The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

Road to ruins: once world-famous Transylvanian spa in tragic decay after botched privatisation

After a drawn-out courtroom battle that saw thirty-five accused, no one really knows who is truly responsible for the demise of the Hercules Baths. The once-towering host to decadence has declined into little more than a set of rotting walls – a decay caused, in part, by the passage of time and aggravated by privatization. A morbid disaster tourism still draws some to the site, but their visits only briefly interrupt the solitude of the stray dogs and flies that otherwise occupy the building’s carcass. This joint article by the RISE Project and Átlátszó is supported by Journalismfund Europe.

Vast forests sprawl across the rolling hills of the Cerna Valley in the southwest of Romania, around 400 kilometres from Bucharest. The crumbling Hercules Baths – Băile Herculane to the locals – are nestled at the bottom.

The architecture may bear the marks of both the Austrian Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, but the valley’s hot springs were discovered eras before by the Romans, who built a temple and an altar for Hercules and baths, most likely under Emperor Trajan. The baths didn’t survive the mass migrations, and it was only after a Viennese doctor rediscovered the healing powers of the water in the summer of 1733 that the valley became popular once again. Thus –baroque palaces.

When Károly Tatártzy took over the lease of the spa in 1854, it was undistinguished from the other provincial spas in the country – all built by Francis I, all touched up by subsequent kings after the Turkish era, all used mainly as military baths. The Hercules Baths were owned by the Hungary State Treasury and administered under military command until 1873.

Tatártzy enlisted renowned Viennese architect Wilhelm Doderer, a professor at the Vienna University of Technology at the time, to design the baths. There were ambitions to build the country’s nicest spa in the Hercules Baths, but the remote location and lack of resources saw them fall just short.

But, even with the imperfections, the Hercules Baths were one of the Monarchy’s most popular spas, and by all accounts, an impressive site.

The opulence attracted high society – Queen Elizabeth in 1887, and the leaders of the monarchy, Romania, and Serbia for a summit on September 27, 1896. By this point, the baths grew to an imposing size with 681 rooms.

Pride before the fall

The baths became Romanian property after World War One, where they had grandiose plans for a five-storey luxury hotel with a hundred rooms, complete with a restaurant, reading room, and state-of-the-art entertainment facilities.

The plans were there to grow; the reality was regression.

In 2001, the government – then a Social Democratic Party (PSD) administration – decided to sell the complex to companies that had no spa tourism experience and all the right political connections. The former mattered little, the latter mattered very much.

The buyer company was subordinated to two members of parliament from the ruling party: PSD MP Iosif Armaș (2000-2004), who was the sole owner of the company, and PSD Senator Doru Ioan Tărăcilă (1990-2008), who was a minority shareholder.

As luck would have it, a whole series of historical monuments ended up in the hands of the PSD officials. Fortuitous for them, less so for Romanian history – they made no effort to preserve or renovate anything, and the monuments fell into ruin. By 2008, their company was indebted past the point of saving, and one by one, like the Oprahs of ill-gotten Romanian monuments, the officials sold off their assets to private and legal entities.

But investigations by the Romanian Organised Crime and Counter-Terrorism Department (DIICOT) found that this distribution of assets was, in fact, a concerted embezzlement operation disguised as various legal transactions.

After a protracted investigation that lasted years, the case now has thirty-five defendants, with Armaș at the head. Tărăcilă is not among the defendants.

The privatisation of the tourist assets of Hercules Baths has been modelled on the governmental affairs of a banana republic. The Ministry of Tourism, led by PSD member Dan-Matei Agathon (left), sold it, while PSD MP Iosif Armaș’s company (right) bought it. The Tourism Ministry now claims that the 2001 privatisation contract has since been lost. PHOTO: Mihai Vasilică / Mediafax.

If the investigation’s goal was to bring justice to the Hercules Baths, the target has been badly missed thus far. There would be interest and tourists are still attracted – but the company’s properties are now listed on their title deeds as being involved in criminal activities, and any sale, purchase, or renovation is a risky investment.

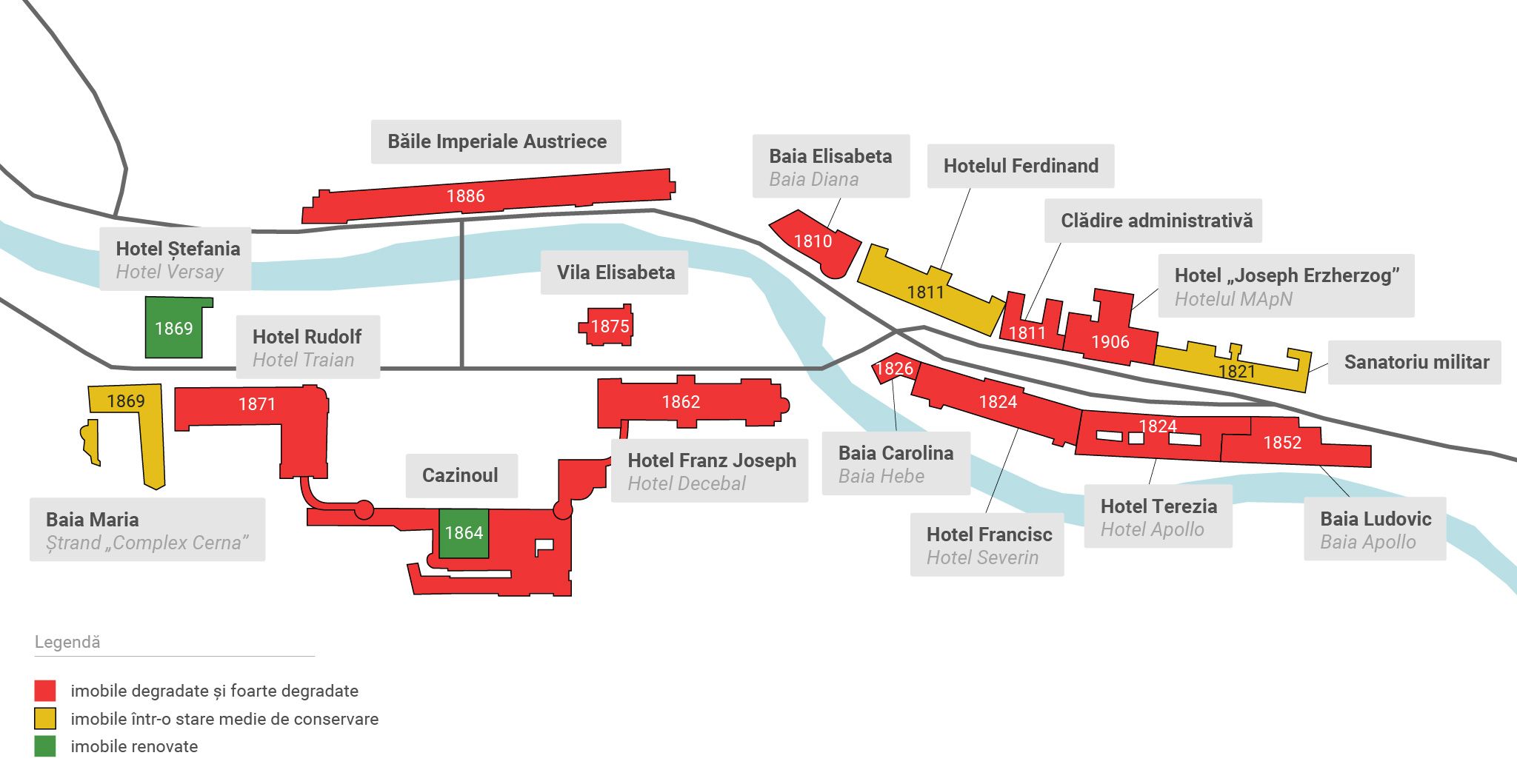

And although some of the buildings are owned by the state or municipality, these properties have not fared much better due to the lack of resources.

Translated by Vanda Mayer. Written by Eszter Katus (Átlátszó) and Ionut Stanescu (Riseproject). Photos by Sergiu Brega. More detailed story in Romanian on the Riseproject website and in Hungarian on the Átlátszó website. This story was produced with the support of Journalismfund Europe. Archival Hungarian material for the article was provided by the Arcanum database. Cover photo: The iconic Hercules Baths, the Austro-Hungarian imperial spa.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!