The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

State agencies hide monitoring data gathered on groundwater in Hungary

The fact that nothing is known about the state of groundwater is a sad example of the deplorable state of environmental protection in Hungary. Yet on this year’s World Water Day, the UN has set itself the goal of “Groundwater – making the invisible visible”. However, national data on this issue have long been invisible in the National Environmental Information System, because the site is “under construction”. We asked for when the search engine would be available, but this was not even revealed. The concealment of information may be linked to pollution from certain industrial plants, but also to the disastrous situation of the domestic water utility system.

„There are activities that may pose a threat to groundwater and geological medium quality if performed not in accordance with the requirements and the relating regulations. Using the document queries available on the OKIR website, you can learn as what they are, whether such activities are carried out in the vicinity of your residence or in any arbitrary point in Hungary, and also what kind of pollutants are used in carrying out these activities,” says the National Environmental Information System (OKIR) website.

However, the text states the untruth: no data has been available on the website for at least a year. The Groundwater and subsoil protection module has been “under development” for a long time. Thus, no information is available on the results of water tests, nor on activities and pollutants that threaten our waters.

The OKIR website is hosted by the Ministry of Agriculture, so we sent them questions about the availability of the environmental information system. We wanted to know who was developing the website, how much it would cost, when it would be available and when the groundwater data would be available.

However, the Ministry of Agriculture only replied that the IT improvements to the system are “ongoing”. In other words, despite the call on the occasion of this year’s World Water Day to “make the invisible visible” in order to protect groundwater, information on groundwater in Hungary remains invisible.

This is not the first time that we have been unable to access information due to website upgrades. In May 2020, during the first wave of the crown virus, the National Employment Service’s website was redesigned. Just when everyone was wondering how many people had been made redundant because of the restrictions, how the number of people in employment had changed compared to previous years. While some recent data was available on the new website, the archive has almost completely disappeared. The changeover took place without the old interface being available at all, and the old data had not yet been uploaded to the new site.

They work with toxic substances, yet they hide monitoring data

But it is no easier to get water test data from water authorities. Átlátszó previously reported that the Budapest Disaster Management Directorate, which is responsible for water permits and inspections at the Samsung battery factory in Göd, does not release test data from monitoring wells in the industrial area. In fact, it is claimed that for “objective reasons” reported by the operator, no water tests have been carried out for two years – even though the water permit issued by the authority requires annual monitoring. The refusal to disclose the data is also worrying because, as we wrote in another article, toxic sludge leaked from the Samsung factory’s wastewater treatment plant, for which the company was fined one million forints.

In early January, we turned to the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (NAIH) because of the refusal to provide data. However, the NAIH is still investigating the matter. In any case, it is alarming that the disclosure of water monitoring data from a factory that uses thousands of tonnes of toxic substances should be so hampered.

“Civil courage” for data retrieval

Domestic groundwater can be polluted not only by dangerous industrial plants, but also by leaking water pipes due to ageing water networks and frequent pipe bursts. If information on the extent of pollution is not available, data on the technical state of the domestic water system is finally available thanks to the persistence of civilians.

In December, we wrote about how a coalition of NGOs, trade unions and municipalities had come together to tackle problems in the domestic water utility sector and water supply. Members of the Water Coalition are seeking solutions to domestic water supply problems and are calling for government intervention to finance the renewal of water utility systems. In March this year they launched a series of national programmes called Water Week.

The Water Coalition has conducted a professional study, which includes thematic maps, provides a wealth of information on the state of water utilities in Hungary. The study first clarifies the finding – quoted in our previous article – that 86% of the domestic drinking water supply system can be classified as at risk.

However, this rating, published by the Hungarian Energy and Public Utility Regulatory Office (MEKH), only applies to the material of the pipe system: they have determined this ratio on the basis of the amount of PVC and asbestos-cement pipes still in use and classified as risky.

In fact, a comprehensive health assessment and risk analysis of drinking water supply networks in Hungary has not yet been completed. In addition to the material of the pipelines, a lot of other data needs to be collected and aggregated in order to get a comprehensive picture of the technical condition of the water utility system and the corresponding reconstruction tasks.

The Water Coalition wanted to fill this missing gap, and to do so, it requested data for 2020 from water utilities through a public interest request. Of the 38 operators of drinking water supply systems, 30 have provided the data. The five state-owned operators refused to provide the data in a letter with uniform content and format.

Andrea Homoki, community organiser of the Civil College Foundation and member of the Water Coalition, said that they have filed a complaint with the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information. Subsequently, several service providers indicated that they would comply with the data request within 45 days.

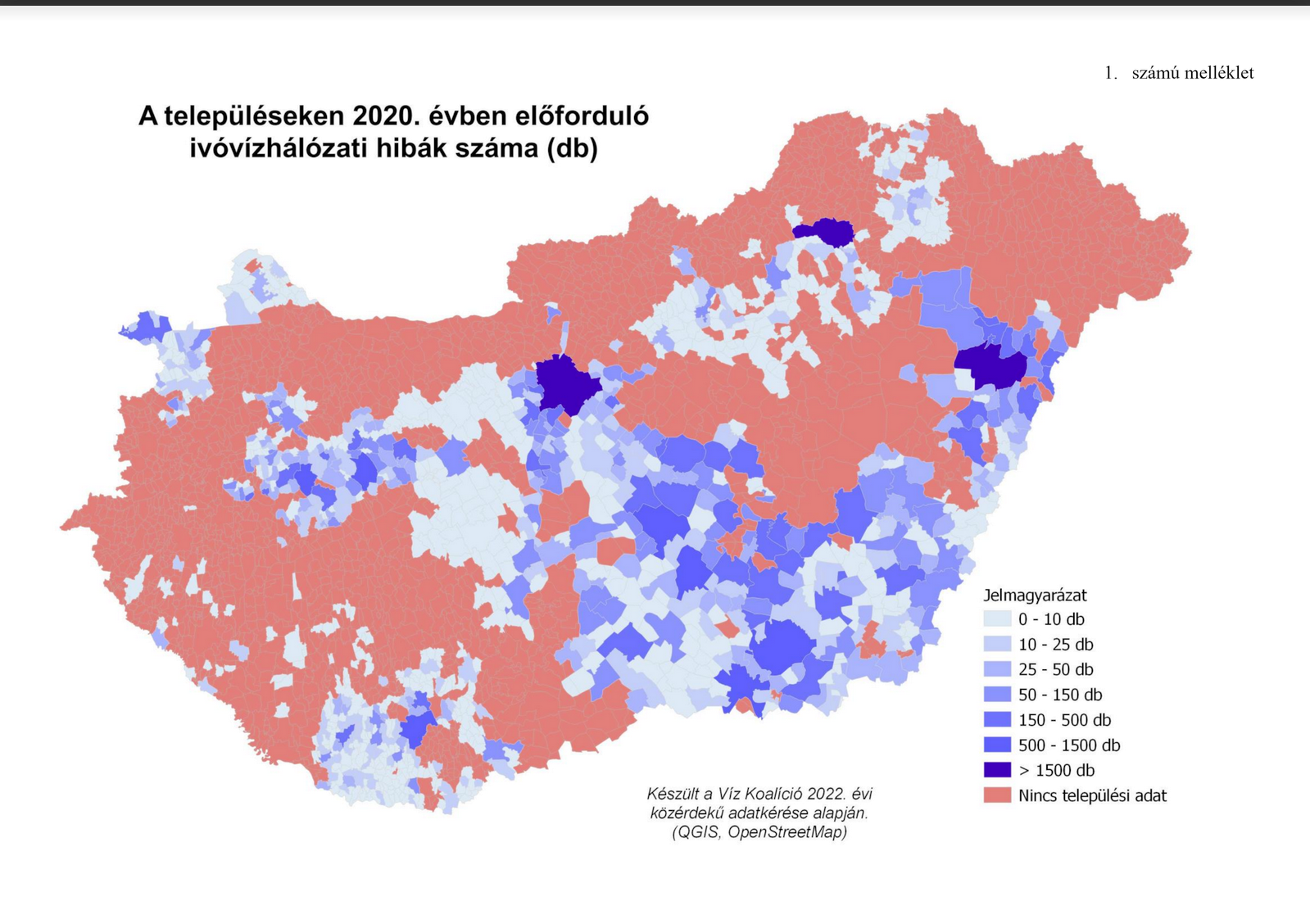

The study, based on data provided by thirty water utilities, presents brief analyses and thematic maps showing some of the technical state of the drinking water network: the number of breakdowns for 2020, the length of pipes rehabilitated, and the quantities of water recorded as network and sales losses.

Based on a summary of the available data, the national average fault density is 0.91 faults per kilometre. The average length of the renewal cycle of the lines is 262 years, the average network loss is 20%, while the average loss on sale is 21.91%.

Of course, the survey could not be complete due to missing data. However, according to Csaba Kun, the study’s author, the condition of water utilities in areas where no data were available may be similar. He also stressed that it is not possible to draw far-reaching conclusions from one year’s data. However, he hoped that the data now published in the study would lead to responsible action to ensure the safety of water services.

Average number of faults in the drinking water network (burst pipes, cracks): 42 technical faults per municipality. In Budapest there were 4482 technical faults.

Andrea Homoki of the Water Coalition said that when the missing data from the public utilities arrive, they will be added to the 2020 survey. And in the following years, the request for data on the technical condition of water supply systems will be repeated in order to monitor the process of deterioration and improvement. In addition, they will continue their Clean Water in our Glasses campaign, which has set out concrete proposals and expectations to improve water services and ensure public access.

Written and translated by Zsuzsa Bodnár. The original, Hungarian version of this article is available here.

Hungary. What do you know about Hungary? from atlatszo.hu on Vimeo.

Share:

Your support matters. Your donation helps us to uncover the truth.

- PayPal

- Bank transfer

- Patreon

- Benevity

Support our work with a PayPal donation to the Átlátszónet Foundation! Thank you.

Support our work by bank transfer to the account of the Átlátszónet Foundation. Please add in the comments: “Donation”

Beneficiary: Átlátszónet Alapítvány, bank name and address: Raiffeisen Bank, H-1054 Budapest, Akadémia utca 6.

EUR: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0040 0002

USD: IBAN HU36 1201 1265 0142 5189 0050 0009

HUF: IBAN HU78 1201 1265 0142 5189 0030 0005

SWIFT: UBRTHUHB

Be a follower on Patreon

Support us on Benevity!