The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Streetlight scandal: identical calls for bids, same companies, always the same winner

Eger’s municipal government had planned a modernization of its public lighting system for HUF 7.4 billion through a bizarre construction, but the council ultimately did not support the decision. During the council meeting, they found that the tender seemed to restrict competition, the lowest bid was excluded, and two companies likely submitted fake bids. Eger’s tender drew attention to 15 other invitation-only procedures, raising suspicions of circumventing the procurement system. The city council did not approve the proposal by the independent (former Jobbik) mayor, Ádám Mirkóczi, so there is currently no funding available for the modernization of Eger’s public lighting.

The Eger city council decided last year to modernize the city’s streetlights. One of the first steps was to initiate an open procurement procedure – the “Modernization of Public Lighting” – following approval by the Municipal Procurement Decision-Making Committee (ÖKDB). Hope, then, for potential bidders – until it became clear that any hope was moot.

Suitable for Restricted Competition

The task was defined as follows: “modernization, maintenance, and operation of the active elements of the public lighting system within the framework of a service mixed with construction.” The project aimed to modernize 6,460 lamp fixtures and maintain an additional 250 lamps for 144 months, or 12 years.

However, the municipality specified two conditions in the tender that almost reduced the number of potential bidders to zero.

One requirement stated that “the contracting authority requires the establishment of a project company in this public procurement procedure.” According to an expert, this involves a lot of additional administrative work, which in itself may deter many bidders.

Even more problematic: the bidder is ineligible if they cannot provide a specific reference to a complex public lighting service – including design, execution, and operation of at least 1,300 lighting fixtures – within the past three years, counting from the submission of the tender, and no older than six years before the submission. The condition eliminated almost any competition because few companies satisfy the criterion.

“The second requirement excluded 99% of the market,” the expert said, “because it wasn’t enough to prove that the applicants had experience in lighting construction and maintenance; rather, it had to be demonstrated precisely within a financial and legal framework as prescribed by the municipality.

Atypical business model

The concept envisioned by the Eger municipality, the so-called ESCO financing, wouldn’t be a new idea in itself. The essence of this model is that the contractor advances the investment cost, which the municipality later repays gradually.

The winning company would have to establish a new LLC for the implementation, operation, and maintenance of the investment. The Eger municipality would acquire 100% ownership of this LLC over 12 years, transferring 1/12 of the ownership each year.

This idea is foreign to Hungary, but it is also a novel concept for Europe.

So atypical was the proposal that during the process, a dispute resolution request was submitted, in which an unnamed company argued that this inherently excludes state-owned enterprises from competition, since they cannot independently establish and sell companies. The dispute resolution request threatened that if the city did not withdraw the allegedly restrictive call for proposals, the company would appeal to the Procurement Review Board for remedy.

The municipality rejected the request, citing, among other reasons, that before issuing the tender, market research was conducted, revealing that at least 3 different companies in Hungary employ a solution that would meet the requirements of the call. Additionally, the process was an open procedure, extending to the entire European Union. Moreover, the necessary state permits for company formation are still obtainable.

We asked the leadership of the city of Eger to name the companies that, according to their surveys, have the necessary references. Additionally, we requested them to provide us with the documentation of the preliminary market research. However, the municipality declined this request, citing business confidentiality.

The estimated price would have been three times higher than the winning bid

More red flags started cropping up soon after. One of the applicants, DML Hungary Kft., was excluded on the grounds of offering an unreasonably low price, which they allegedly failed to justify adequately. Even after lengthy adjudication, DML Hungary was excluded from the competition. They submitted the lowest bid, at HUF 1.6 billion, while the other three bidding companies put in significantly more.

- Grep ESG Kft.: 7.4 billion HUF

- Vill-Attila Kft.: 7.9 billion HUF

- Megavolt Bt.: 8.3 billion HUF

Ultimately, DML Hungary’s bid was declared invalid because the company allegedly failed to adequately demonstrate that they “have a minimum of 12 months of professional experience in executing public lighting projects and did not respond to the request for supplementation.”

Then, more problems – the modernization of public lighting ended up costing HUF 7.4 billion instead of the estimated HUF 2.5 billion after Grep ESG Kft won the bid.

Fictitious bids?

Suspicions of overpricing weren’t the only concern raised by the tender. As we mentioned, alongside Grep ESG and DML Hungary, Megavolt Bt. and Vill-Attila Kft. also submitted bids – but Eger only examined the cheapest bids.

It’s not particularly surprising if we look at the background of these two companies. Megavolt Bt. had an annual revenue of only HUF 56.9 million in 2022, while Vill-Attila, founded in 2020, had just HUF 14.9 million

The combined revenue of these two companies over the past five years did not match the amounts stated in their respective bids.

Neither of them has won a public procurement independently. However, Vill-Attila has appeared as a subcontractor under the Grep Zrt., which nearly won the Eger tender, during the modernization of public lighting in Lajosmizse.

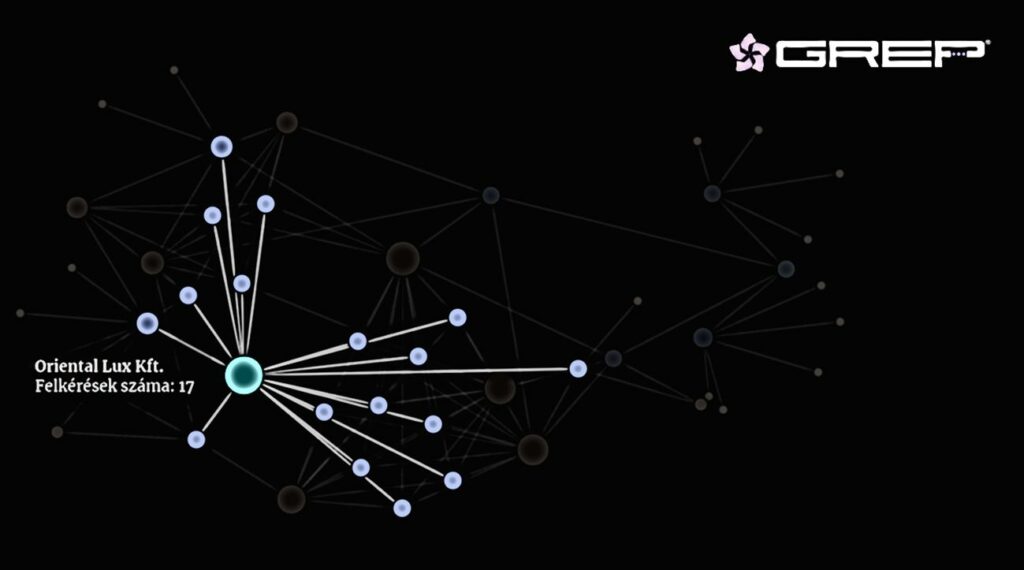

This wasn’t the only occasion where Vill-Attila participated in invitation-only tenders where Grep Zrt., or another company owned by the owners of Grep, Oriental Lux, emerged as the winner.

A pattern emerges…

Nine different municipalities invited bids from the same five companies in a search for a contractor to upgrade their street lighting. The winner was the same in each case, as in five other municipalities, where only four firms were identical. In 15 cases, the wording of the calls for tenders was almost the same word for word, and there were cases where the value of the tenders was only a few thousand forints below the threshold of HUF 300 million, dictated by KBT 115. We have reported these cases, which concern a breach of fair competition, to the authorities with Transparency International Hungary.

The Eger municipality’s tender for the modernisation of street lighting was unsuccessful after the body of representatives did not vote to commit HUF 7.5 billion from the 2025-2037 budgets over several years to cover the cost. The winner of the public procurement procedure would have been Grep ESG Ltd, whose ultimate owner is the Makra family – who also own GREP Green Public Lighting Zrt. (Grep Zrt.) and Oriental Lux Kft.

The pattern was a red flag for Transparency International, who had been investigating corruption in Hungary when they noticed that two companies, Grep Zrt. and Oriental Lux, had been successful almost exclusively in tenders under KBT 115 in recent years. In 21 of the 23 procedures won by the two companies since 2019, the contracting authority has chosen this type of contract,

with a total net value of the contracts reaching HUF 3.4 billion.

In nine out of 17 of Oriental Lux’s 115 procedures, the same firms were invited to tender by municipalities that were, hypothetically, independent of each other. In five other cases, four firms were always the same, and only one firm changed. In 15 cases, the wording of the calls was almost identical.

The firm Best Vill. 2000 Kft had been invited ten times to submit counter bids against Oriental Lux, but they never did. They did, however, work as a subcontractor for Grep Zrt. and Oriental Lux several times.

In three tenders, the value of the contract almost reached the threshold of HUF 300 million for the procedure, set by Article 115 of the Public Procurement Act.

All this is eerily similar to the KBT 115 procedures reported in the autumn, where the Public Procurement Authority had initiated legal procedures.

Repeat Offenders

Looking at the tenders one by one, it turned out that the municipalities of Jászapáti, Nyírmada, Nyírtelek, Nyírbogát, Nagyhalász, Jánkmajtis, Kocsord, Vaja and Sajókaza had, by coincidence, invited the same five companies to bid for the street lighting modernisation:

- Vill-Attila Ltd

- Gál-Munka Ltd

- Fényhozam Ltd.,

- Best-Vill.2000 Ltd.

- Oriental Lux Ltd.

Oriental Lux won every tender. Of the five companies invited, Fényhozam Ltd. submitted four bids, Vill-Attila Ltd. submitted one bid, and Best-Vill and Gál-Munka submitted none. One could speculate that there might have been a common contracting authority inviting the same companies, but the municipalities – all but one – procured the contracts themselves.

Since the only commonality in the tenders seems to be the winning bidder – Oriental Lux – there is suspicion that the company influenced the other bidders, too.

A similar phenomenon was observed in five other cases, where four of the invited firms were always identical.

Here, the constant players were

- DIV Lighting Ltd,

- Fényforrás Kft.,

- Lightning Ltd.

- Oriental Lux.

These tenders, however, had a joint operator in AppTender Application Development and Tender Consultancy Ltd. The Budaörs-based company has previously carried out procedures for the Hungarian Football Association and Északerdő Erdőgazdasági Zrt.

Vill-Attila Kft was a competitor of Grep ESG in the Eger tender, but it was also invited to bid in the second winning tender of Grep Zrt and the tenth winning tender of Oriental Lux. It was subcontracted to Grep Zrt for the modernisation of street lighting in Lajosmizse.

The owner of Fényforrás Kft in Litéri is Zoltán Pápai, who was also the owner of Fényhozam Kft in Tarpa. The latter was called to bid 12 times against Oriental Lux and twice against Grep Zrt. In total, he submitted bids six times, but he never won.

Gál-Munka és Tűzvédelmi Kft of Esztergom was invited 11 times to bid against Oriental Lux and once against Grep Zrt Best-Vill.2000 Ltd did not even try, despite being invited to bid ten times against Oriental Lux. Unsurprising, given that the company is also a subcontractor of Oriental Lux and Grep Zrt (see the Hort or Gyöngyös street lighting projects).

DIV Lighting Ltd, invited six times, is presumably out of the picture because it is undergoing liquidation. Villámszer Kft., which was also invited to bid on six occasions, was similarly inactive.

It is particularly interesting to note that the tenders of Diósd, Füzesabony and Jászapáti amounted to HUF 299.9 million: HUF 26,890 in one case, HUF 370,710 in another case.

In one case, the bid was only HUF 6516 below the HUF 300 million threshold.

This is the threshold for launching a restricted procedure under KBT 115 – anything above this must be submitted as an open procedure.

So, the company names were on repeat. But it wasn’t the only thing that was a recurring pattern – the wording of the call for tenders was also eerily similar – identical, even. We asked nine municipalities to tell us why they think the text was so similar – to no avail. They did not respond.

Details revealed at a board meeting

Perhaps part of the explanation can be found in the minutes recorded in 2020 in Jászszentandrás. At the invitation of Mayor Bálint Kolláth (Fidesz), Attila Makra, one of the owners of Oriental Lux and Grep Zrt., attended a municipal council meeting where he explained how ESCO financing works and why it is a good choice for the municipality.

According to the minutes, Mr Makra said: “If the board thinks it’s workable, the contract would be terminated and the annual notice period would expire, and in the meantime, you could start looking for a procurement consultant. We usually recommend three consultants to municipalities who deal with such investments. We don’t care which one the municipality chooses – they will carry out the procurement, which will have to be brought before the board anyway, which will have to be decided by the board again. Then the public procurement is launched, which takes a month and a half in a good case, three months or more in a bad case scenario. Once this is done, the contract is signed (…) As for the construction, we usually work with a local contractor, who also does the construction (…)

After all, that’s the way it goes.”

The council did indeed decide to terminate the existing contract at the next meeting, but what happened afterwards is unknown. A post appeared on the municipality’s Facebook page on July 21, 2022, stating, “I signed the modernization of public lighting today, so new, modern LED light sources will be installed throughout the settlement even this year.”

The signatory of the contract and the counterparty are not mentioned, and there is no trace of this in the minutes of the council meetings preceding or following the announcement. However, according to our information, the municipality eventually entered into agreements with two other companies instead of Makra’s company.

It is easily possible that the attractive financing solution (i.e., the ability for municipalities to pay for the investment in instalments rather than all at once) is appealing to many local governments, and the opportunity could be spread by word of mouth among municipal leaders.

The Legacy of the Elios Case

The real winners: Grep Zrt. and Oriental Lux. How, though, are they so efficient? If we were to be unkind, we could say they may have learned the methods from Elios.

The annual revenue of Grep Zrt. ranged between HUF 312 and 938 million in recent years. Oriental Lux’s went from HUF zero to 215 million in five years, and the value of its invested assets increased from HUF zero to 1.3 billion.

The name Grep Zrt. appeared in the OLAF report that addressed the Elios company’s public lighting scandal. As reported by our newspaper in 2018, Grep Kft. and Grep Green Zrt. were mentioned five times in the procurement database alongside Elios: once as consortium partners (for public lighting renovation in Paks) and four times as unsuccessful bidders.

The OLAF report also noted that Grep submitted a competitive bid in Mezőhegyes while they were aware of the exclusive offer given by Tungsram-Schreder to Elios.

The investigators in Brussels also took notice of the project in Hévíz, where both Grep and Polar Studió from Kecskemét submitted bids that exceeded Elios’s offer by the same percentage in 48 budget items: seven and nine percent, respectively. According to OLAF, all of this raised suspicions of fraud and document forgery.

“The Hungarian taxpayers pay the price twice for the Elios case because none of the actors were held accountable by the authorities. Firstly, it cost them HUF 13 billion when the Hungarian government chose reimbursement of EU funds instead of investigating the cases. Then, they suffer further damage as the implicated economic players continue their activities unpunished, as shown in the presented examples,” emphasized Judit Zeisler, project manager of TI Hungary.

Therefore, the civil organization intends to take legal action in the matter and requests investigations by the authorities regarding the presented phenomena.

We reached out to the owners of Grep Zrt. and Oriental Lux to respond to the descriptions in the articles, but the companies did not reply.

Translated by Vanda Mayer. The original, more detailed Hungarian version of this story was written by Eszter Katus and can be found here and here.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!