The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Poets, politicians and saints: Budapest’s changing street names

A third of Budapest’s 8,598 streets and squares have been renamed at least once in their history. A third of those now bear the name of a real or fictitious person, the most popular being Attila József. A look at the reasons for renaming and the issues of political memory it spotlights.

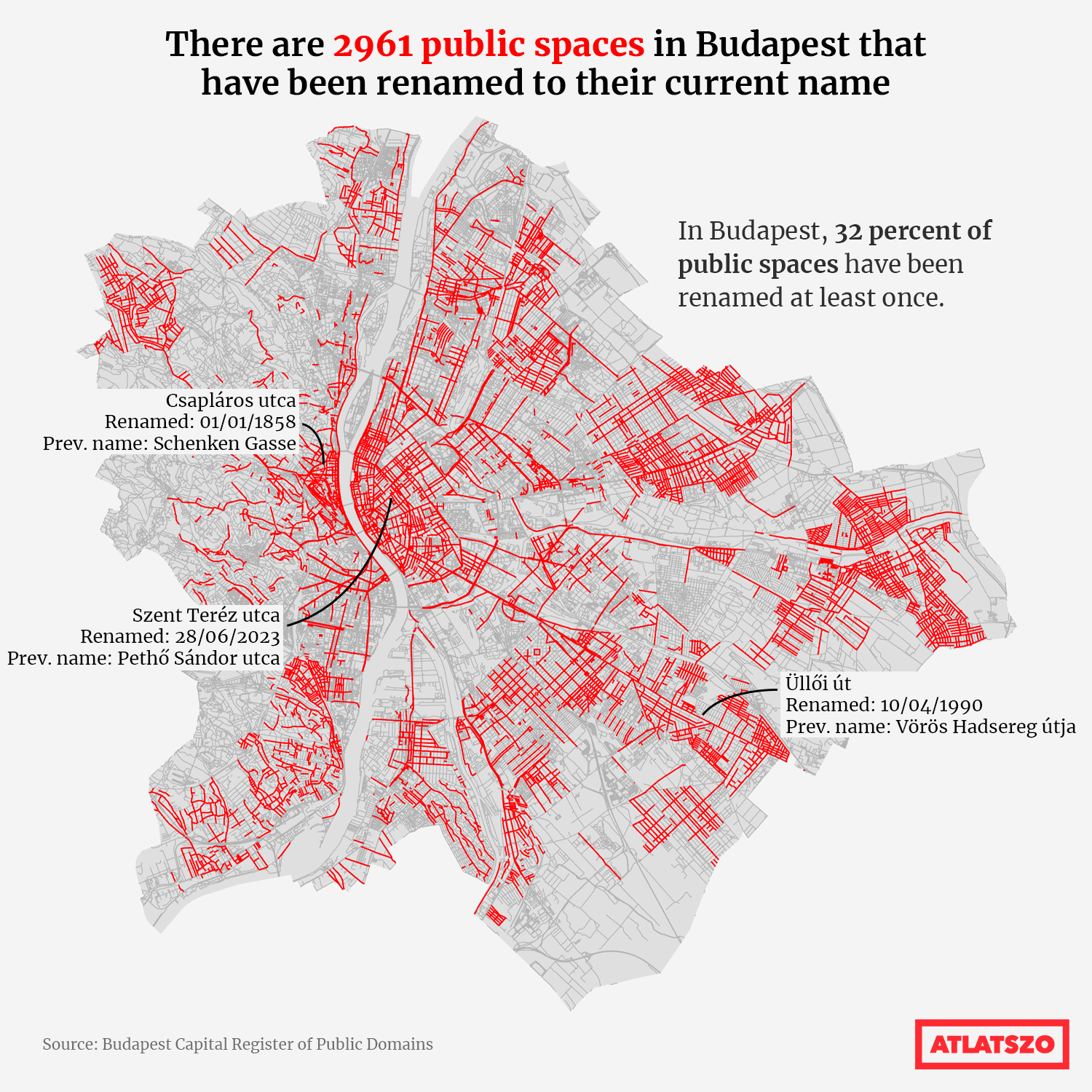

According to Budapest’s register of public domains, one third of public spaces, numbering 2,961, have been renamed. In the database, each current name is listed alongside the previous name, if any. Hovewer, the register does not show the full history for those that have been renamed multiple times.

A good example is the well-known Oktogon intersection, which dates from the early 1870s and adjoins the thoroughfare now known as Andrassy Avenue, itself named in 1886. The Budapest authorities originally gave this public square the name Nyolcszögű, of which Octagon is the ancient Greek translation. It was later known officially as Oktogon from the 1920s until 1936, at which point it was renamed Mussolini Square to coincide with the visit of Italian foreign minister Count Ciano. Within two years Andrássy Avenue was connecting Mussolini Square with Hitler Square, formerly Körönd (which just translates to “Circus” in Hungarian).

Both squares were renamed yet again at the end of the war: the latter reverted to Körönd while the one-time Oktogon became 7 November Square (named after the October Revolution). During the subsequent era of post-war communist leader Rákosi, Andrassy Avenue became Stalin Street, only to be renamed Avenue of Hungarian Youth during the 1956 revolution, and then People’s Republic Avenue in 1957. In 1971, Körönd became “Kodály Körönd”, after a composer who had lived there. The rebranding of Körönd proved to be the only one that endured from the socialist period, with Oktogon and Andrássy Avenue reverting to their original names.

This story, which concerns a single small section of the city, is a good example of how street renaming has worked in Budapest. Each new political regime has tried to show its distance from its predecessor. Right across Hungary, toponyms reflect the fact that the country’s modern history has been full of radical changes.

The best example of all may be Károly Körút (Charles Boulevard). The section of the boulevard between Andrássy and Rákóczi (formerly Kerepesi) Avenues was named after the Károly barracks (former Invalids House, now the Mayor’s Office), only to be changed to Charles IV Boulevard at the coronation of that monarch in 1916.

During Hungary’s short-lived Soviet Republic following the First World War, it became People’s Will Boulevard, then People’s Boulevard, before reverting to Charles Boulevard at the fall of that republic, and then again becoming King Charles Boulevard in 1926. In 1945 it became Somogy Béla Avenue, after a social-democrat newspaper editor, then in 1953 the city council decided simply to rename the thoroughfare after itself, and so it was known as Tanács Körút (Council Boulevard) until 1990.

In central Budapest, the proportion of streets renamed is particularly high in districts V (56%) and I (52%), but only a small proportion of these renamings happened after the fall of the communist regime (7.2% and 2.9% respectively). Outside the city centre, districts XV (54%), XVI (49%), and XVII (46%) have had the most name changes. Those with the most places renamed after people (real or fictional) are VI (69%), VII (64%) and VIII (61%).

From the data, it is clear that renamings have come in bouts. One wave of activity was in the years following the Treaty of Trianon, which settled Hungary’s new borders after WWI. Then the new appellations tended not to honour individuals, but rather Hungarian towns in the territories lost by the treaty.

The next major wave of renaming occurred in 1953. At first glance, this might look to be connected with Stalin’s death and the end of the worst period of his personality cult, but in reality, it had nothing to do with that (we have already seen that Andrassy Avenue bore Stalin’s name until 1956). The reason is rather to be found in an administrative reform of 1950, when seven towns (such as Csepel, Kispest or Újpest) and 16 large villages (such as Békásmegyer, Mátyásföld or Soroksár) were joined to the capital to create the Greater Budapest. The merging of the municipalities led to a proliferation of streets and squares with the same name, creating a wayfinding problem. The resulting renamings were naturally used as an opportunity for commemoration.

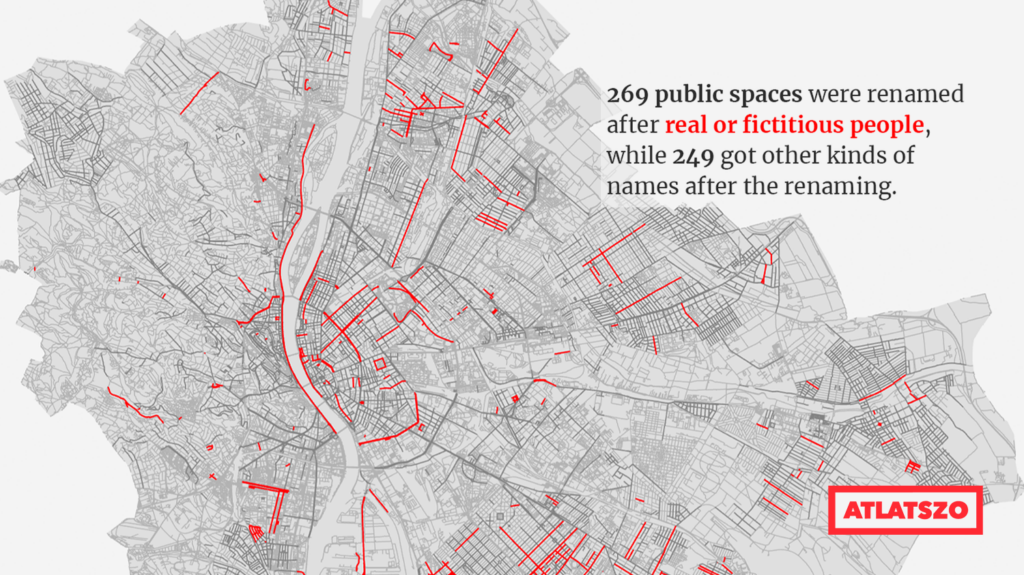

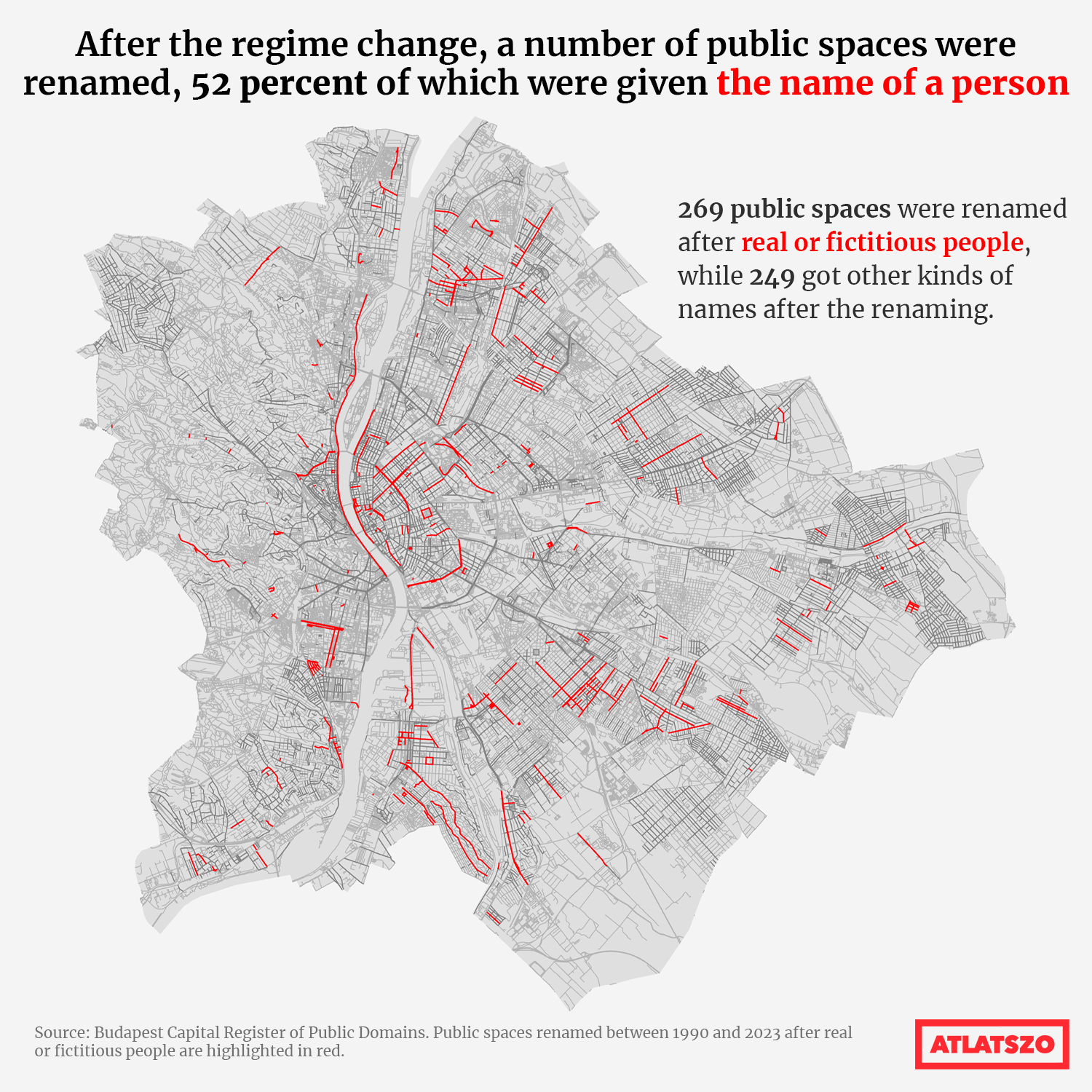

In the post-1990 flurry of renaming, Budapest’s new liberal leadership sought to break with the politics of remembrance and avoid renaming public places after the latest idols. In practice this meant resurrecting historical place names, a consensual policy that did not arouse opposition from the conservative government of the time. That was the last era of mass renaming.

In later years, the expansion of new housing developments helped eliminate the motivation to rename existing places. In 2011, there was indeed a small wave of name changes: Moscow Square became Széll Kálmán Square; Republic Square became Pope John Paul II Square; Roosevelt Square became István Széchenyi Square; Dembinszky Street in District XV became Wysocki Street. But this could be attributed to the excesses of a new mayor, István Tarlós, and the policy quickly ended due to unpopularity.

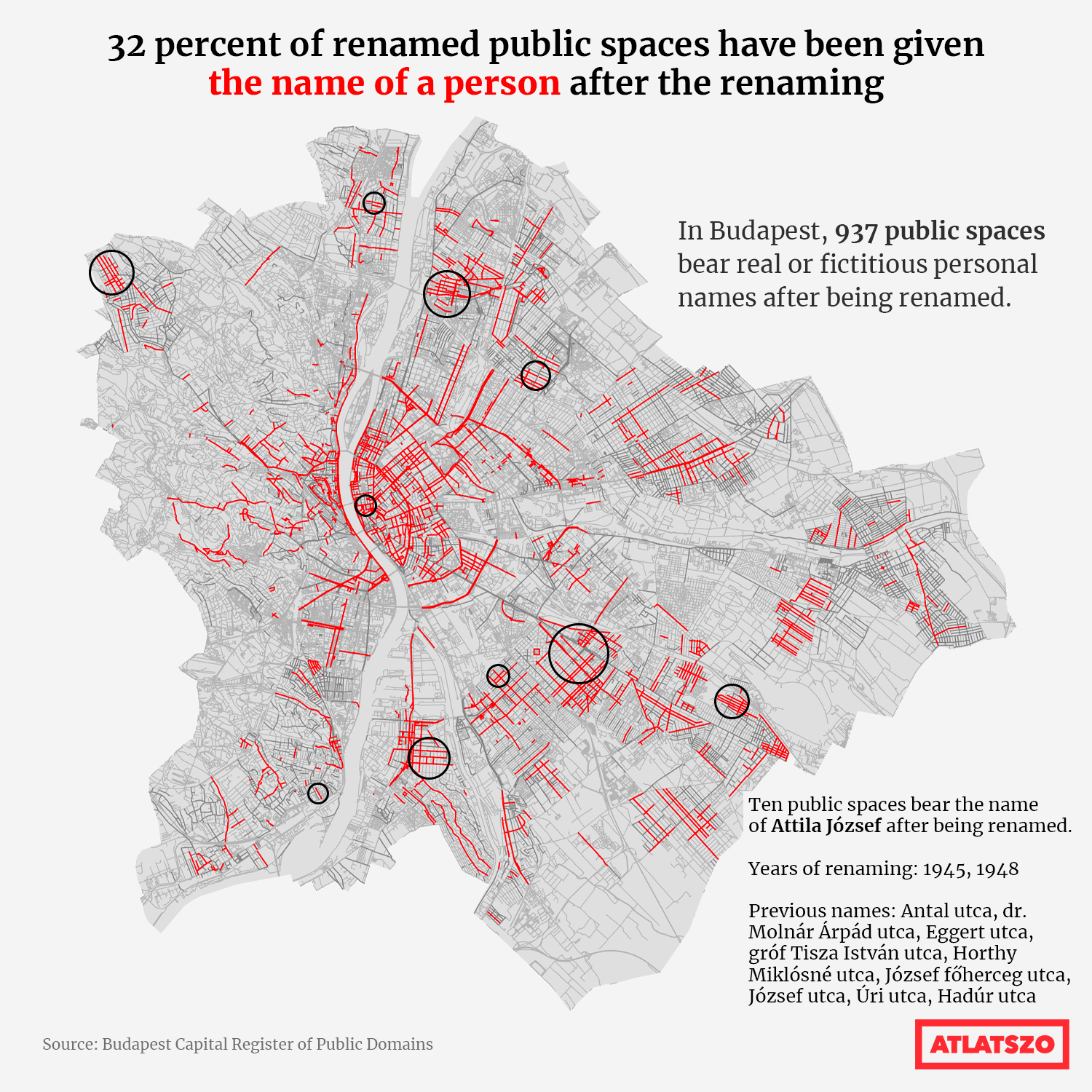

Between 1858 and 2023, 937 public spaces were renamed after people, which represented one third of all the renamings. Ten toponyms were renamed after Attila József between 1945 and 1948, when he was appropriated as Hungary’s proletarian poet by the party-state. Today, 13 places carry Attila József’s name, making him one of the most honoured figures. The first place is occupied by statesman Lajos Kossuth and national poet Sándor Petőfi, with 18 place names each; followed by poet and dramatist Mihály Vörösmarty with 16, statesman Gábor Baross with 14, and poet János Arany with 13.

The naming of public squares has tended to reflect the political values of those in authority, and their conception of commemoration. Since 1990, local districts have had the right to initiate renaming, although in some cases the consent of the city council is required.

During the post-1990 premierships of moderate conservatives József Antall and Péter Boross, district councils renamed places in order to erase the socialist era and its ideology from the capital’s spaces. Thus, Lenin Boulevard became Erzsébet Boulevard, and the People’s Republic Avenue became Andrássy Avenue again. Later, during the second Orbán government, local councils renamed a significant number of streets, 57 of which took the names of people.

The number of renamings also depends to a large extent on the size of the district: the larger the district, the more public spaces it has, the higher the number of renamings. The map below shows the figures by district, aggregated by whether or not the place was renamed for a person, and whether the renaming was before or after the change of regime in 1990. Click on each district to see the year and previous name of the renamed public space.

Since the post-1990 era, when the focus was on changing the former political establishment’s commemorative policy, there has been much less enthusiasm for renaming. This can be seen in their declining frequency. But there has also been a long-term decline in all street naming, due to the increasing densification of the city and the creation of fewer and fewer new public spaces.

The Mapping Diversity project, coordinated by the European Data Journalism Network and OBC Transeuropa, was published in March 2023 and focused on the gender balance of public spaces in European cities. The project featured Budapest, with detailed biographical information on the female namesakes of the capital’s public spaces.

Mapping Diversity is a project that aims to uncover key lessons about the diversity and representation of street names across Europe and to start a conversation about who is missing from the public spaces of our cities. The project examined 145,933 street names in 30 major European cities across 17 countries. More than 90% of the streets carrying personal names were named after white men. So what happened to all of Europe’s other historical figures? The lack of diversity in toponymy says a lot about our past and helps shape Europe’s present and future.

The Budapest place-name register shows that the number of public spaces named after women has always been low compared, the obvious reason being that the most prominent figures in history were mostly men. Despite a decline in street naming in recent years, in 2023 more public spaces were given the names of women (7) than men (4).

Using and extending the data from Mapping Diversity Budapest, we have created a much more detailed database for the Names and Squares project, which we produced in 2022 in collaboration with the Budapest City Archives. We have increased the number of public spaces identified from 2247 to 2591, and created a Mapping Diversity-inspired datasheet for each name. This allows viewers to find out basic information about each public space, including a short biography of the person who gave it their name.

The site already included a description of the streets renamed after the change of regime in 1990. This section has been expanded to include the latest data, from June 2023, thus providing a 33-year overview of the commemoration policy.

Translated by Voxeurop and published in English on the European Data Journalism Network website. The original Hungarian version of this story was written by Krisztián Szabó and András Hont and can be found here.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!