The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Water temperature exceeded the limit of 30°C in the Danube at the Paks NPP

Four years ago, and now again, we measured higher water temperatures in the Danube at the Paks Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) than the plant’s staff who monitor the water temperatures. Although the exceedance of the threshold was not acknowledged by the Paks nuclear power plant four years ago, our article in 2018 led them to publish how they measure the temperature of the Danube. Now, following the published method, we took measurements again on a hot August day. The law says that to protect aquatic life, the temperature of the Danube must not exceed 30 degrees Celsius anywhere at 500 metres from the entry point of the discharge canal of the Paks NPP, but our measurements showed that the river was warmer this time too. Stinky, yellowish foam on the surface of the water and hundreds of dead mussels on the shore greeted Atlatszo reporters on the spot.

At the end of July, Portfolio reported that the water level of the Danube at Paks is only about 70 centimetres above the lowest level ever recorded, and it is also extremely warm, and therefore the Paks NPP’s production had been reduced. Then, on 30 July, the overheating of the Danube caused the plant to be scaled down by 240 MW because one of the temperature readings was 29.67 °C, which exceeded the intervention limit of 29.5 °C set by the plant’s internal rules. The decrease of the production did not last long, however, as the plant was scaled up again the next day.

We then decided to carry out measurements in the heatwave again this year, based on the methodology published earlier.

Four years ago, in the summer of 2018, after Energiaklub asked for the official measurement data in vain, we measured water temperatures ourselves and found that it was above 30 degrees Celsius at several points in the Danube below the cooling water discharge canal of the Paks NPP. A few kilometres above the plant (to the north), the water was 25-26 degrees Celsius at the same time.

The Danube higher than 30 degrees Celsius again

We approached the nuclear power plant and the point for which the relevant legislation sets the water temperature limit, by a motorboat. The temperature limit is necessary because the Paks NPP discharges the cooling water taken from the Danube back into the river, only warmed up (the released water is about 33-35 degrees Celsius), and thus heats the whole river.

The legislation states quite precisely that

“the temperature of the receiving water shall not exceed 30°C at any point on the section at 500 metres downstream from the point of discharge”.

This should be measured at the section of the Danube of 1525.5 river km.

On the day of our measurement, Hungary had already been sweating in temperatures of around 30 degrees for a good two weeks, and a third-degree heat warning had been issued two days earlier.

We used a newly purchased TFA Dostmann digital thermometer with a sensor attached to a 1 kilo weight and sunk in the appropriate depth. We measured the water temperature at several points in the river section concerned, at depths of 50 and 150 cm, from a boat as well as while standing in the river, between 11 am and 3 pm.

Here’s what we found:

- at the 1525.5 river km section of the Danube, on the side of the NPP, near the shore, at a depth of 50 cm, we measured 30.8°C. At 150 cm depth, it was 30.5°C.

- In the middle of the Danube, 28.3-29°C were measured from the moving boat.

- Directly at the discharge canal of the power plant, values between 30 and 31.5°C were obtained, while on the other side of the Danube, oppsite to the power plant (East), the coastal waters measured 27.2°C in 50 cm depth.

- Several kilometres further south, but still on the west (NPP) side, the water was 29.2°C.

- Before arriving at the measurement point, a check measurement was also taken in the main channel on a “flat” section of the Danube, i.e. north of the power plant, where the impact of the power plant is not felt. Here we measured 25.5°C around 11:30 am.

- Meanwhile, the water temperatures published by the NPP on 5 August were 28.56°C (150 cm) and 28.81°C (50 cm).

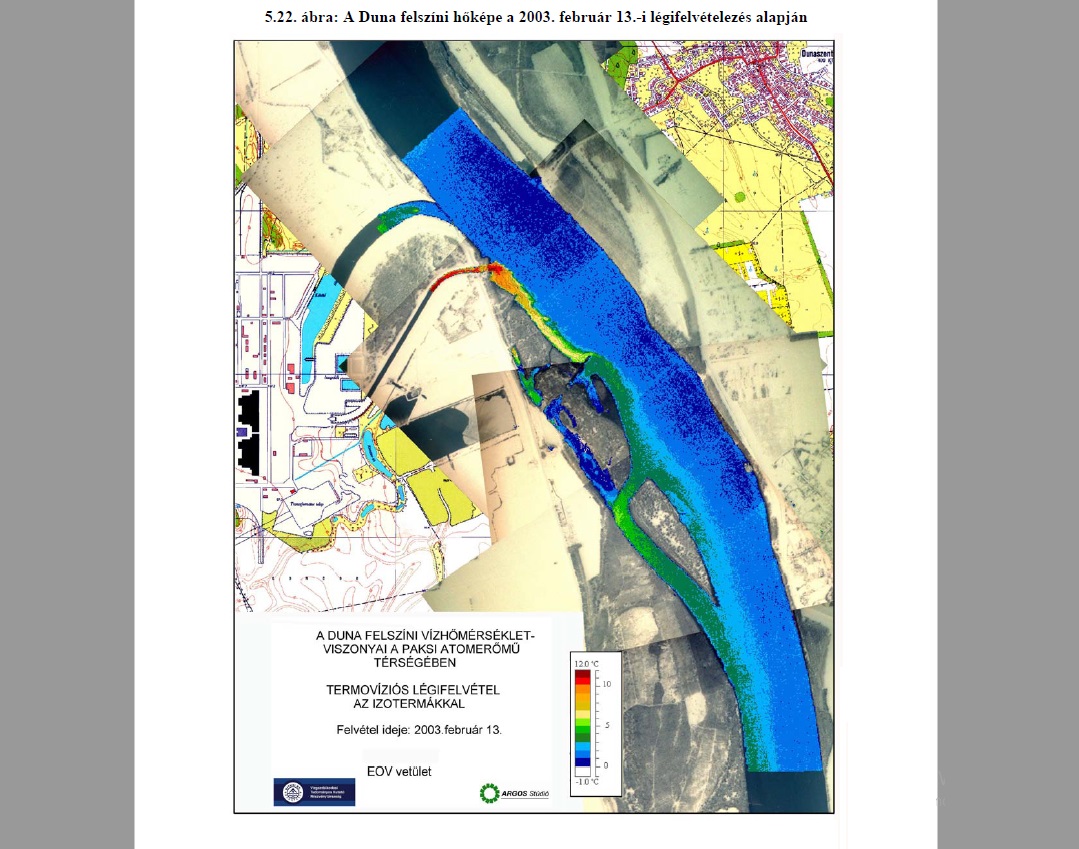

That our measurements may be accurate is confirmed by the details and thermal image (pages 79-80) of the study on the life-time extension of the Paks NPP. As they write: “The released hot water always moves down towards the right bank and penetrates the water areas between the reefs as well. Most of the discharged water mixes, in 95 %, between four and five km from the outlet canal. The discharged water could be traced, according to the surveys of summer 2002 and winter 2003, approximately to the Gerjen-Bátya line, which corresponds to about 10 river km from the outlet point.”

In other words, the warmest water may be found below the power plant, on the west side of the Danube, along the bank. Right where we measured 30.8 and 30.5 degrees Celsius at 50 and 150 cm depth.

According to the official data of the Ministry of Interior’s Directorate General for Water, the water temperature in Paks was 25.2 C at 11 and 12 am that day, measured at the 1531 river km.

Questions without answers

When we reached the discharge canal of the NPP, we noticed two things: firstly, the yellowish, smelly foam on the surface of the water, which we had not experienced before or afterwards in other river sections. Secondly, we saw a motorboat that had just docked at the canal. We assumed it was the Paks NPP’s measuring boat, which probably returned, shortly after 11:30 am, from taking temperatures.

In a previous request for data, we were told that the measurement is usually taking place between 11 am and 2 pm. However, we thought that the river might be warmer in the afternoon, so we waited a little and took additional measurements in the meantime.

When we returned to the measuring section at around 2 pm, we found a mass of empty shells on the bank and dead mussels floating past us in the water. This was another phenomenon we had not seen anywhere else. All this was captured on video.

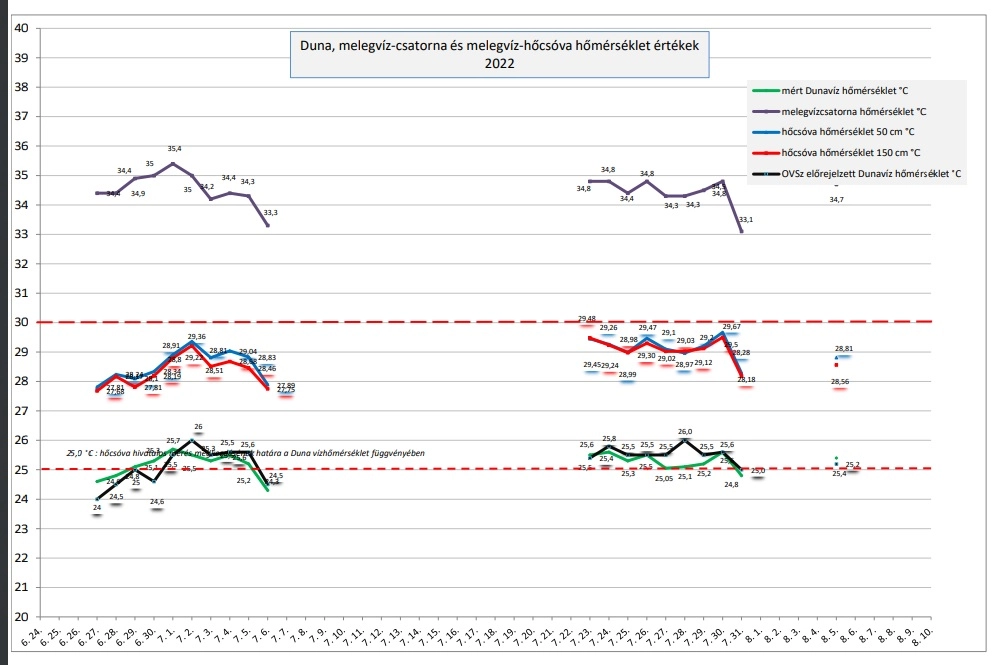

The nuclear power plant published their daily measurement data on the same day, which can be seen in the diagram below. The data in blue and red are the ones measured by the nuclear power plant during periods when the baseline Danube temperature is above 25°C.

It is clearly visible that the Danube temperature never reaches 30°C according to the measurements of the Paks NPP.

As our measurements show that the Danube temperature exceeded the permitted level at several points in the legally defined section, we believe that the plant’s method raises several questions:

- On the one hand, if the many recorded measurements end up forming one single daily value, there may be some measurements above 30 degrees which will be compensated by the other values below 30 degrees. However, this contradicts the legislation, according to which if a single point is measured at 30 degrees, it is considered as an exceedance.

- On the other hand, according to the legislation, the Danube cannot be warmer than 30 degrees Celsius at any point, e.g. at a depth of 30 cm either, but this is not measured.

- Moreover, according to the NPP itself, it is precisely in the hottest part of the Danube that is not measured, because “the immediate area near the shore (approx. 0-25 m) cannot be monitored for technical reasons of measurement from a boat”.

- Furthermore, it is also possible that different results would be obtained at later times on a given day as the river temperature is warmer in the evening than in the morning.

This is apparently confirmed by the official water temperature data which shows that on none of the selected days was the Danube warmest between 11am and 2pm (when the nuclear power plant carries out the measurements), but later: on August 1 at 6pm, on August 2 at 7pm, on August 3 at 7pm and 8pm, on August 4 at 7pm and 9pm, and on August 5, when we visited Paks, at 9pm. That is, presumably, we would have measured temperatures higher than 30.8 C in the evening hours.

We made significant efforts to consult with several experts about the measurement methodology. First of all, we wanted to ask the Department of Sanitary and Environmental Engineering of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, that, in a 2010 study, proposed the measurement method currently used by the Paks NPP. Unfortunately, however, citing the restrictions of the research contracts with the nuclear power plant and the obligation of confidentiality, the University did not answer our questions. They, however, claimed that

“the subject (e.g. a potential review of the methodology) is of scientific interest and of great environmental importance”.

Besides, we approached the Hungarian Hydrological Society, the Széchenyi University’s Department of Transport Infrastructure and Water Resources Engineering, the Water Management Section of the Hungarian Chamber of Engineers, the North-Transdanubian Water Directorate, but none of them provided a response to our question for various reasons.

We contacted the relevant environmental authority as well to find out how they monitor compliance with the legal threshold. We asked the Government Offices of Baranya County and Tolna County when and how they checked the NPP’s own water temperature measurements in the last five years, and whether the NPP’s data were correct. We also asked whether there had been any cases of irregularities and, if so, what the consequences were. In response to our request for public data, they replied that “the measurement of the water temperature of the Danube and the provision of related reports to the Baranya County Government Office is carried out in accordance with the legislation and the Paks NPP’s Licence, and

the Baranya County Government Office has not detected any cases of irregularities.”

However, no further details were provided.

We also contacted the Paks NPP, but we did not receive any response from them.

On the trail of dead mussels

We also wrote an email to the Centre for Ecological Research of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, hoping that the Institute of Aquatic Ecology can provide answers to the question of what damage 30 degrees Celsius causes to the Danube’s ecosystem and what the ideal temperature range would be. However, they had not responded by the time of publication of this article.

But in a 2019 article, they wrote that the effects of global warming on the Danube are already being felt today: changes in the seasonal distribution of water yields and a gradual rise in water temperature are affecting the river’s ecosystem, from the smallest microbes through millimetre-long aquatic invertebrates, to the largest fish, up to several metres long.

Hundreds of mussel shells litter the Danube bank below the Paks nuclear power plant on the western side of the measurement section.

In relation to the dead mussels, hydrobiologist Béla Csányi told Átlátszó that “in general, during the summer season, there is a selective mortality of Chinese pond mussels (also known as amur mussels, Latin: Sinanodonta woodiana) along the Danube, caused by a species-specific disease. (….) The heated cooling water from the Paks NPP may of course contribute to this.”

First experienced twenty years ago

The high temperature water emitted by the NPP has long been the subject of investigations. In its 2006 environmental permit, the South Transdanubian Environment, Nature and Water Inspectorate states, among other things (page 36), that the observations on the plant’s operation show that the impact on aquatic life is inconclusive.

We have visited this section (from page 81), which describes the impact of the hot water from the Paks nuclear power plant on the Danube’s ecosystem, based on the results of field investigations.

It describes the biological consequences as “two types of effects:

– the sudden onset of temperature stress, which affects mainly planktonic organisms (bacteria, algae, roundworms, planktonic crustaceans, fish larvae) passing directly through the cooling system of the plant, and

– the thermal effect in the heat flux, affecting both sediment- and coating-dwelling macroscopic invertebrates (worms, snails, mussels, aquatic insect larvae) and passively drifting (plankton) and actively swimming (fish) organisms that are mixed with the hot water.”

The studies show that the impact of the hot water discharged by the Paks NPP is not significant for fish, but significant for macroscopic invertebrates, with the recovery of the original fauna only starting with the decrease in water temperature (around 500 m below the hot water discharge).

From an ecological point of view, however, the greatest threat could be if “under warm-water conditions, newly introduced or introduced species begin to reproduce rapidly and displace native species with similar ecological needs by spreading rapidly,” the document says.

Drought is a real risk

This is particularly important in the light of the problems caused by drought and overheating of rivers around power plants in many European countries this summer. In France, several nuclear power plants had to impose significant power cuts during July and August because the surrounding rivers exceeded the permitted temperatures of 26, 28 or 30 degrees Celsius.

The drought in Hungary this year has caused drying up of lakes and streams, low water levels in major rivers and a loss of production value in agriculture of around HUF 1200 billion so far.

Written by Orsolya Fülöp and Eszter Katus, translated by Orsolya Fülöp. Photography and video by Dénes Balogh. The Hungarian version of this story is available here.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!