The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

New layers of broker scandal revealed

New layers to the scandal of Hungary’s largest white-collar criminal scheme to date, are revealed as investigations continue. Atlatszo.hu has found that one of the companies at the center of what is known as the ‘broker scandal’ has an even more suspicious background than previously thought – one of its Liechtenstein-based owners used the stocks of a phantom company to become the majority owner of the embattled investment firm.

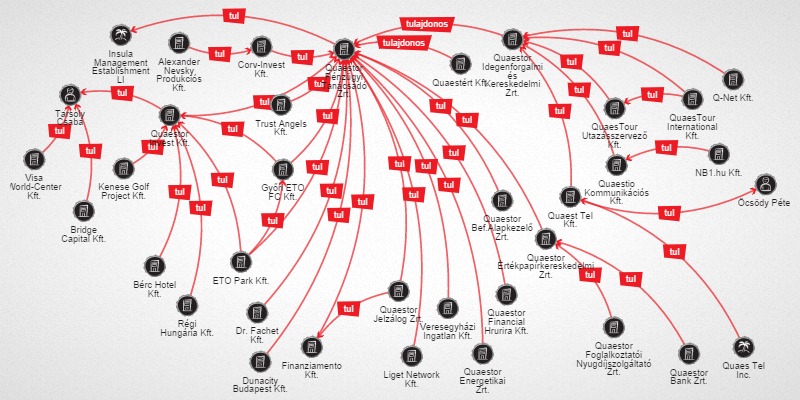

The Quaestor group is at the center of a massive scandal that continues to rock Hungarian investment companies and brokerages today.

The company has allegedly robbed people of several fortunes over many years, with its leaders now facing criminal charges. But Atlatszo.hu has found that questionable practices related to the firm are by no means a recent development. In 1999, the firm came under the ownership of a Liechtenstein-based body, which financed the deal using the stocks of a phantom company.

Insula Management Establishment LI declared in 1999 its intent to purchase 1 million 882 thousand shares in Quaestor Zrt, a company that at the time had registered capital of HUF 118 million (€386,000) and was owned by someone seriously implicated in the current scandal, Csaba Tarsoly and his wife.

Insula made a commitment to implement a 400% capital increase. The Vaduz company paid for the deal with the shares of Quaestcom Inc., an Iowa-based company, even more enigmatic than the Lichtenstein buyer.

Although the transaction involves a total of $30 million, we could find no trace of Quaestcom’s operations over the past decade.

The Iowa firm is owned by Peter Öcsödy. Records show that he has had plenty of dealings with the Quaestor group over the years, as evidenced by the similarities in the company names. However, our efforts to contact him have failed, the numbers for his registered businesses are offline, and even his friends and associates aren’t able to get a hold of him.

Hungarian authorities have at least picked up on the notion that there might be something suspicious in the deal between Quaestor and Insula. In 2003 The financial market supervisory agency questioned one of the Quaestor arms, saying it couldn’t confirm details about Quaestcom’s operations, which is problematic since that company’s shares represent a major chunk of the firm’s wealth. At the time, Quaestor reassured the regulator that Quaestcom is not an offshore firm but a genuine market participant. At the time Quaestor also stated that it had sold its package of Quaestcom shares by that point.

The confusion regarding the matter is extensive. As Atlatszo.hu was told by investigators, Hungary requested international legal aid to determine who the actual owner of the Quaestor group is, while our efforts to reach Insula in Vaduz have failed.

Hungarian authorities are now making extensive efforts to unravel the ownership of Quaestor and determine who can ultimately be held accountable for the damages they caused by selling junk bonds. There is a good chance that the company group’s wealth won’t be adequate to compensate, given that its 2013 balance shows rollover debts of HUF 150 billion (€490 million).