, Way Out clients produced and sold 316 tons of cucumbers, generating a net income of 51 million forints ($173,000), according to the program’s annual report. The crop fetched 25 percent less than in 2019 because unusually cold weather in the spring and early summer reduced yields. The revenue was shared not only by the 63 families that signed contracts with Way Out but also by those who worked as day laborers for clients who cultivated larger areas.

The total number of producers stayed stable during the coronavirus pandemic – 63 in 2020 compared to 64 in 2019. There were 18 new producers in 2020 – 11 fewer than the previous year. Figures for this year are not yet available.

“The coronavirus has not affected the production itself or the purchasing,” says Way Out communications manager Ilona Gaal. “However, fewer people applied. They were distrustful; they were afraid of what would happen if the coronavirus meant that no one would buy the cucumbers.” During lockdown periods, recruitment was done through online platforms and phone calls, and clients were met outdoors.

When the pandemic forced businesses to shutter, many informal or casual workers lost their jobs. But the demand for unskilled labor quickly rebounded after restrictions eased. In addition, a donation campaign has so far raised 730,000 forints in emergency aid for a total of 96 families.

Unpaid loans, wages for field workers, and office staff and infrastructure have to be financed. According to the 2020 annual report, program managers earmarked 50 million forints for expenses; in terms of income, 2 million forints came from private donations, and corporate grants contributed another 11 million.

Way Out channels the profits back to its clients, but the growers never know just how much they will earn. Weather is always a factor – three big storms hit the region this year – and the price of their produce fluctuates. This year, cucumber prices fell significantly as local buyers took advantage of cheaper produce from Slovakia, Gaal said.

Spreading the Word

The success of Way Out has reached other parts of Hungary. In Baranya County in the south, 20 indigent families grow cucumbers in a similar program, supported by the European Union since 2017. The annual costs of this initiative are estimated to reach 7-10 million forints, which will have to be covered from other sources when EU funding ends in 2022.

The program is run by József Kőműves, mayor of the village of Bikal. He and Erika Gulácsi, mayor of nearby Szalatnak, are the only program staff in the county, and they also serve as program mentors. The two mayors learned to grow cucumbers from Way Out staff, visited the cucumber fields, and have stayed in touch with their Way Out counterparts.

Village mayor Erika Gulácsi is a mentor for cucumber growers and sells their produce out of a van. Source: Highlights of Hungary.

Baranya County program clients are doing well if they earn 500,000 forints a season. The monthly income of an employee in a low-skilled public jobs scheme is 54,000 forints, or 650,000 forints a year. “So the money earned from pickling cucumbers can almost double a person’s income,” Gulácsi says.

Here, cucumbers grown by clients are sold directly to customers. The two mayors handle sales after fulfilling their official duties. Gulácsi sells from a van in local villages, while Kőműves leaves for the market in Pécs at 3 a.m. to sell to retailers there. Kőműves said production has not been disrupted by the coronavirus epidemic, but the inability to meet people in person during lockdowns hindered recruitment of new families to the program.

Gulácsi, who received a Highlights of Hungary Ambassador Special Award this year, says the program offers its clients meaningful work.

“Finally, they could do work that made sense, not just sweeping leaves from one side of the street to the other. They started to think about how they could earn money. We recently got together for a meeting and the idea came up to make Christmas decorations from materials collected from the forest,” she says.

In addition to helping people living in extreme poverty earn income, Way Out helps them out of their “hopelessness,” says Zsombor Farkas, an assistant professor in the Institute of Social Studies of Eotvos Lorand University. This is quite an achievement, he remarks, as it is not easy to get people who have been living in deep poverty for decades back to work.

Way Out’s founders anticipated an even greater reach. They hoped the government would provide funding and maybe even adopt the program countrywide. But with the conservative Fidesz party in power since 2010, the poor have been left on the sidelines, Farkas says. But even if the initiative cannot make a huge impact on society as a whole, it can – and does – make a great difference in the lives of individuals in deep poverty.

Translated by Transitions Online. The English version of the text was first published on Transitions Online. The original, Hungarian version of this article was written by Szilvia Zsilák and can be found here.

This article was published with the support of Transitions Online (TOL) and Mertek Media Monitor. The Hungarian company data was provided by Opten Kft. Cover photo: One of the families who participate in the programme. Source: Way Out.

Support independent investigative journalism in Hungary, become a patron of Atlatszo on Patreon!

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!