The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Hungarians take to the streets to demonstrate for the future of education after decades of erosion

For weeks, students, parents, and teachers have been organizing demonstrations after five teachers were fired from Budapest’s Kolcsey Ferenc Gimnazium, allegedly for civil disobedience action. Hungarians have taken to the streets to protest poor living conditions for teachers and a failing education system.

Demonstrations were held across the country on October 5, 11, and 14. Teachers have also launched the “I Want to Teach” movement. In the most recent action on October 14, protestors formed kilometres-long human chains after the Democratic Union of Teachers (PDSZ) and the Teachers’ Union (PSZ) called for civil disobedience.

The crowd gathered in front of the Ministry of Interior and launched paper balls – made of the freely distributed pro-government Metropol newspaper – at a cardboard cut-out of Minister of Interior Sandor Pinter. They also burnt threatening letters sent to teachers. Many protestors wore checked shirts, harking back to the teachers’ demonstrations held in 2016.

A sad state of affairs

The ramp up – a series of pernicious government policies that gradually eroded the Hungarian public education system – has been decades-long. One of the cruxes of the problem is that the current teacher promotion model ties salaries to job performance appraisals – and the salaries are calculated with the 2014 minimum wage.

For any given teacher with a college degree and 18 to 20 years of experience, the government’s failure to adjust salaries in congruence with the rising minimum wage has seen them lose out on around 5.5 million HUF on average. This means any given teacher in Hungary has worked around 17 months without pay over a seven-year period, according to the PDSZ.

That teachers are grossly under-salaried becomes even clearer when the 2022 minimum wage is considered, which currently stands at 200,000 HUF annually. In comparison, the salary for an entry-level teacher with a college degree is 219,000 HUF.

In Hungary, teaching has become a minimum wage job.

And the country doesn’t save face on an international level, either. OECD data from 2021 found that Hungarian teachers’ average pay was 61 per cent of the average pay for other college graduates – a pitiful statistic, considering the EU average is 90.19 per cent and the OECD average is 90.42 per cent.

Average teacher salaries relative to earnings for tertiary-educated workers

Statistics about education spending as a percentage of GDP tell the same story – in 2019, Hungary ranked fourth from the bottom after falling behind in the 2010s when the government decided against increasing the proportion of education spending.

Poor pay and working conditions have, in turn, seen an exodus of over 15,000 teachers from the public education sector.

According to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH), the number of teachers in public education and professional training institutions dropped from 180k in 2001 to 164k in 2021. PDSZ president Tamas Totyik predicted last year that an additional 22k teachers could leave in the next five years. The teacher shortage has left schools desperately scrambling to fill positions – just days before the start of the school year, Atlatszo found 780 job postings for educators on the Public Sector Careers Portal.

As distressing as it is, the shortage is not shocking. Teaching, according to a 2021 PDSZ survey, has become an unviable source of living – over 97 per cent of the surveyed teachers reported significant financial difficulties. The PDSZ noted:

“The results show a completely impoverished class of people – a class circling absolute poverty. In today’s Hungary, that’s where our teachers are.”

The impact of this deleterious underfunding and subsequent brain drain has started to show in student results. Over the last 13 years, sixth graders’ average performances in math and reading comprehension has drastically declined. The slump has been most strongly felt in rural areas that were already struggling with increased deprivation. OECD data from the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) that shows Hungarian results lagging behind the EU average reflects the country’s educational backsliding.

The spark is lit

The failing public schools have created a brewing discontent with underfunding, but the mass demonstrations were triggered by the dismissal of five teachers from the Kolcsey Ferenc Gimnazium on September 30.

For months now, teachers have been participating in civil disobedience actions as a method of last resort to express their discontent with the public education system and poor living standards. It became a tool for protesting after their right to strike was essentially stripped by a February government decree.

In response, district school boards across the country have been issuing letters to teachers that warn against participation in these civil disobedience actions. In Miskolc, letters turned to action when the Vice Principal of the Herman Otto High School was released from his position in early September.

The school board claimed the five dismissals from the Ferenc Kolcsey Gimnazium were justified by repeated “unlawful actions”.

Demonstrations broke out on the evening of the dismissals when hundreds of people gathered in front of the VI district high school.

The movement gained momentum with a larger demonstration on October 5, when the crowd presented a statement to the Ministry of the Interior from the Kolcsey school’s 43 teachers. In addition to an online petition, the demonstrators also submitted a petition directly to the Ministry, calling on them to reinstate the fired teachers immediately.

Katalin Torley, one of the five dismissed teachers, received her letter by mail. While the founder of the “I Want to Teach” movement knew about the letter’s content in advance, a four-day delay in delivery meant she was not technically terminated until October 5. The waiting period left her in a state of heightened emotional distress. Her firing ended her 23-year teaching tenure at the Kolcsey Ferenc Gimnazium.

“We are teachers, and we will remain teachers. They can take our jobs, but they cannot take that away from us,” said Torley.

Demonstrating teacher Edit Simko noted: “Our colleagues were guilty of civil disobedience action that advocated for a better education system, while our district board of education has actively tried to destroy it.”

Tens of thousands gathered again on October 5 – World Teachers’ Day – after the PDSZ called for a nationwide strike. The protestors formed human chains that extended over several kilometres and occupied the downtown Margit Bridge, before they moved to the Parliament and the Kossuth Square.

Students, parents, and teachers across the country called for an immediate pay raise for teachers and improvements to the education system. They also demanded a right to strike for educators. Viktoria Walton, a member of a parents’ organization, dressed in all-black to address the crowd: “The Hungarian public education system is dead. It lived for 155 years,” she said.

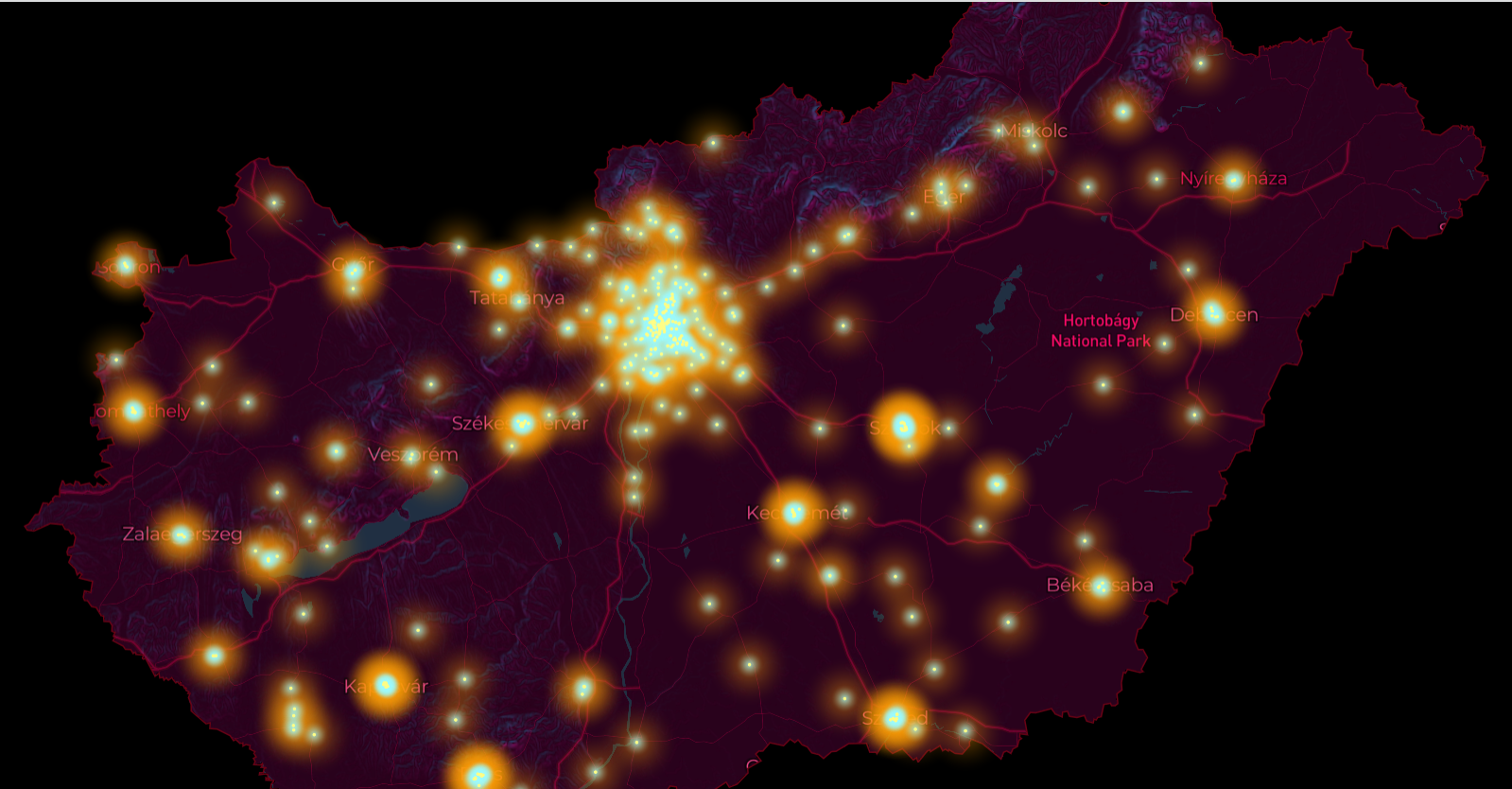

In a rare form of nationwide solidarity, the demonstrations also spread to other regions in the country. By October 11, Atlatszo counted 94 institutions across 48 settlements – in total, 2,137 people – that joined the protests.

Atlatszo has mapped the participation in the demonstrations here. The map includes institutions that have released public statements on Facebook, their official websites, or in the media. If you have any information about institutions that are participating, you can fill out this Google survey to complete our data.

The government responds – barely

In response to the demonstrations, Minister of the Prime Minister’s Office Gergely Gulyas announced in Thursday’s press conference that teacher salaries could increase by 21 per cent in 2023, 25 per cent in 2024, and 30 per cent in 2025 in comparison to the current rates. The aim, he said, is to drive teachers’ salaries to 80 per cent of the average college graduate salary by 2025.

But Gulyas failed to answer questions about teacher intimidation, and he denied that teachers were fired due to civil disobedience.

“I won’t speak about civil disobedience, because there’s no such thing right now,” said the Minister. He added that, in today’s Hungary, no one gets fired for lawfully participating in strikes.

Gulyas turned the issue into partisan politics when he accused Klara Dobrev and left-wing EP members of working against the teachers’ interests. Gulyas claimed that the opposition was actively blocking European Union funds to Hungary that would be necessary to finance a teacher salary increase. In reality, said Gulyas, the demonstrations are against Dobrev.

In the same press conference, he accused the EU of blackmail after they made funding conditional on the government’s anti-corruption reforms. Gulyas said that, if forced, the government will turn to alternative sources to ensure financial stability.

In a statement provided to Atlatszo, global union federation Education International (EI) expressed “full solidarity with Hungarian teachers and education personnel who are demanding decent salaries and better working conditions.”

They also supported the “I Want to Teach” campaign for the ILO-ensured fundamental human and trade union right to protest and strike. General Secretary of Education International David Edwards said: “At Education International, we fully support the thousands of Hungarian students and parents who have protested and rallied to support teachers.

“They clearly understand the key role educators play for a democratic, peaceful, and sustainable society and how important it is to trust teachers and respect their right to organize.”

Edwards added that EI “urges the Hungarian government to immediately engage through social dialogue with the organized, representative voice of education personnel and to find a solution to the current crisis.

“As our members in Hungary say in their demonstrations: ‘No teachers, no future’. We fully believe that all governments should trust, involve, and respect teachers,” he said. The next large demonstration is planned for October 23, when protestors will meet at Kalvin Square at 4pm. There will also be national strike day on October 27.

Written by Vanda Mayer, data visualisation: Zita Szopkó. Cover photo: The demonstration organised by students on 14 October. By Dénes Balogh / Atlatszo.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!