Hungary’s Regulatory Authority for Regulated Activities (SZTFH) ordered the online betting platform Polymarket to be blocked in the country under suspicion of illegal gambling. Polymarket hosts a betting option for the upcoming Hungarian election, where Péter Magyar currently leads in the odds – one user even bet over 225,000 USD on this outcome. But while some see Polymarket betting odds as an alternative to opinion polls, history shows that those who bet money are wrong more often than pollsters.

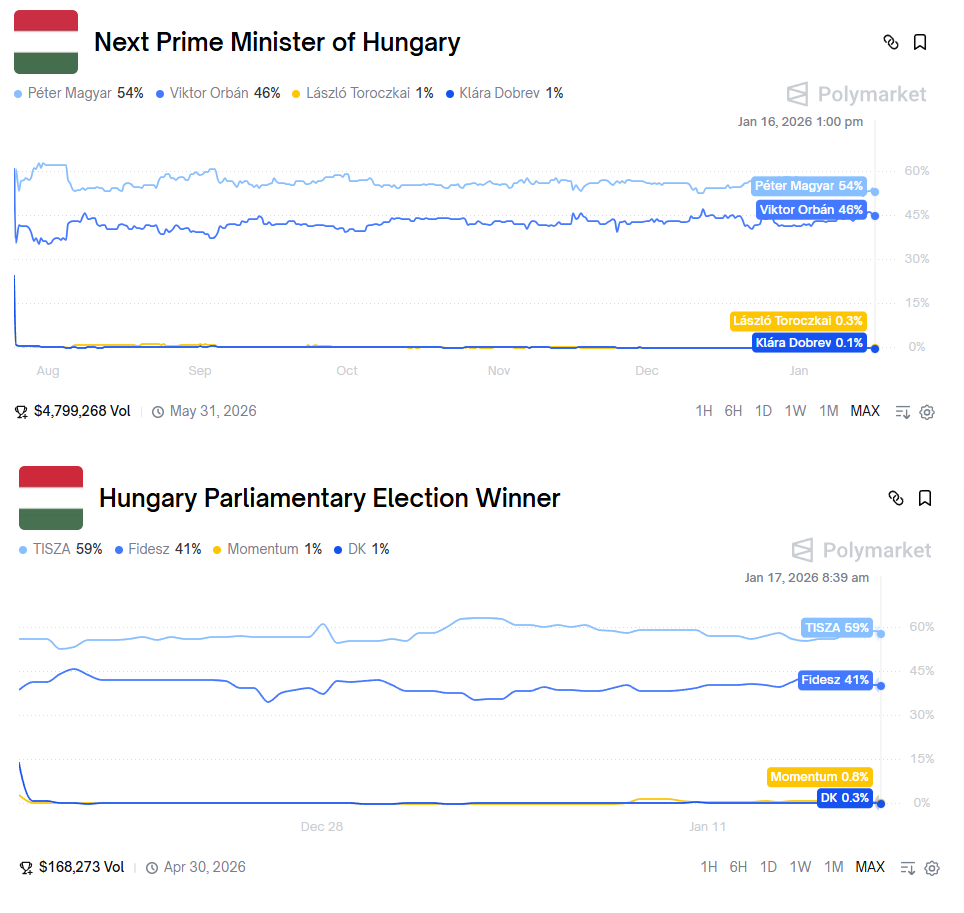

Polymarket’s betting odds currently give the opposition Tisza Party a 59% chance of winning the Hungarian parliamentary elections in April, while the governing Fidesz stands at a 41% chance. In another bet on the next Hungarian prime minister, Péter Magyar is favored over Viktor Orbán by 54% to 45%.

The latter bet attracted national attention after one user started betting massive funds on Magyar’s victory, currently holding over 225,000 USD in “Magyar wins” positions.

Polymarket’s odds reflect recent Hungarian polls, which indicate a 5- to 10-point edge for the opposition party.

However, since the morning of January 19, Polymarket has been unavailable from Hungarian IP addresses because the Regulatory Activities Supervisory Authority (SZTFH) is investigating whether the site constitutes illegal gambling. Until a final decision is made, Hungarian networks are blocking the site, so it can currently only be accessed from Hungary using a VPN.

Stock exchange for politics

Although betting on political outcomes such as elections is not new, Polymarket innovated by calculating odds automatically, using a market-based pricing system similar to the stock exchange. Traders can buy “yes” or “no” shares linked to the outcome of an event. The price of these shares varies according to how traders price the odds. As with traditional betting, the bets that pay the highest odds are those that, according to the betting community, have the lowest probability (for example, a surprise victory by a small party).

Based on this, Polymarket generates a percentage curve that shows the changing odds according to the betting market. This curve has been compared to and even posited as an alternative to similar curves compiled from polling averages.

When the bettors got it right

The idea that betting markets represent public opinion better than polls was seemingly confirmed when Polymarket confidently predicted Donald Trump’s victory in the US elections.

A month before the presidential elections, the betting market favored Trump over Kamala Harris, and his odds increased in the following weeks, although the gap narrowed slightly just before election day.

At the same time, most opinion polls underestimated Trump’s and overestimated Harris’s popular support by 1–2 percent,

with few predicting that Trump would win the popular vote.

On a state level, however, the picture is a bit more nuanced. Although Trump won all swing states, Polymarket gave around 50/50 odds for states like Michigan and Pennsylvania, sometimes favoring Harris. Out of election outcome models, Hill’s Decision Desk HQ proved to be the most accurate, giving Trump a 54% chance of victory immediately before the election. Other forecasts considered Harris more likely to win, but the difference was typically only a few percentage points.

When no one was surprised

However, the US election seems more like an exception than a rule. Typically, Polymarket odds are harmonious with polls. Most of the time, both pollsters and bettors are vindicated on election day.

This was the case, for example, in last year’s Czech elections, where ANO’s victory came as no surprise to either pollsters or the betting markets. Andrej Babiš’s party led steadily throughout the campaign, both in the polls and in Polymarket odds.

The same was true for the Norwegian and German parliamentary elections, as well as the Croatian and Irish presidential elections. In all four cases, the winning parties and candidates led steadily in the polls and among bookmakers.

This is not surprising, given that opinion polls have a strong influence on betting odds, evidenced by the fact that the comments in most markets regularly quote opinion polls.

When everyone got it wrong

Of course, there are plenty of examples of pollsters getting it wrong. In such cases, however, the market is usually just as wrong.

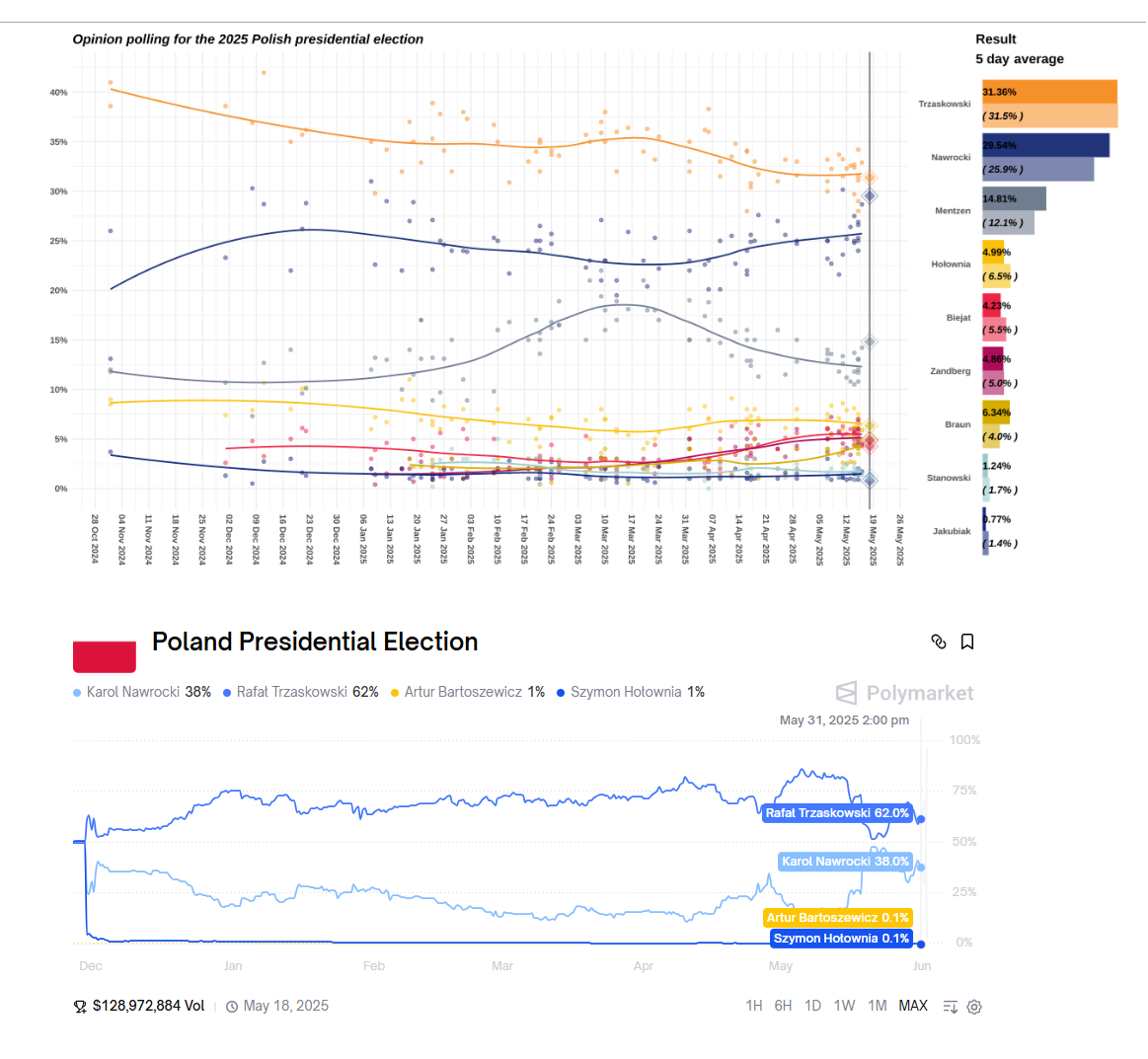

In last year’s Polish presidential election, both Polymarket and pollsters predicted a victory for Rafał Trzaskowski. A month before the election, Polymarket gave his opponent, Karol Nawrocki, less than 25% odds – yet he ended up winning the election by a narrow margin.

The possible winner of the Polish presidential election according to opinion polls (yellow: Trzaskowski, dark blue: Nawrocki) and Polymarket.

The same thing happened six months later in the Dutch elections. Geert Wilders’ party, the PVV, led in the polls from the beginning to the end of the campaign, which is why it came as a surprise that on election day, it was not them but the liberal D66 that received the most votes.

Polymarket’s odds also predicted a PVV victory until the very last moment.

A month before the election, they gave D66 only a 0.4% chance of winning, and even on the day before the election, Polymarket’s indicator showed only 8.5%.

Although pollsters also overestimated the PVV, they were more accurate in this case. According to opinion polls, the PVV’s lead had declined in recent months, with the latest surveys showing a difference of only 1–2%. An Ipsos poll correctly predicted D66’s victory.

When the market gets it wrong

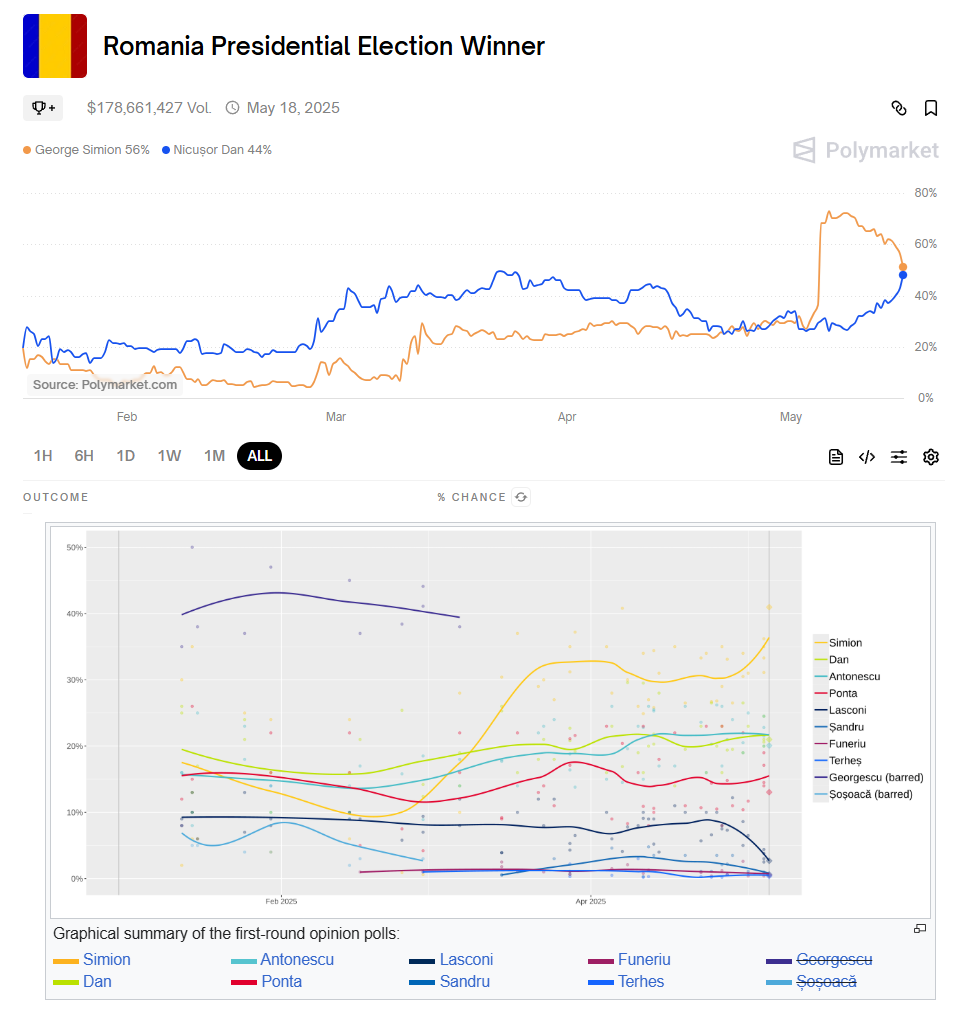

Last year’s Romanian presidential election illustrates the limitations of the betting market. A month before the first round of the election (May 4), Polymarket gave Nicușor Dan a 39% chance of winning and George Simion a 29.5% chance. Seems accurate, right? However, when Simion finished first by a large margin in the first round, his odds quickly overtook those of Dan’s. Between the two rounds, Simion’s odds were already above 70% and stayed above 50% until election day. Dan ultimately won the election by a relatively large margin in the second round.

Once again, opinion polls were more accurate than Polymarket: before the first round, most polls indicated Simion’s lead and predicted his percentage of the vote relatively accurately. However, most researchers were wrong about who Simion’s opponent would be, as they underestimated Dan and overestimated the support for Crin Antonescu and Viktor Ponta, who ultimately came in third and fourth. Polls conducted between the two rounds predicted a 50-50 split between Simion and Dan.

The election reveals one of the main issues with betting markets:

bettors, who are primarily interested in making money, are susceptible to hype and react sensitively to spectacular trends, such as the surprise rise of a previously disadvantaged candidate. In such cases, the pendulum can easily swing too far in the other direction.

This is interestingly the same problem that pollsters face: it is most difficult to measure support for candidates whose popularity suddenly plummets or soars; thus, they are often underestimated or overestimated.

So, what does this mean for the Hungarian elections?

The Polymarket curve for the Hungarian election currently most closely resembles the curve for two slightly right-leaning American swing states, Georgia and Arizona. In these states, Polymarket slightly favored Trump throughout the campaign, which proved to be accurate.

However, considering the fact that Polymarket is now unavailable in Hungary, and that the site’s user base is mostly American and Canadian, it is likely that the majority of money bet on the Hungarian election also comes from foreigners.

This means that bettors are not tapping into the public mood, but merely following news from international media – such as reports on opinion polls.

Moreover, foreign bettors are unlikely to be familiar with the Hungarian electoral system. This could be an issue if the gap between the two major parties closes and Tisza’s lead falls below 4–5%.

With repeatedly gerrymandered borders, electoral districts skew heavily to Fidesz, making it quite possible that even if Tisza wins the popular vote by multiple percentage points, Fidesz still wins more seats and thus the election. Foreign bettors may not consider such an outcome as they look at opinion polls, which still indicate Tisza’s lead.

Written and translated by Zalán Zubor. The original Hungarian version can be found here. Cover image: montage by Átlátszó