The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

The Organised Crime and Corruption Watch—regional edition no3. Healthcare corruption part I

Corruption in the healthcare sector is unfortunately widespread throughout much of Eastern Europe. In Romania, recent indictments highlight the role of healthcare workers in diverting funds from patient care. In Poland, the state paid tens of millions of euros to an arms dealer for medical equipment that, in part, was never delivered. While in the Czech Republic, public tenders during the pandemic were corruptly steered to businesses selling unlicensed respirators. This is the first part of a two-part series on healthcare corruption.

This collaborative newsletter is based on the research of seven investigative outlet members of The Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project: Investigace.cz (Czech Republic), Bird.bg (Bulgaria), Frontstory.pl (Poland), Rise Project (Romania), Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak – icjk.sk (Slovakia), Átlátszó (Hungary), Context Investigative Reporting Project (Romania). The team will explore an organized crime or corruption topic for each edition and showcase the most relevant facts.

Mass corruption in the Romanian healthcare system

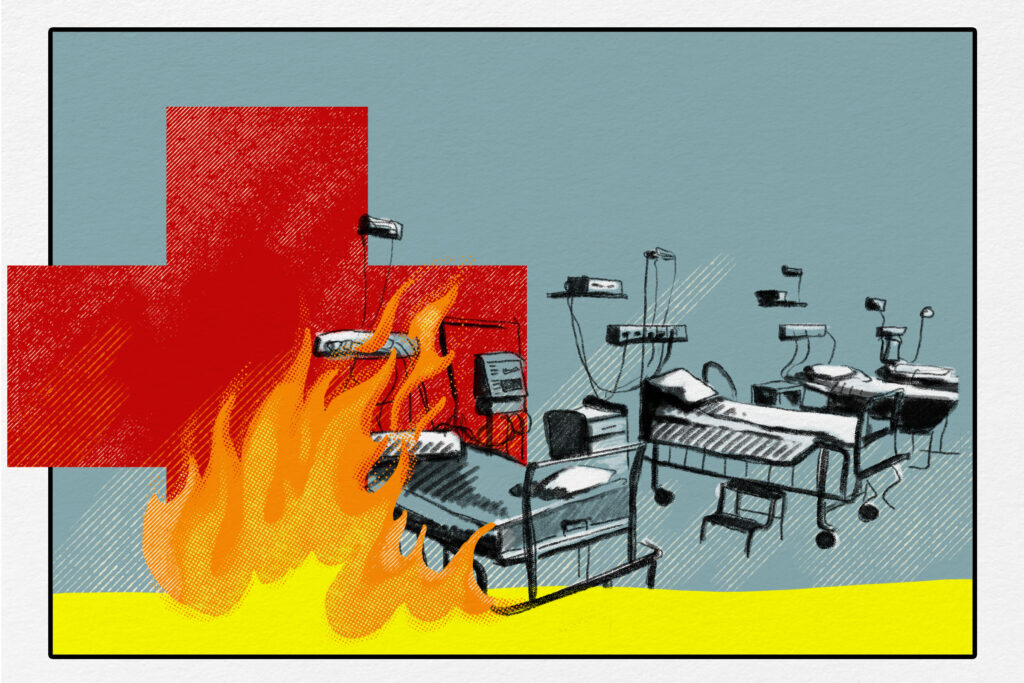

In 2010, six babies died in a hospital fire in Bucharest. More than ten years later, the same hospital is still functioning without a fire safety permit. Unfortunately, this is not an isolated case; it’s just one of the many public Romanian hospitals endangering the lives of their patients because they have never been modernized and lack proper systems to keep their patients safe.

These deficiencies were revealed during the Covid-19 pandemic as the Romanian medical infrastructure was heavily used. In 2020 and 2021 alone, a dozen hospitals caught fire in Romania, and more than 30 people died.

A 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) report states that Romania has significantly increased its health spending but remains the EU country with the second lowest health expenditure, both on a per capita basis and as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Even the Ministry of Health said that the public health infrastructure needs to improve and that recent investments were still insufficient to bring it up to proper performance standards.

However, corruption is a big threat to Romanian healthcare system development. Money spent for the improvement of the infrastructure is often landing in the pockets of companies with political connections. This hinders medical system improvements because hospital needs are often put in second place.

In 2022, the National Anti-Corruption Division indicted more than 50 people working in the Romanian healthcare system. Amongst these are one manager, seven doctors, and three hospital directors.

The Romanian press has also investigated inefficiency and corruption in healthcare spending. In 2016, Rise Project published a story about a Hyperbaric Chamber, equipment used for burn care, which cost more than half a million euros and proved inefficient and even dangerous for the patients. The company that received the money was owned by the business associate of a former mayor and Romanian senator, Sorin Oprescu.

The pharma lobby corruption in Poland

Shortfalls in hospital budgets, staffing problems in institutions, and difficult access to specialists are the most common sources of corruption in Polish health care. Underfunding of the system also translates into low salaries, which in turn pushes doctors into the private sphere or to work abroad. Hospitals are seeing long waiting lines for diagnostics and treatment, according to a European Commission report on corruption in health care.

Another example of corruption in the Polish healthcare system is the January 2022, Frontstory.pl story revealing trafficking fake vaccination certificates against Covid-19, with the involvement of corrupt employees of medical institutions.

Polish society, for the most part, believes that a bribe given to a doctor is corruption, but using a network of private and professional contacts to bypass the queue to see a doctor is common. The result? In July 2022, an indictment against the former head of the palliative care department of a hospital in the small town of Chodzież was filed in court. The doctor was supposed to accept or extend the stay of patients in his ward in exchange for bribes from families – from several hundred to several thousand zlotys. He did this even though the patients did not require extended stays.

The Commission’s report shows public tender irregularities are also a problem. Tender specifications are sometimes drawn up by doctors, who in some cases, have to ask industry representatives for help. And these can prepare the specifications in such detail that only a particular company can win the tender. In December 2022, moments after accepting a bribe, the director of an outpatient clinic in the small town of Witkow was detained, according to the Central Anticorruption Bureau; in exchange for a bribe, he was alleged to have crafted a tender for the supply of medical equipment.

One area of health care susceptible to corruption is the interface between the state and the pharmaceutical lobby. As of January 2023, 911 corruption charges had been handed down to 12 people, including a pharmaceutical company representative, pharmacists, and doctors from medical facilities in and around Warsaw. The pharmaceutical salesman allegedly arranged with the doctors to issue prescriptions for the drugs he promoted and rewarded them with money.

This is not limited to local hospitals and doctors. A 2019 official report shows that the Polish Ministry of Health is “particularly vulnerable” to lobbying, informal pressures, and corrupt proposals when dealing with external actors, mainly from the pharmaceutical industry.

Millions of euros for ventilators provided by the arms dealer

While the world was battling the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the Polish health ministry signed a series of controversial contracts for medical equipment supplies. One involved the purchase of worthless protective masks for €1.1 million from the company of a friend of the minister himself. The Polish state also purchased ventilators worth €44.5 million (some of which were undelivered) from the company of an arms dealer who first disappeared under mysterious circumstances and was later found dead in Albania. According to recent information, no one has been charged in the investigation into the “mask affair,” and the investigation into the ventilators was dropped in 2021.

According to the Central Anti-Corruption Bureau’s report on the implementation of the Government Anti-Corruption Program for 2018-2020, healthcare was among the spheres most at risk of corruption. What has been done so far to reduce the threat? An e-learning course on ethics, anti-corruption, and conflict of interest was organized for ministry employees. An “anonymous self-assessment of the culture of integrity” at the ministry was also conducted. The results of the self-assessment have yet to be discovered.

The man behind corrupt healthcare public tenders

There is one prominent figure and a former politician connecting two cases of corruption in the Czech healthcare sector – Marek Šnajdr. One of the cases is known as the Dozimetr case, which became known after a police raid of the Prague City Hall, the General Health Insurance Company (VZP), and more than ten other places, which took place last June. According to investigators, public servants accepted bribes to manipulate public tenders. Marek Šnajdr, a former Czech member of parliament and influential figure behind the scenes in the healthcare sector, was accused this April of bribery. He paid almost €8,500 to secure a favorable outcome on a €4.3 million IT contract awarded by VZP. The IT company hired was unable to deliver and should have paid a steep penalty. Šnajdr’s bribe to VZP was meant to secure that the company would not pay the penalty and only cancel the contract with no repercussions. Marek Šnajdr denies the charges, but he’s been recently interrogated by the police.

Marek Šnajdr is also accused in the Bulovka case, where he was alleged to have manipulated contracts at the Bulovka hospital. In addition to Šnajdr, the indictment also covers the former director of the Bulovka hospital and other people. The accused supposedly manipulated the public tenders so the contracts would fall to predetermined companies. The same actors are also under investigation in the case of another hospital’s corruption – Na Františku Hospital, in which its former director was charged. The case involved as many as two dozen defendants. The whole case started in 2018 when the police raided the two hospitals. One of the actors in both cases, businessman Tomáš Horáček, began cooperating with the police, which allowed them to uncover the extent of the corruption schemes. All three cases are still ongoing.

Covid fraud schemes in the Czech Republic

The Czech municipalities spend more than €8,4 million on protective equipment, with one particular company selling one respirator for more than €8 per piece.

In the spring of 2020, the government failed to supply protective facial wear to the municipalities, even though politicians at the time insisted they had the situation under control. So companies completely unrelated to healthcare but with good contacts in China – started selling respirators, including a producer of cloth nappies, a seller of shotguns and fireworks, and a solar power plant builder. Why? Because it was worth it as the state gladly paid millions of Czech crowns for the merchandise. The companies that actually produce healthcare equipment were in the minority.

However, there was one condition under which the respirators were allowed to be sold in the Czech Republic – they had to have an EU-approved certificate, “CE”, which means they are safe to use. But this didn’t stop the sale of respirators with either fake or different certificates or none at all.

One of the companies that decided to use this opportunity was a marketing and PR company called Black Consulting. The company sold €8 respirators to the state and received over one million euros. Their respirators did have a stamp of a company that does grant certificates but for different products, not respirators. The documentation that was a part of the public contract doesn’t contain anything that would suggest Black Consulting had any certification whatsoever.

David Snášel, the owner of Black Consulting, gave an interview to Investigace.cz in which he said that he once received a call from a friend who offered him thirty thousand respirators for his employees. After the phone call, Snášel realized that the respirators would be good business, as regional governors complained about the lack of them. He wrote up a proposal and sent it to the municipalities, and within an hour, the first county governor called, and business took off.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!