The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Danube warming up – Climate change, dead mussels and power plants turned down

According to my childhood memories, the Danube is cold. Even on scorching summer days, we’d wade into the water only knee-deep. These memories slowly begin to fade as sweaty summers see the water temperatures go up to 25 or 26°C. This is of course not only my personal experience: the warming is demonstrated by official measurements as well. Although beachgoers may rejoice, the warming and the increasing occurrence of extreme low water flows becomes more and more challenging for both the river’s wildlife and for the users of the Danube, i.e. mankind. This year, we dedicate March 22, the World Water Day to the Danube, in collaboration with Austria’s Der Standard.

The Danube, 2,857 kilometers long, drains the most international river basin on earth, shared by 19 countries. This cross-border nature causes numerous challenges for river management, also making data collection almost impossible. We spent months collecting temperature data, as even though a transnational body, the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR) exists, but is not allowed by law to release data of national authorities. Our data request to national authorities was unfortunately unsuccessful. Therefore we read hundreds of data from large print diagrams by hand, using a ruler, and then entered them into excel spreadsheets.

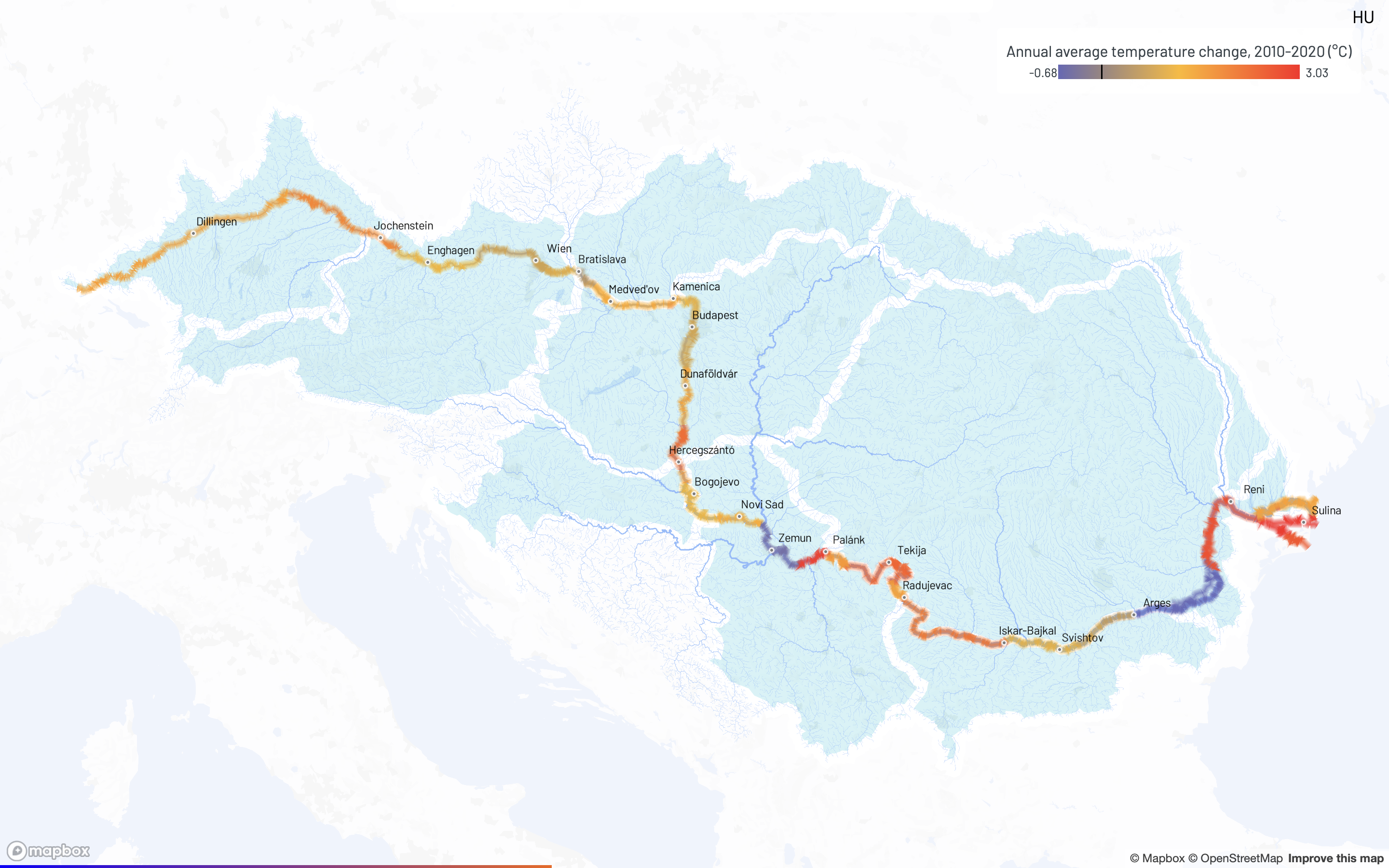

We then turned the data into a compelling data visualisation project that can be found on our dedicated subpage.

According to data, the Danube is getting warm

According to the Hungarian water authorities, in 1965 the average annual temperature of the Danube was 10.2 °C in Budapest and 9.9 °C in Paks. In 2022, the water was 3.5 °C warmer in both places. Although temperatures varied over the years, the increasing trend is clear. The problem is not unique to Hungary. A graph, published by the ICDPR in the Danube River Basin Management Plan, shows that temperatures have been rising from Kienstock, Germany to Novo Selo in Bulgaria by several degrees.

András Abonyi, a researcher at the Institute of Aquatic Ecology of the HUN-REN (formerly MTA) Institute of Ecological Research, told us that research shows that the rising Danube water temperature is mainly (about 80%) caused by the global increase in air temperatures. According to the ICDPR secretariat, “basin-wide and long-term increasing trends in water temperature are very likely related to climate change. For sure, further research and time series will be needed.” According to the organization, “climate change scenarios for the Danube River Basin predict increases of temperature in general by mid and end of this century, which might have adverse impacts on the temperature of rivers.”

The warming of the Danube affects wildlife as well as power plants’ water supply and production. In Hungary, the water of the Danube is used by the Paks Nuclear Power Plant, Csepel II, Gönyű, Kelenföld, and Százhalombatta plants for cooling.

The Paks NPP, for example, draws 100 cubic metres of water per second from the Danube, which means 8,640,000 cubic metres of water per day.

This would fill roughly 3456 olympic swimming pools – every single day.

Not only does the power plant take water out for colling, but it also pours the same amount of water back in, only heated to 30-35°C. The rising temperature of the Danube presents a serious problem for both the intake and the release of water. The hotter the water, the less efficiently it can cool a plant – which reduces its output. The hot water spilled back can overheat the river and endangers its ecosystem, particularly in low water periods when the water cools down more slowly. Low water periods present a problem for the intake of the water by the plants, too. The Paks plant, for example, was rather close to a water shortage in 2018 that almost caused the plant to be shut down.

Also a growing concern in Austria

According to the Austrian Federal Environment Agency, the annual water demand of industries throughout Austria is 2.2 billion cubic meters, 70 percent of the total demand in the country. 90 percent of the water used by industries is used for cooling, and 60 percent of cooling water demand in Austria is accounted for by metal production and processing. Upper Austria has the most industrial companies in the whole of Austria per federal state, with the locations on the Danube in the steel production, chemicals, mechanical engineering and iron sectors.

One of the oldest and best known is Voestalpine. An average of 60,000 cubic meters of cooling water per hour flows through the pipes for cooling in steel production at the site where the Danube and the mountain river Traun meet. This company is also struggling with an increasingly warm Danube. Just a few years ago, the Danube reached maximum temperatures of 19 to 20 degrees at the site in summer. Now it is already 22 to 23, at least for the last four summers. Like Voest, however, most industries that cool their processes in the country with Danube water are struggling, most of them are in Upper Austria.

There are actually strict regulations on how they are allowed to use the cooling water: at 30 degrees Celsius and no higher, the used water is allowed to end up back in the river. This could prove fatal in the future, as there is less of a temperature difference up to the permitted 30 degrees of cooling water. The result is less production capacity during summer days. Voest has already asked the state of Upper Austria several times in recent years for a special rule, and in the last three years, the company was allowed permit for a maximum temperature of 35 degrees for certain summer days. It is assumed that they will submit an application for an exemption this year as well.

Kurt Eberhardsteiner, Head of the Water Management Department of the City of Linz, says “this can only be a short to medium-term approach, because the Danube is clearly continuing to warm up. On one hand, there is less precipitation in summer and the water flow is tending to decrease. On the other hand, the Traun tributary is also receiving less and less cold water from the Alpine glaciers.” One solution would be the so-called cooling towers, however, says Eberhardsteiner, they can cost several million euros more than a normal cooling water flow.

No uniform regulation

The European Union’s Water Framework Directive aims to achieve and maintain healthy rivers and lakes. The overall aim is to achieve a good chemical and ecological status for surface waters. Surface waters, to be healthy, require that their communities and chemical makeup are mainly unaffected by human activity. The Directive leaves it up to Member States to decide how to best meet these requirements and does not set out a specific EU standard for water temperatures.

In the past, Directive 2006/44/EC on the quality of fresh waters needing protection or improvement in order to support fish life set specific temperature limits: thermal discharges were not allowed to cause the temperature downstream of the point of thermal discharge to exceed 21.5°C for salmonid waters and 28°C for cyprinid waters (such as the Danube). The regulation was repealed by the Water Framework Directive. In Hungary, although it was transposed into national law, the regulation actually never applied to the Danube, as the river, for reasons unknown, was not considered to be a fish water in need of protection by Hungarian legislators.

Hundreds of mussel shells cover the Danube bank below the Paks nuclear power plant on 5 August 2022. Photo: Atlatszo.

The Government Decree 220/2004 sets a fine for heat load above the limits, however, in the absence of limits, this fine is difficult to apply. There is a specific regulation regarding the Paks nuclear power plant: it requires that the difference in the temperature of the discharge water and the receiving water must not exceed 11 °C, or 14 °C if the receiving water temperature is below +4 °C, and that the receiving water temperature shall not exceed 30 °C at any point within 500 meter downstream of the point of discharge.

In Austria, the Danube’s temperature is being measured by regional authorities, the same counts for restrictions for putting cooling water back into the river. For example, in the case of the Donaukanal, an arm of the Danube that flows through Vienna, temperature levels have to be below 26 degrees in 95 percent of measurements. In 98 percent of measurements, its temperature cannot be higher than 27 degrees. In general, the Austrian law puts a cap on the temperature of water that is emitted into rivers at 30 degrees.

This article is a collaboration of Átlátszó and Der Standard journalists. Research and text: Orsolya Fülöp (Átlátszó), Melanie Raidl (Der Standard), Robin Kohrs (Der Standard), Alicia Prager (Der Standard). Data visualisation: Attila Bátorfy, Krisztián Szabó (Átlátszó). Cover photo: Átlátszó. This story was supported by Journalismfund Europe.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!