The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

András Bereznay: Treaty of Trianon was a mockery of the principle and right of self-determination

At the end of 1918, multinational Hungary was among the losers of the First World War. It did not follow from any of this that the victors needed to impose on her a century ago in the Trianon treaty the extremely harsh measures they did, especially in a territorial sense. Nor did that follow from the events of the period between the end of the war and the concluding of the treaty. The plans, including secret treaties, were ready beforehand.

András Bereznay is a Hungarian-born cartographer and historian, specialising in the compilation of maps for historical atlases. Born in Budapest, he left Hungary in 1978 and is based in London. Bereznay has researched and compiled historical maps, on a great variety of subjects, for numerous publishers. He has a particular interest in ethnographical and other thematic maps.

Hungary had been part of Western civilization by then for over nine centuries, sharing its values, including the most defining one, the principle of self-determination. The latter’s content had widened through the ages, and by about this time was widely acknowledged to also apply to ethnic groups. For Hungarians the least tolerable aspect of the treaty to absorb was the contradiction of its measures to this western value.

The inconsistency of those dictating the terms is conspicuous not just in the Trianon treaty itself, but its comparison with treaties concluded with other states on the losing side. This was manifested not just in the frequent superseding of the principle of self-determination when it came to masses of the Hungarian population despite quoting it when rationalizing the detaching from the country her minority inhabited areas, but also in the selective application of plebiscite as in the context ideal means for exercising democratic will.

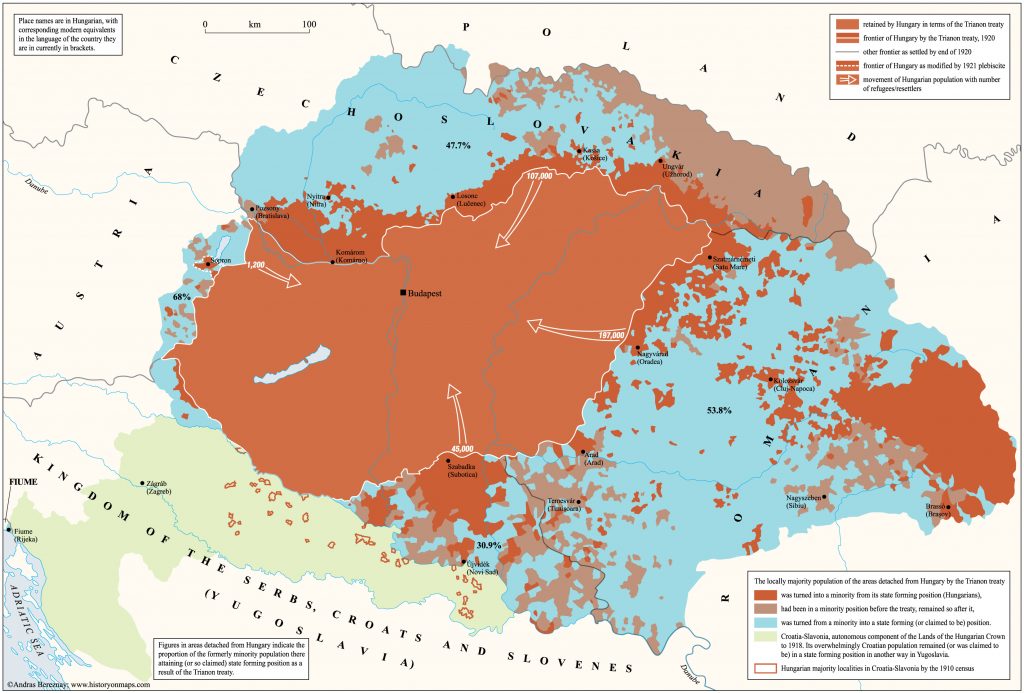

It was an odd application of the principle of self-determination that considered necessary to dismember Hungary that – disregarding autonomous Croatia-Slavonia which was choosing to secede – had a Hungarian majority of 54.5% so as to transfer to Czechoslovakia a territory where the proportion of the Slovaks was 47.7%1 and another to Roumania where the proportion of Roumanians was 53.8%. This, while the state forming position of the Slovaks in the new Czechoslovakia – the very justification for transferring land they inhabited to Czechoslovakia – was at least not without ambiguity; and as to Roumanians, amounting in total to 16.1% of the population of hitherto Hungary securing self determination for – not even all of – them involved the transfer to Roumania a larger territory than allowed by the treaty to be retained by Hungarians who were forming 54.5% of the inhabitants of the partitioned country. Simultaneously the state named then Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia) came to possess three such areas of Hungary where even the combined total of all Southern Slavonic population (Serbian, Croat, Slovene, Šokac and Bunievac) was merely 30.9% according to the 1910 census. The state forming position of the non-Serbians in this area (just as in joining to this new state Croatia-Slavonia) remained in various ways mere fiction.

Delegating over 3.3 million people, i.e. one third of all Hungarians into a minority position contradicted unequivocally the principle of self-determination. Their number was substantially higher than that of either the seceding Roumanians or of the Slovaks, not to mention that of the Southern Slavs which was amounting to a mere one-seventh of this figure. Besides, the concept of self-determination was not served by the fact that there was as a result of the redrawing of the frontiers an about two and a half million strong population transferred from a minority position in Hungary to the same position in the successor states. Being moved to another state meant no improvement for them from the standpoint of self-determination. It meant instead a major upheaval effecting them only detrimentally, given the series of ways in disrupting their way of life hitherto. Thus even if assuming that the Slovaks, Roumanians, Southern Slavs and the western Transdanubian (Burgenland) Germans all desired to secede – and there were tangible signs to the contrary – the treaty brought improvement even then to the position of only about 5.2 million people, at most. It achieved that at the price of worsening simultaneously the position of about 5.5 million other people. Viewing this from a general Western standpoint, it was hardly worthwhile to bring about such ‘gain’ by destroying a traditional unit that was functioning for 900 years as one of the pillars of the state system of the West. The collapsing of this pillar contributed to the destabilizing of that system, thus affecting the West as a whole detrimentally.

Interactive feature – native language ethnic map of historical Hungary in 1910

After creating a map of the ethnic and the religious composition of Hungary based on the 2011 Census, now we’ve made an interactive version of the native-language ethnic data of the 1910 Census. The geoinformatic data for the administrative boundaries of the municipalities in .shp extension come from the GISta Hungarorum project’s site.

The principle of self-determination having been in the case of the Trianon treaty a mere catchphrase is unmistakably clear from the victors not wishing even to hear about plebiscites to be held – although suggested by the Hungarian delegation – in the territories assigned to be detached concerning their fate. They were pointing instead to decisions of national assemblies of dubious legitimacy, convened together in haste, uncertain if reflecting democratically the collective will of the various minorities. What more, they have done so without taking in account the decisions of those such assemblies that decided for remaining in Hungary.

Interactive map: see the movement of Hungarian migrants and refugees after the Treaty of Trianon

István Dékány has recently published the online database that accompanies his book titled Orphans of Trianon (Trianoni árvák). The database contains data about Hungarians who were either deported from their homeland or who fled their homes after the Treaty of Trianon was signed in 1920.

This was inconsistent further by comparison with the other post-war treaties. Whilst it is customary to the level of amounting to a cliché to refer disapprovingly to the extreme harshness of the Versailles treaty to Germany – and not without reason – its conditions, especially concerning territory were almost incomparably milder and certainly much fairer than those of the Trianon treaty to Hungary. Minor linguistic islands and Alsace-Lorraine (the German-speaking inhabitants of which were traditionally of a pro-French sentiment) apart, that treaty not only did not detach German speaking areas from Germany but allowed in the main the minority populations of various areas to decide by plebiscite if they wished to secede. The Polish speaking Masurian (and some other) parts of Germany decided for remaining in Germany. It was thus apparent that it did not necessarily follow from the linguistic conditions of the population where they wanted to live; economic considerations and conservatism could prove to be more decisive than the attraction of their ‘mother nation’. This could well have been the case in at least some minority inhabited areas of Hungary if people were not denied the chance to decide.

Austria, it is true, was deprived of significant German-speaking territories, but at least in her mainly Slovenian inhabited southern Carinthia a plebiscite was held – the result deciding for Austria. Also, Austria was compensated to some extent for her losses – by receiving Hungarian land. Bulgaria lost in the main – and only partially – territory she had gained a mere six years earlier. Compared to the losses of Hungary, both the size and proportion of this was negligible. The Ottoman Empire, whilst having to give up its Arabian possessions (also Germany’s colonies were taken) there was little intention to detach Turkish-speaking area from her even in the Sèvres treaty, which was annulled due to the Turkish resistance to it. That treaty even foresaw a plebiscite for a sizeable Kurdish-inhabited land.

Trianon100: maps of public spaces in Hungary named after settlements in the detached territories

For the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Trianon, we created interactive maps of Hungarian public spaces that were named after the settlements in the territories detached from the former Kingdom of Hungary in 1920.

There was much traumatized, thus unhelpful soul searching among Hungarians for an explanation as to what had lead to the wholesale disregarding of a core Western principle by leading Western powers that, adversaries or not, had been highly respected. There was much misguided effort to internalize the explanation. It is nonetheless unwarranted to seek it in the Hungarian treatment of minorities. Despite a prevailing ‘bad press’ to the opposite – advanced by the victors and a desire to rationalize a deeply unjust deed – it was, if compared under proper scrutiny against contemporanous European standards, in fact exemplary, or at the very least in no way worse than that of any other state of the period. Indeed, the very victors were never referring to any retaliatory intent in the treaty terms. There is no reason to seek an explanation in other than a benevolent indifference of the Entente powers towards the excessively covetous craving of Hungary’s neighbours – their erstwhile allies – for unrestrained expansion, combined with an as shortsighted as it was unprincipled expectation for the latter’s services to come in the future.

It does shed an unfavourable light on the victorious powers that the sole plebiscite in Hungary that was allowed to be held – not before the concluding the Trianon treaty – about the fate of Sopron, took place not out of a respect to the right of self-determination, but in view of armed resistance in western Transdanubia.

The answer: autonomy

The Trianon Treaty concluded a century ago has done – as widely acknowledged by now – great injustice to Hungarians by its wholesale disregard of the principle of self-determination. The injustices included, inter alia, the delegating of one third of Hungarians for no good reason to countries neighbouring Hungary. These Hungarian minorities were in times to come often oppressed, if not outright persecuted, and even today their situation in most places cannot be said to be satisfactory in terms of ethnic human rights.

The instinct in the decades following the treaty’s implementation was to seek remedies to injustice by modifying state frontiers, rendering them more harmonious with ethnic frontiers, thus more suitable from the standpoint of self-determination for all. Such efforts, whether hoping for revision by enlightened powers taking up the cause of the Hungarians after becoming convinced by the power of reason, or relying – tragically for all concerned – on force, or implied force, all failed, or when brought success, it proved to be ephemeral.

Experience, and the changing thinking about such matters after WW2 led to an acquiescence to the Trianon frontiers, or their slightly modified version created by the 1947 Paris treaty, in Hungary herself, at the very least among her political class. That the country resigned to never regaining lost territory nor receiving fair treatment in terms of the location of state frontiers, however, did not make the problems of the Hungarians in minority since the Trianon treaty go away.

They were merely ignored, now by all, and allowed – especially under Communism – to suffer in silence. This was so even if a formal gesture was made to them during Communism’s darkest, Stalinist days in Romania. Under Soviet influence for reasons of ideology an at least nominally autonomous territory was established then for the Hungarian inhabitants of Szekelyland. It took for the Romanian Communists just eight years to dilute and diminish in extent that already much precarious autonomy. In another eight years, Ceaușescu, Romania’s national ‘Stalin’ took care to abolish it altogether so as to eradicate any trace, even a reminder, however nominal, of Hungarian collective territorial rights.

Minority issues are not an exclusively Hungarian concern. It was recognized in Europe after WW2, where the concept of territorial autonomy – whilst relied on sparingly prior to the war – was never unknown, that the best approach, if conflict was to be avoided, to issues involving territory was the generous granting of territorial autonomy for minority inhabited areas. It became clear that it was the most suitable device to satisfy legitimate aims for exercising rights due in the terms of the principle of self-determination, simultanenous with doing away with territorial claims and counterclaims on ethnic ground, thus with rivalry, recriminative bitterness, even war among nations.

Thus by now, seventeen European countries allow for some kind of autonomous self-government. A few are built on the self-government of their constituent parts. In the case of a number of others, no such arrangement can be made given their size. In yet other cases, no claim for ethnic-based autonomy is to be expected in view of the population’s homogeneity. In the majority of European countries where territorial autonomy is a notional possibility, its granting has become standard practice.

However, Romania is refusing to allow for the autonomy of the overwhelmingly Hungarian inhabited Szekelyland. This despite the population having expressed democratically its will at a self-organized referendum to acquire it. Romania is thus striving to perpetuate the prevailing administrative disenfranchisement of the Hungarian (Szekely) minority.

Whilst it is true that Romania is not the sole European country containing a compact minority area without autonomy, she is the only one holding a land the formerly recognised autonomy of which the state withdrew. The sole other example in Europe after 1945 for the withdrawal of an existing ethnic based territorial autonomy is that of Kosovo. It is noteworthy that the negation of rights there led to secession, but not before much bloodshed, human misery.

The map above aims at contrasting the post 1945 situation of autonomy-seeking Szekelyland with that of other not independent, yet self-governing areas of Europe.

Written and illustrated by András Bereznay.

This work was partly published in András Bereznay (2020): Trianon: self-defeating self-determination, in: Regional Statistics 10 (1): 151–156.