The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

This is how the Hungarian government is dealing with the energy crisis

In July 2022, the government declared an energy emergency and adopted a seven-point action plan to avert it. Since then, more than half a year has passed, so we had a look at how the government’s decision has been implemented. Let’s see the seven points one by one.

1. Maintaining low gas and electricity prices for households

This is immediately a point that has not been achieved. In fact, barely a week after the adoption of the energy emergency decree, the government significantly increased the residential gas and electricity tariffs above the average consumption level: the increase was almost double for electricity and seven and a half times for gas.

The announced increase in tariffs has also made firewood more expensive, by an average of almost 60% over the past year, according to the Central Statistical Office. In Hungary, more than 1.1 million people live in homes that are heated by firewood.

However, Hungarian gas and electricity prices are still rather low by European standards. In the chart below, Hungarian prices are marked in red: one is the reduced price, one is the price paid by a household with an annual consumption of 20% more than the average, and one is the average price paid by a household with an annual consumption of twice the average.

Certainly, many Hungarian households are struggling to pay the bills, but that is because Hungary is unfortunately among the member states with the lowest average income level.

These two points are treated as one, because in Hungary lignite is only burnt in the Mátra Power Plant in large quantities. The power plant was built in the 1960s, it is amortized, old, has high maintenance costs, and therefore, it has a high number of breakdowns. In such cases, the failed unit has to be shut down, a situation that occurred several times last year as well. Partly because of this, the Mátra Power Plant is producing less and less electricity. If the power plant’s production decreases, the demand for lignite decreases as well.

The upscaling of the production faces some major obstacles, e.g. such as the rising price of CO2. The Mátra Power Plant is the largest carbon emitter in Hungary. According to the company’s annual reports, the power plant already paid 59 billion forints for the quotas in 2021. The figure for 2022 is not yet available, but given last year’s trend in quota prices, a cost of up to HUF 80-120 billion would not be surprising. In other words, it is becoming more and more expensive every year for the power plant to produce electricity – and the more it wants to produce, the more carbon quotas it would have to buy.

Therefore, the plan all along the previous years has been to convert the plant by 2025, i.e. the time until the units have a licence to operate. The old lignite units were planned to be replaced with a 500 MW gas-fired power plant, a 31 MW plant burning waste and biomass, and a 200 MW solar power plant on the site of the closed and recultivated lignite mines. In April 2022, the project was classified as a priority investment. At the moment, it is rather unclear, how and when the project will progress.

4. Increasing the domestic gas production from 1.5 to 2 billion cubic metres

The amount of natural gas extracted in Hungary is decreasing year by year, and in 2022 it was still just over 1.5 billion cubic metres. However, even if we manage to reach 2 bcm of domestic production, i.e. slightly increase the lower band on the chart, we would still have 8-9 bcm of gas left to import. So this is hardly the magic bullet that will save Hungary from the energy crisis.

Although the Ministry of Energy has recently announced that production has been started at a new gas field in Békés county, in fact only exploratory drilling and test production has been carried out so far. Besides, there are many questions about the project that is taking place at an accelerated pace and with simplified regulations. The extraction of an ‘unconventional’ gas field may have serious environmental impacts, which, in the absence of adequate permits and impact assessment, are currently unknown to the Hungarian society.

5. Extension of the Paks Nuclear Power Plant’s lifetime

First, as the reactors’ licences will not expire until 2032-37, a future extension of the power palnt’s lifetime will obviously not provide any answer to the current crisis.

Secondly, the Paks NPP has already reached the end of its lifetime and has already been extended by 20 years. A further extension would mean that these reactors could be operated for 60 to 70 years instead of the originally planned 30 years. In other words, reactors designed in the 1970s to Soviet safety standards could be in operation in Hungary well into the 2050s.

This is a frightening prospect, especially in the light of the fact that a few years ago geological studies revealed that a fault line under the Paks site has been found, which makes it questionable whether the site is actually suitable for a nuclear power plant. At the time, Átlátszó found out that this fact had been concealed from the authorities during the licensing procedures for the new Paks II NPP, as the investor (MVM Paks II Zrt.) did not properly include the data in the documents submitted to the authorities. Now that the existence of the active fault has come to light, it should at least be taken into account before the government considers an extension of Paks NPP’s lifetime.

Paks II. NPP site does not comply with IAEA seismic safety recommendations – English

A tectonic fault line runs under the site of the planned Paks II nuclear plant in Hungary. Moreover, a geologist found traces of earthquakes that happened less than ten thousand years ago and reached the surface, right next to the site of the nuclear plant.

6. Storing the amount of natural gas necessary to secure the Hungarian natural gas supply for the next winter, up to the level of the transmission and storage capacities.

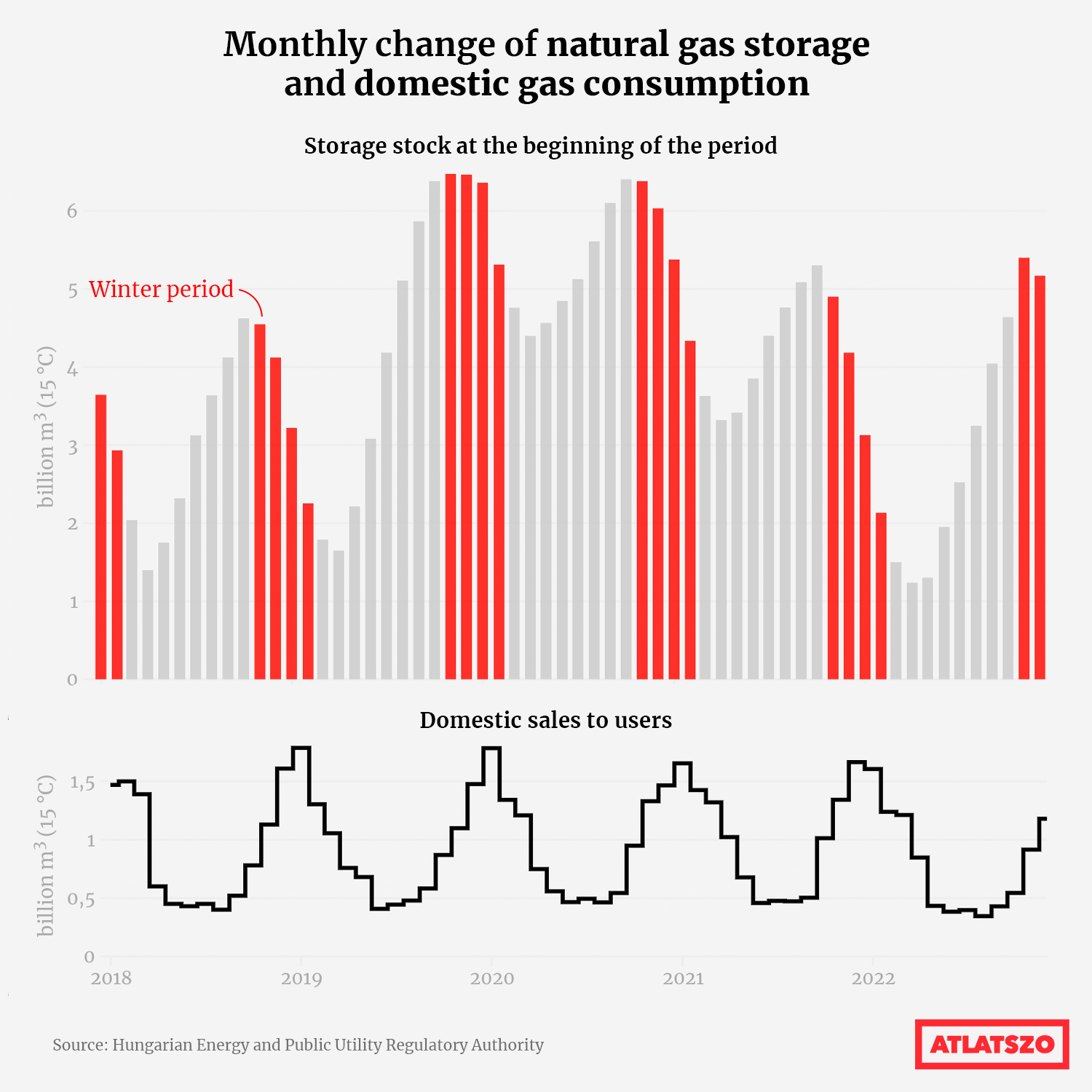

It is difficult to assess this point because it is challenging to understand what the writer was trying to say. Gas supply is not only covered from storages but also by continuous supply of gas through pipelines. We cannot rely on storage alone, because it can only accommodate about three quarters of the winter gas demand in Hungary. Therefore, it is difficult to know what level of storage the government would consider appropriate.

In Hungary, a total of 6.5 billion m3 of natural gas can be stored in storage facilities. In January this year, there were nearly 4 bcm in storage, but for example, January 2020 started with 6.3 bcm, while in January 2019 there was only 3.2 bcm gas stored. However, consumption in January in all three years was similar: 1.6-1.7 bcm. Thus, natural gas needs could be met at entirely different storage capacities.

Whatever the government may have wanted to say, since there are no supply disruptions in Hungary, let’s say that this point has been met so far.

7. Introduction of export restrictions on energy carriers

In a press release entitled “Another emergency measure: firewood exports from Hungary are banned“, the Ministry of Agriculture announced in August that “due to the war and the energy crisis caused by the Brussels sanctions, the government is imposing an export ban on energy carriers, including firewood.” However, in reality the government decree did not ban the export of firewood from Hungary. Exports must be notified previously and the Ministry of Agriculture may restrict them under certain – for us so far unknown – conditions. However, since the “export ban” was declared, it has not been restricted. According to data, some 90,000 tonnes of timber exports were reported to the department between August and the end of December, which the ministry appears to have authorised.

Prohibited, but still happening – Hungarian style ‘export ban’ on firewood – English

In a press release entitled “Another emergency measure: firewood exports from Hungary are banned”, the Ministry of Agriculture announced on 9 August that “due to the war and the energy crisis caused by the Brussels sanctions, the government is imposing an export ban on energy carriers, including firewood.”

Besides firewood, a similar government decree was adopted in September for coal products. However, in the months following the adoption of the decree allowing export restrictions, nearly 950 tonnes of lignite and 33,000 tonnes of coke were exported. The chart shows the data for the full year and for previous years:

As we can sum up, these seven points primarily serve communication purposes, and provide little substantive solution to the energy crisis, security of supply, or one the most significant challenge of our time, climate change.

Written and translated by Orsolya Fülöp. Hungarian version. Data visualisation: Krisztián Szabó. Cover photo: MTI.