The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Enemy of the State: Branded as Foreign Agent in Putin’s Russia

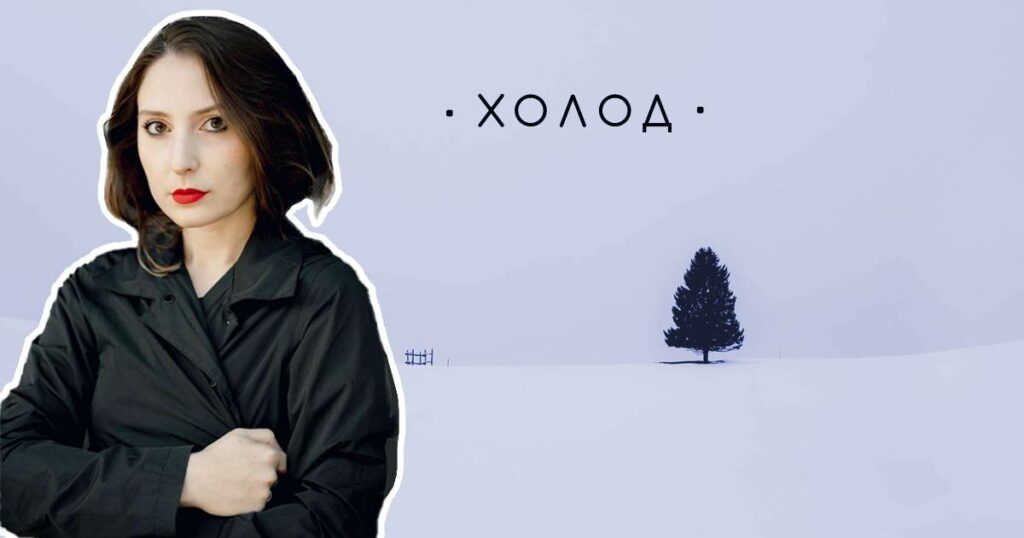

When Moscow branded journalist Taisia Bekbulatova as “foreign agent”, it was more than a bureaucratic label. It was a declaration of war against her profession. From exile, Bekbulatova continues to run Holod Media, reaching millions inside Russia despite censorship. Our other interviewee is a lawyer who asked that her name be withheld, because she works to defend journalists navigating a legal system designed to cancel them. Our interview was conducted at the International Journalism Forum conference in Athens.

Taisia Bekbulatova is a Russian journalist and the founder of Holod Media, an independent outlet known for its in-depth regional reporting. Declared a “foreign agent” in 2021, she left Russia under pressure and now works in exile from Germany, continuing to reach audiences inside Russia despite censorship. Our other interviewee, a lawyer who requested anyonymity, has spent decades defending journalists and outlets from censorship and persecution.

Please tell me your personal story. What do you do as a journalist, and how did you end up being labeled as a foreign agent?

TB: I’ve been a journalist all my life. I studied journalism at Moscow State University and began working when I was just 18. My first job was with Kommersant, one of Russia’s leading newspapers. Later, I joined Meduza as a special correspondent. In 2019, I founded Holod Media, an independent outlet focusing on long-form stories from Russia’s regions. I was both founder and editor-in-chief. We covered regional life, social issues, and the failures of the state—stories of crime, violence, and corruption. For instance, one of our first investigations was about a serial killer who raped and murdered women. Despite victims and witnesses reporting him to officials, the authorities ignored the complaints. Because of this neglect, he was able to continue for years. Officially, at least ten women were killed or assaulted. In 2021, I was declared a foreign agent because Holod was independent and critical of the state. I did not want that label, but the authorities imposed it.

Did they give you any reasons? For example, did it have to do something with foreign funding?

TB: The explanation was vague. They pointed to me sharing Meduza articles and receiving money from abroad. We didn’t receive money illegally. But the law kept changing and tightening, making it easier for them to declare anyone a foreign agent. Essentially, they just needed a pretext.

Was your website also blocked after you being labeled a foreign agent?

TB: The website was blocked in 2022, right after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Shortly after, Holod itself was added to the list of foreign agents, in addition to me personally. Both I and my outlet were branded enemies of the state.

What exactly does being declared a foreign agent mean in practical terms?

TB: By law, any statement I make must carry a disclaimer: “This material was produced by a foreign agent.” It applies even to reposts of other people’s words. The idea is to brand you publicly as untrustworthy, as an “enemy of the state.” Even if your website is blocked, you must still include the disclaimer, since people can read it with a VPN. I refuse to comply, so the state fines me regularly.

Why did you choose not to comply?

TB: Because I am not a foreign agent. I love my country, and I find the label humiliating. It alienates you from your audience. Many colleagues comply because they have more to lose: family in Russia, assets, or the possibility of returning someday.

Are there others who also refuse?

TB: Yes, many. Some tried to comply, but it didn’t help—they were still declared extremists or faced new charges. The law is arbitrary, some people eventually give up complying. It feels pointless.

Anonymous lawyer: Compliance is often just a survival tactic. People comply not because they respect the law, but to minimize personal risk. Some have elderly parents or children in Russia. Others want to avoid being placed on international wanted lists. Even if Interpol says it won’t honor Russia’s politically motivated warrants, that could change. And bilateral agreements with countries like Turkey or Serbia create risks. Journalists can be arrested abroad at Russia’s request.

So you refused to comply. What happened after that?

TB: I started receiving fines. Just two unpaid fines can lead to criminal charges. I already have several.

Are you still based in Russia?

TB: No, I cannot return.

Have they pressed criminal charges?

TB: Not yet, but they could. Sometimes people don’t even know until they appear on a wanted list. With the number of fines I’ve received, charges are always possible.

When did you decide to leave?

TB: In 2021, after my apartment was searched as part of another investigation. Lawyers told me to leave temporarily. I never returned. In 2022, after the invasion, I went to Ukraine to report on Russian war crimes. That made returning impossible. I doubt they would forgive me for that.

Where do you live now?

TB: In Germany.

Do you still have family or assets in Russia?

TB: Yes, I have relatives and close friends there. We mainly communicate online, but it’s becoming harder. Authorities block messengers and VPNs. Recently, they restricted calls on Telegram and WhatsApp. For older people who aren’t tech-savvy, staying in touch is nearly impossible.

Were you prepared for this outcome when you started your independent outlet?

TB: No. Nobody was prepared.

AL: You cannot prepare for exile. You live a normal life as a respected professional, and suddenly you’re branded a national security threat. It’s a shock. Exile is not a voluntary migration; it is forced, and it destroys the life you planned.

TB: Everything changed so quickly. In 2019, we were still operating legally. We sold podcasts, partnered with platforms, grew our audience. There were already foreign agents and jailed journalists, but most media still functioned. Then things escalated rapidly. By 2022, nearly all independent outlets were exiled or banned. Overnight, we became criminals.

Did you think about quitting journalism to avoid conflict with the state?

TB: Constantly. But we can’t. Journalists and lawyers like us are stubborn people. This is our profession.

AL: Imagine training your whole life for a profession, excelling at it, and then being told it is now criminal. Your choices are limited: stay silent, risk persecution, or abandon your career. Some people gave up and took other jobs—caretakers, plumbers, anything. But for many, abandoning journalism or law means abandoning who you are. Continuing is risky, but it is the only way to remain true to yourself.

Once you are labeled a foreign agent, can you ever be removed from the blacklist?

AL: Almost never. A handful have managed, but only by quitting their profession completely and living in silence. It’s essentially a hostage situation: either silence yourself, or live in exile under threat forever.

What methods are used against journalists abroad?

TB: There have been suspected poisonings. Hard to prove, but several colleagues believe they were targeted. Beyond that, the state uses legal tools. If your passport expires while you face charges, you might not get a new one, leaving you trapped. It sounds minor, but being undocumented can ruin your life.

Can exiled journalists apply for asylum in Europe?

TB: In some countries, yes, but it depends on proof. Many struggle to demonstrate they are individually targeted. Meanwhile, we remain tied to Russia through bank accounts, legal documents, and obligations.

AL: Even giving up citizenship doesn’t help. Some foreign agents never had Russian citizenship at all—they simply published in Russian. Authorities don’t care. Citizenship doesn’t protect you from harassment or surveillance. Russian authorities are wealthy, influential, and infiltrated into many countries. Risks abroad are real.

Why go after journalists in exile? Do you still have influence inside Russia?

TB: Yes. Around 80% of our audience is still in Russia. People use VPNs and creative methods to access our content. This is why the Russian authorities still treat independent media as a threat. If we had no audience, they wouldn’t bother.

AL: Research confirms this. Russians still want independent information. Propaganda is massive, funded on the scale of national budgets, but audiences for independent media remain strong and even grow. People avoid protests for safety, but privately they want to know the truth. Journalists find ways to deliver it: PDFs, podcasts, YouTube, Telegram. Demand persists.

Do people inside Russia still talk to you?

TB: Yes, but with difficulty. Fear makes many refuse. We often need to approach dozens to find one source willing to speak, especially about war.

AL: Authorities punish some sources, though mostly in extreme cases. There are real dangers. Novaya Gazeta Europe once published a story about a soldier killed in Ukraine. His mother and sister spoke on record. Both were later charged with “discrediting the army”. That case taught us to protect sources carefully—no names, no faces when possible.

TB: In Belarus, anonymity is even more extreme: everyone is anonymous—authors, experts, sources. It hurts audience trust, but safety demands it. Russian media may follow that path too.

What keeps you motivated?

TB: Responsibility. We’ve built an audience, and they rely on us. As long as we can reach people in Russia, we continue. If that ends, I would stop. I don’t want to publish only for the diaspora. The point is to inform those inside Russia.

Could this model spread internationally?

AL: Unfortunately, yes. Authoritarian states learn from each other. The “foreign agent” concept itself is not Russian—it comes from the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, originally about lobbying. Russia weaponized it against civil society. Similar laws exist in Israel, Australia, and elsewhere. The danger is that governments everywhere may use it to silence critics—journalists, NGOs, even artists. Unless there is international action, we will see this model spread, even in Europe.

Written and translated by Tamás Bodoky. The Hungarian version of this interview is here.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!