The https://english.atlatszo.hu use cookies to track and profile customers such as action tags and pixel tracking on our website to assist our marketing. On our website we use technical, analytical, marketing and preference cookies. These are necessary for our site to work properly and to give us inforamation about how our site is used. See Cookies Policy

The struggles of Hungarian nationalists in northern Serbia

Ethnic Hungarian groups in northern Serbia are struggling to survive following their defeat in the 2014 election, and in spite of strong backing from the radical drive that is thriving in Hungary. Atlatszo.hu explored the many factors which make them vulnerable, including local demography as well as the dominant influence of the Budapest-based moderate right wing that has become the go-to party for ethnic Hungarians, even though the messages are coming from a different country.

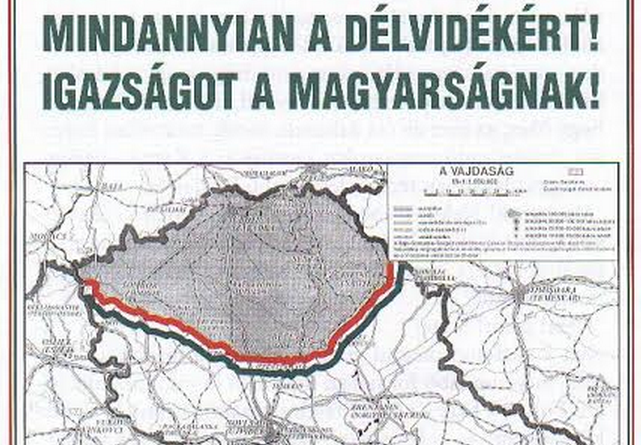

Nationalists in Vojvodina (or Vajdasag in Hungarian) find themselves in a difficult position in 2014, both in terms of the evolution of the local demography as well as the development of the political landscape. These Hungarian nationalists live and operate south of the borders which were established following the end of World War I, set out in a treaty which drastically reduced Hungary’s territory on all sides, creating large ethnic minorities in neighboring countries, including what is today Serbia.

This historic heritage has, of course, led to tensions which have culminated in local hostilities, accusations of nationalist sentiment from the host countries’ authorities, and sometimes outright diplomatic conflict.

Ever since the dissolution of Yugoslavia, there has been almost continued political turmoil with countless elections. These past decades have produced political parties with various, and often flexible, affiliations. With the election victory of the conservative Fidesz party in 2010 in Hungary and its drive to integrate the “nation” that reaches beyond Hungary’s actual borders, it found an ally in the association of Vajdasag Hungarian (VMSZ). This is the strongest party representing ethnic Hungarians in Serbia. While in the past VMSZ followed an “equal distance” policy in relation to Hungarian party politics, it committed itself to Fidesz in the political cycle which started in 2010.

This is one of the reasons locals believe VMSZ dominated in the March 16 national elections, crushing all other ethnic Hungarian groups, radicals included. Most notably, the radical Jobbik could have predicted far better results given its prominence as a backer of Hungarian nationalists in Serbia, as in other neighboring countries, as well as its success within Hungary.

However, VMSZ could not be beaten with Fidesz in its corner. The Hungarian governing party also benefited from backing the right horse. Fidesz gained the majority of Vajdasag votes in the Hungarian general elections in 2014, which for the first time included the votes of ethnic nationals, following the introduction of dual citizenship and voting rights given to Hungarians living abroad after the election victory in 2010

Those in Vajdasag report that VMSZ wasn’t above using dirty methods to achieve victory, including keeping “lists” of party affiliations and political leanings. In certain places, the party’s influence was so strong that getting or holding a job entailed being “in” with the party. Radicals complained that they were sidelined by the media, which also labeled them as Hungarian fascists, and at the same time they were subjected to harassment from the police.

The nationalists have lost a large chunk of their potential voter base for simple demographic reasons. Between 1991 and 2001 alone, the local Hungarian population reduced by around 100,000, from 340,000, mainly due emigration and low birth rates. Young people in particular had left as refugees and more recently simply emigrating to the EU, thanks to gaining dual Hungarian citizenship and easier access to the European Union. As such the radicals did not have the disgruntled youth to rely upon; they had lost their go-to base.

Grasping for a foothold

Various nationalist groups within Hungary had, and still have, a vision of revising the Trianon borders. Hungary’s radical Jobbik has made the most tangible efforts to establish a foothold in the ethnic Hungarian communities in neighboring countries. In addition to fostering closer relations in the area, it went so far as to attempt opening an office in Vajdasag. This was initially prevented by VMSZ, given Jobbik’s track record and the that idea that a Hungarian political party comes into a neighboring country, stirs up tensions, then leaves. In fact, an office was opened although it was almost instantly shut down. Jobbik MP István Szávay has stated that he has not given up on local representation, and would maintain the facilities from his own funds, so there could be no allegations of financing coming from a foreign political party.

Despite Jobbik gaining significant ground in the European Parliamentary elections in Hungary, its plans for building a base in Serbia are proving to be problematic. Although the local branch cites a growing headcount, it claims it is being suppressed by VMSZ and its alliance with the governing power in Budapest. They also claim that they are neglected locally by the media, sometimes in a discriminatory fashion.

Nevertheless, Jobbik is determined to continue with its tried-and-tested community building methods in Serbia, organizing various festivals and gatherings, even though these efforts occasionally have to be relocated because they are frowned upon by the authorities. The activities normally include recreating rituals which are part of ancient Hungarian lore, learning history and culture, as well as excursions to historic monuments.

Riding the sentiment

Radical groups have the best opportunity to organize themselves in areas that are poor and where there also likely to have been conflicts between locals and the ethnic Roma minority. It is common in Vajdasag to publish Roma or gypsy jokes, blatantly and without any regard for political correctness. This attitude was especially prevalent in the media towards petty crime, which in general was attributed to the Roma. Tensions escalated to the extent that media commentary was calling for legal changes to allow gun use against criminals, as self defence and to help protect family safety and assets. The local government also became a target of criticism for distributing targeted aid to impoverished Roma groups.

While there was no statistical evidence, locals attributed an increase in petty crime to Roma and since the police refused to take more resolute measures, they decided to take matters into their own hands. Several Hungarians formed volunteer police or neighborhood watch groups, something that is an established form of local enforcement in many countries, but is not part of the legal framework in Serbia. In fact, given that the Balkan wars have left firearms in many households, vigilantism could easily become widespread and lethal.

Although they lacked any legal justification, it became common for “spontaneously formed” groups to go on walks at night, obviously trying to intimidate potential criminals. Paradoxically, these same groups were also highly appealing to ‘anti-social’ elements from the Hungarian community, and this eventually led to the locals turning against the vigilante groups.

In effect, areas where there is crime and poverty aggravated by ethnic tensions still provide radical groups with the best potential base for attracting support. Such social problems could also be used as rallying points for spreading panic, especially through the effective use of social media.